by Conrad & Claudia.

Today, we visited Little Seed Gardens on a hot, heavy midday with hazy, overcast skies. Little Seed is located on the west bank of the Stony Kill, and that stream unites with Kinderhook Creek in the northeast corner of the farm. They grow organic veggies and raise Randall Cattle (a rare land race from VT).

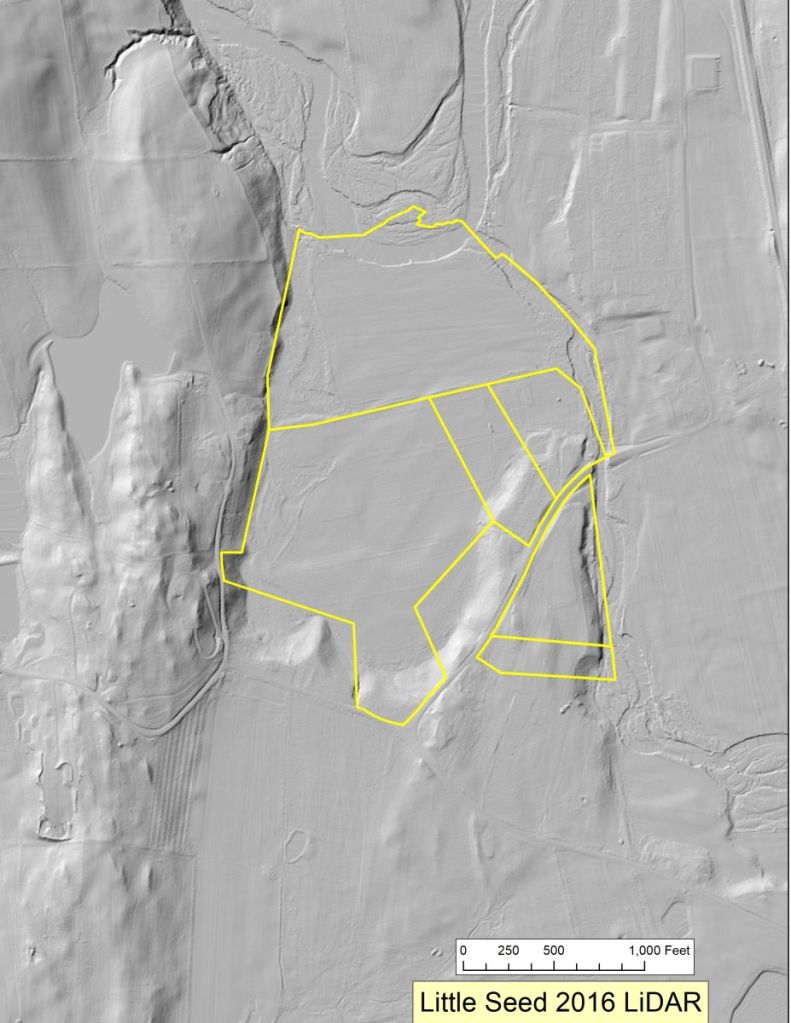

This LiDAR image (LiDAR is way of mapping the detailed, small-scale topography from aerial imagery) suggest that almost the entire farm is in the historical floodplain of Kinderhook Creek.

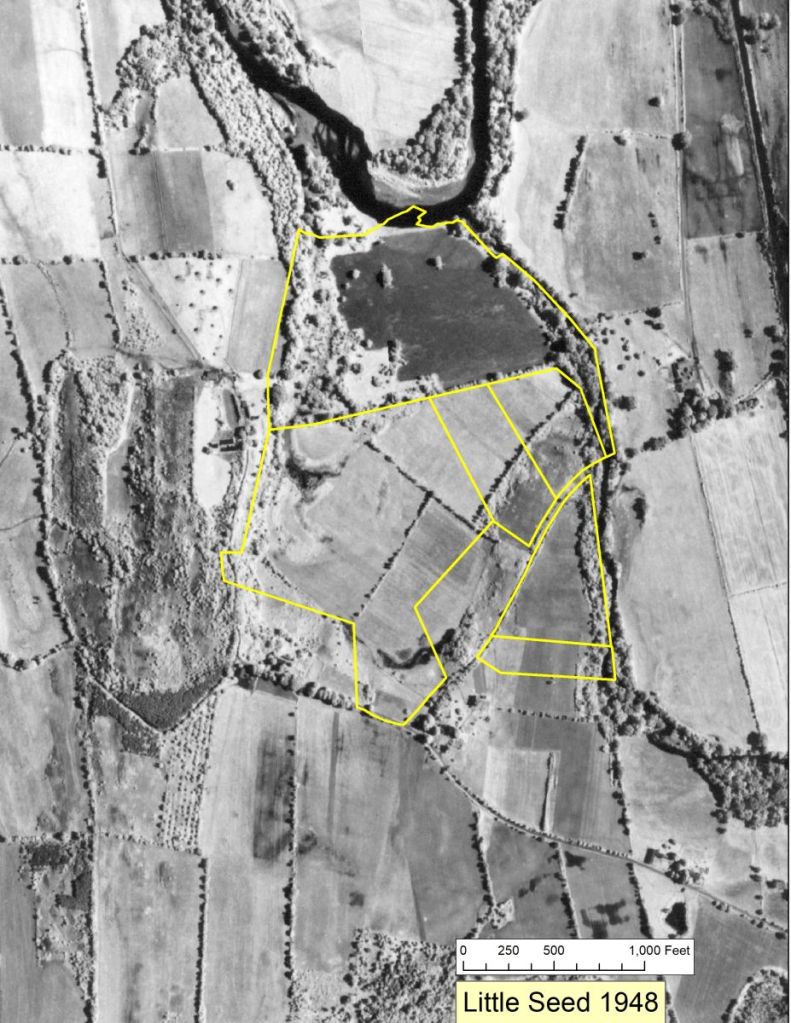

In 1948, the area around Little Seed was somewhat more open, but one of the main differences is the evident movement of the Kinderhook into the northern part of the farm since that year. Aside from that erosion, the northern pasture outline remains largely unchanged, but the smaller fields south of that have been united into a single large field (although, in practice, that is actually divided into a checkerboard of pasture and vegetable beds without large hedgerows).

As roughly indicated by the hot pink arrows, we visited the core of the farm, moving along its southeast edge until we reached the far, currently unoccupied pasture. We then headed northwest, passing by and around some veggie beds, nosing into pasture again before heading east along the hedgerow. We did visit the northern section and the banks of the Kinderhook, although by that time the rain clouds were rolling in.

Little Seed has plenty of loosely tended edges as shown by this photograph taken at point 1 looking southwest. In this picture, there is Common Milkweed, Fleabane and (in the background) Canada Thistle, all in flower.

As this photograph (looking southwest between points 1 and 2) shows, some of the same flowers come in around the veggie beds.

As this picture (taken at point 2 looking northeast), Fleabane is relatively common in the currently unused pasture.

This last landscape shot, taken looking west from around point 3, shows recently grazed pasture on the right and less recently grazed, fleabane-exuberant, pasture on the left.

Zooming in on some of the plants, we found Blue-eyed Grass (Sisyrinchium montanum) flowering in one of the pastures. This native plant (which is not a true grass!) can be found here and there in meadows, where its grass-like leaves blend in until its delightful flower announces its presence.

Another native plant, the Clammy Ground-cherry (Physalis heterophylla) was found in unmowed vegetation along an irrigation line. This is a wild relative of potatoes, tomatoes, eggplants, and peppers.

American Germander (Teucrium canadense) was found in several places along the deer fence surrounding the vegetable fields and also along the edge of the riparian forest of Stony Kill. This species is a native member of the mint family.

The native vine Moonseed (Menispermum canadense) can easily be recognized by its uniquely-shaped leaves with their stalks attached slightly underneath the leaf blade. Here it mingles with the invasive Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) on the edge of the riparian forest along Stony Kill.

The native Thin-leaved Sunflower (Helianthus decapetalus) is quite common along the forest edges. It will produce small yellow flower heads later in the summer.

Toringo Crab Apple (Malus sieboldii) is a rapidly-spreading small tree in the north-western part of Columbia County and has been classified as an invasive plant in our region. At Little Seed Gardens, it is the most common woody plant along fence lines. Unfortunately, it still is planted as an ornamental in gardens because of its beautiful white spring bloom. Birds love its small fruit (which turn orange when ripe) and disperse its seeds all over…

Toringo Crab Apple has variably-shaped leaves. These lobed leaves are from a young plant. Branches that flower and bear fruit usually have more simple, unlobed leaves.

Butterflies were not particularly active, perhaps in part due to the overcast conditions. Nonetheless, we saw about one dozen species. I only saw one Monarch. It would not be surprising if they laid eggs on the ample Common Milkweed on the farm.

We have two common species of Sulphurs here – the Clouded and the Orange. The Orange Sulphur often, but not always, flashes egg-yolk orange in flight, both species regularly have white females. This individual? Yes, it’s either a Clouded or an Orange… I’m not placing a bet. The Orange has become notably more common after its caterpillars discovered alfalfa as a food plant.

And one Red Admiral (sorry for the bad photo). Both Monarch and Red Admiral probably do not overwinter in the region, meaning that each year they must recolonize from the south. Both do breed here, but those following generations must head south if they are to survive. Red Admiral caterpillars feed on nettles, which probably occur in the wetlands or stream sides around the farm.

A few Great Spangled Fritillaries flew through during the surveys. We have two or three large fritillary species in the region, but only the Great Spangled as so complete a broad tan band between the silver spots of the hind wing. Their caterpillars are violet feeders.

The little Eastern Tailed-blue is common in our fields. The males are markedly blue on the top, but the females, like this one, are sooty.

Another little butterfly of fields is the American Copper. Ironically, given the name, some now suspect that, at least here in the East, this species was imported early in the period of European colonization.

Claudia spotted this little beauty while doing plant surveys along the edge of the southwest pasture. The Grey Hairstreak is one of our most common hairstreaks (which isn’t saying much given their general rarity as a group). This relative abundance shouldn’t be surprising because, as one guide book noted, their caterpillars “will reportedly eat almost anything”.

Pearl Crescents are relatively small butterflies, marked with orange and black. This pair was inspecting the mud around a former livestock watering spot. It’s thought that they are probably seeking salts deposited in cattle urine.

Another somewhat blurry photo, but good enough for an ID. This is a Black Swallowtail, of which we saw three individuals. These butterflies are occasionally considered pests because their caterpillars feed on members of the carrot family. The local species most likely to be confused with this butterfly is the Spicebush Swallowtail. The Eastern Tiger Swallowtail also has a dark female form, but it is most common to the south.

Skippers are fast-flying, moth-like (because of their big bodies relative to their wings) butterflies. This is our largest skipper, the Silver-spotted Skipper. Its caterpillars feed on a variety of legumes and it can be relatively common in farm fields, although I have not heard of it referred to as a pest on any leguminous crop.

The Northern Broken Dash can be recognized by the ‘3’ outlined in white spots on its hind wing. (OK, so it does take a bit of imagination to see it.) This is one of three small, relatively drab, brownish skippers flying at this time of year. To honor the difficulty of distinguishing them, butterfly folks refer to those species as the “Three Witches”. Just saw a few of these Broken Dashes today.

Here’s the same species starting to open up its wings. Unlike most butterflies, skippers tend to open their wings into a ‘jet fighter’ formation with the hindwing flat, but the forewing at an angle.

Distinctly different, right? Admittedly, skipper ID is something of an art. This is probably a second species of “witch,” the Dun Skipper – the drabbest of the lot, although it often has a vaguely greenish/gold hue to its head. The Dun Skipper caterpillars feed on sedges, while those of the Northern Broken Dash are grass feeders. The third “witch” is another grass feeder, the Little Glasswing. We didn’t see it today, although we did see it earlier in the week at a farm farther south.

The last butterfly for today is this one, caught mid-flight. This is the so-called Question Mark, named for the white dot and arc seen on the underside of its hindwing (and visible here). I only saw this species along the wooded edges. A Least Skipper and probable Cabbage White were also logged but not photographed.

Dragonflies seemed more common, but less diverse than butterflies. Indeed, I noted about 70 of them during the roughly 2 hour survey, but only roughly half that number of butterflies. However, I only ID’d four species of dragonflies vs. roughly a dozen species of butterflies. These are two Widow Skimmers, the most common species I saw during my wanders.

The second most common dragonfly were the Eastern Amberwings (aka ‘Snitches’). These are our smallest butterflies and the golden wings of this individual mark it as a male.

This mottle-winged individual doing a headstand is a female Eastern Amberwing. Males and females often differ markedly in coloration.

Some dragonflies seem to outshine butterflies in terms of color. This is the aptly named Halloween Pennant. Another relatively common dragonfly of grassy fields.

The young of all our dragonflies are aquatic, so these species are probably just visiting the fields for feeding. All of our dragonflies are predators and feed on other insects. These three species (and a fourth, the Blue Dasher) raise their young primarily in still or slow waters, and are probably coming from adjacent ponds or wetlands. The rarest dragonflies on the farm might be found along the Kinderhook, but our time was running out by the time we made it to the Creek. Creek dragonflies seem less likely to spread into adjacent fields.

Fifteen to twenty years ago we also did butterfly surveys at Little Seed. Many of the same ‘suspects’ appeared, but also present were several wetland butterflies – Bronze Copper, Mulberry Wing, and even a Dion Skipper (see shot from Little Seed in July 2010 above, one of only two records we have from Columbia County). Across those surveys, we averaged about 1 butterfly spotted per minute; during yesterday’s surveys, we averaged about half that, largely because we saw much fewer Cabbage Whites.

There are various, non-exclusive explanations for these differences. Foremost, no single day of surveys should be taken as representative. The weather was cloudy and hot yesterday; butterfly activity may have been reduced. Further, butterfly populations can fluctuate markedly across years, because of certain climatic conditions or other factors that boost or bust a given species’ natural history. Generally, this does not seem to have been a good Cabbage White year. Additionally, as a pest species, efforts may have been made on the farm to control this species in particular, although we have not yet talked to Willy and Claudia about that. The relative absence of wetland species might again be chance – each species of butterfly has its own flight calendar and we may have just not hit it right this year (although we know some of those wetlands species are currently flying elsewhere). Alternatively, perhaps some of those wetlands have dried or otherwise been altered – a clue to explore.

Insects rarely provide explicit answers about habitat change but they provide hints and, heck, they can be pretty! (For more on regional butterflies and our recommendations for good field guides, see here.)