This a longish blog, so here are some anchors you can use to jump to a section of particular interest:

Introduction (a virtual farm tour)

Plants of Harrier Fields Farm (by Claudia)

Insects of Harrier Fields Farm (by Conrad)

Birds of Harrier Fields Farm (by Will)

Introduction

We made two July trips to Harrier Fields, the farm of Mike Scannell and Joan Harris. The first, on 14 July, only involved Conrad snooping for bugs, but on 30 July, we returned with a ‘full crew’ also including Will Yandik on birds and Claudia on plants.

Harrier Fields Farm owns or leases about 80 acres of pasture and 100 to 150 acres of hay land. The Farm’s focus is on the breeding and organic production of Red Devons – hearty, beef animals who prosper on grass.

Most of the home farm is in pasture, including an old orchard, which provides shaded grazing in the hottest weather. The farm is bordered by conventional farmland on three sides.

During the mid-July visit, many of the pastures were tinted the light blue of flowering Chicory, and Common Milkweed flowers dotted the fields. While Chicory is a European plant, it nonetheless can provide important mid-Summer nectar resources.

Some Plants of Harrier Fields Farm (by Claudia)

(or return to Table of Contents)

Almost the entire area of the farm is managed as permanent pastures, which are occasionally mowed for hay. There are few trees, other than some shade trees around the buildings, the widely-spaced full-size apple trees (mixed with an occasional pear, Wild Black Cherry, and—what we believe to be—Swamp White Oaks) in the “orchard pasture,” and the occasional tree in hedgerows delineating most of the perimeter of the farm. The surrounding land is mostly farmland, with a small area of upland shrubland just to the east and a patch of young hardwood forest to the north.

During a morning’s worth of botanical inventories, we found a total of 65 different plants growing in the pastures, 22 of which were native species. However, most of the native species occurred in the pastures in low densities. The hedgerows harbor a higher percentage of native plants, even though they are mixed with a handful of enthusiastic non-native species (some of them classified as “invasive”). The most common non-native hedgerow species, like on many other farms, were Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora), Eurasian Shrub Honeysuckle (Lonicera morrowii/bella), and Oriental Bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus). Compared to other farms, there was a notable scarcity of Toringo Crab Apple (Malus sieboldii), Tree-of-Heaven (Ailanthus altissima), and Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris), all of which are classified as “invasive”.

The following set of pictures shows some of the native (and potentially native) shrubs and vines found in the hedgerows.

Some Insects of Harrier Fields Farm (by Conrad)

(or return to Table of Contents)

As Claudia has described, aside from a wettish patch behind one of the equipment sheds and some longer vegetation around various edges, Harrier Fields is a relatively uniform collection of upland pastures (sometimes under apple trees) usually in various stages of post-grazing. Because most upland pasture plants are European or, at least, relatively common, we did not expect a large variety of butterflies nor any particularly unusual species. Nonetheless, we had a few surprises:

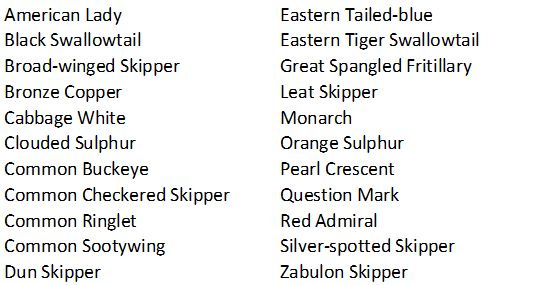

- An ample butterfly species list with more than 20 species. Before reading the list below, see if you can guess five of the species on it.

- A relative abundance of Monarchs. Harrier Field was one of the most ‘Monarchy’ farms we visited this year. Of course, part of that may have been because we just so happened to hit a day with a wave of migrants or hatchings. But it was not difficult to understand why we might be seeing so many Monarchs – Common Milkweed abounded and, given the rotational grazing, was likely available in various ages. One Monarch management tip is making sure that one not only has milkweed on a site, but also that one has various ages of milkweed – it seems that egg-laying females prefer milkweed that is young and tender, not old and leathery. Given that Monarchs engage in egg-laying throughout the Summer, ensuring that there are young patches of milkweed throughout the season can be important.

- An abundance of Least Skippers. Least Skippers are not particularly rare. Indeed, they are probably one our most consistently observable skipper species. So what was surprising was not that we were seeing them, but rather where we were seeing them. This species is generally associated with relatively low moist ground, such as the edges of ponds or wetlands, or moist drainage ditches. It’s thought this association is at least partially due to its caterpillar’s use of moist-soil grasses , such as Rice Cut Grass. However, according to the Connecticut Butterfly Atlas, captive females have laid eggs on Little Bluestem (hardly a wetland grass!), and the caterpillar’s diet is thought to be broad. So perhaps it should be no surprise that we found this dainty little butterfly weaving its low way through the high and dry pastures.

- The presence of Broadwing Skipper. This species of large skipper shares some of the moist habitat preferences of Least Skipper, so it was not surprising to see the two species together. But, as with the Least Skipper, it was surprising to find them in the middle of an upland field. We have most regularly seen them along the Hudson River, in places where one of their most common food plants, Common Reed, is present.

- The presence of Bronze Copper, a third wet-area butterfly. The snappy Bronze Copper is one of those butterflies who seem to be reasonably wide-spread but rarely common in any one spot. Its status is somewhat unclear, being considered ‘Vulnerable’ in PA, ‘Imperiled’ in MA and CT, and ‘Critically Imperiled’ in NJ. It is currently ranked as ‘Apparently Secure’ in NY. Its caterpillars feed on docks, and Claudia reported the presence of both Curly and Broad-leaved Docks in the pastures. It’s possible that this butterfly is more numerous along the banks of the Muitzes Kill tributary, about a quarter of a mile to the east.

- Common Buckeye, Common Checkered Skipper, and Common Sootywing were all present. Despite their “common” names, these three species aren’t particularly common in our region. All are abundant species farther south, but they sometimes push north during Summer. None are thought to be able to overwinter at our latitude. Their presence at Harrier Fields this year was only mildly surprising, because it was a banner year for southern butterflies. Aside from these three species, elsewhere we or colleagues have noted Giant Swallowtail, Variegated Fritillary, Little Yellow, Fiery Skipper, and Cloudless Sulphur – all southern species. Whether this is an indication of things to come or more of a one-off, we don’t know yet. There are historical records of northwards ‘explosions’ of southern species, perhaps during years when conditions are particularly good for them further south, but climate change may also be paving a way for them.

Aside from these butterfly insights, we made a few odds ‘n ends insect observations that we include below.

Sometimes agricultural demands and/or the lay of the land mean that a given farm does not have a great diversity of habitats. Harrier Fields Farm illustrates that, given organic, land-conscious practices one can, nonetheless, host an array insects.

Some birds of Harrier Fields (by Will)

(or return to Table of Contents)

The structural diversity of plants found at Harrier Fields has allowed a wide variety of birds to feed, shelter, and nest here. When walking this farm, one gets the feel of an older model of land stewardship, one that places less emphasis on ‘tidy’ edges and pastures. Birds can be found nearly everywhere on this farm but two guilds of birds stood out — namely, those that nest and feed in lightly stocked pastures, and those that nest and feed in hedgerows.

Claudia includes in this post a beautiful series of photos of fruiting plant species of the hedgerows (high bush cranberry, arrow wood, elder, dogwood, and grape) and all of these plants provided ample food for birds. As we visited in late July, just as many of the region’s farm stands offered a wide variety of fruit for sale, the hedgerows here contained their own bounty and many juveniles, those awkward ‘teenaged’ birds no longer fed directly by their parents but not yet fully independent, could be found in flocks with adults feeding on this late summer fruit.

The juvenile Northern Mockingbirds continued to beg for food from their parents with a unique rasping call, but the adults were having none of that and left the young to forage for themselves. There is an active area of ornithological research investigating how some species of birds may teach their young about suitable food sources though direct example. It surprised me to see the mockingbird clan move on to feeding on sumac berries — usually a drier less nutritious fruit that most birds pass over until the dead of winter when there are few other options (Watch for birds like mockingbirds and Eastern Bluebirds feeding on sumac in December and January). I thought perhaps the birds might be feeding on insects on the sumac but in the field of view in my binoculars I could observe the mockingbird swallowing sumac fruits. Shrug. Maybe sometimes the bran muffin wins over the chocolate-chip cookie. Birds, like mammals, make complex food choices.

Baltimore Orioles, Blue Jays, House Finches, and Song Sparrows all joined the feast.

A pair of cedar waxwings alighted on the patch of jewelweed and loosetrife that Claudia describes above. They appear to be feeding on something on the loosetrife — could it be the Black -margined Purple Loosestrife Beetles (shown in Conrad’s earlier photo)?

Before binoculars became cheap and readily available, most ornithologists worked with shot guns, shooting birds first, then identifying the skins later. Thankfully, we have moved on from that practice but some of the names of birds are holdovers from the era of identifying birds with the feel of your hands. Waxwings indeed have a red waxy spot at the tip of their secondaries that can be very hard to see, but easy to feel in the hand. Sharp-shined hawks, a local bird-hunting raptor, are also best understood when you trace your fingers over their forelegs. You’d have to squint to see the red belly of our common Red-Bellied Woodpecker at your backyard suet feeder. Not so if you held it belly up in your hand.

The hedgerows at Harrier Fields are wonderful examples of habitats used by birds at the edges and margins of our economic use of the land. Outside the reach of a grazing Red Devon, or turn of the mower, these spaces provide room for wildlife and if we train our eye to see the life they contain we will no longer see them as ‘messy’ places in need of cleaning up, but rather enhancements to our farms.

Nearer to the economic purpose of Harrier Fields are the pastures and fields used by grazing cows, although these fields are also managed less intensively than the typical modern beef operation.

A fledgling Savannah Sparrow, a fairly young bird for this time of year, suggests that Savannah Sparrows successfully and recently bred in this orchard-grass dominated pasture. A group of 30 or so Bobolinks, another pasture specialist, flush from the grass and perch along the hedgerow. All of the male adults have shed their summer black, white, and yellow breeding plumage and molted into a straw-colored brown as they prepare to make one of the most stunning long-distance migratory journeys of our local breeding birds. Noah Perlut, a colleague of ours at the Applied Farmscape Ecology Research Collaborative, tags Bobolinks in Vermont and New York with transmitters that allows him to see their movements with tremendous detail. Noah has found that Bobolinks from our area launch themselves from the mid-Atlantic states in late summer on multi-day non-stop flights to Cuba and Venezuela. The athletic abilities of such small birds are among the wonders of nature.

.

My family has cultivated fruit trees in southern Columbia County for five generations, so the old orchard at Harrier Fields was a special treat to see. Apples were grown in the American colonies since the 1630s and were a staple on most northeastern farmsteads until the middle of the 20th Century. Most apples were used for making hard cider, although the Hudson Valley has a long tradition of drying apples for shipping and for fresh market use. The apple trees at Harrier Fields are very old examples, but they are more than a nostalgic pleasure.

The gift of visiting a new farm is the manner in which it makes me see my own farm with fresher eyes. I wonder if there is some corner of my home farm that could weather a longer fallow rotation, or a lane that could skip a mowing or two, or a less productive field that could be left to willful neglect. Can we make a living off of our own lands and leave something extra for wildlife? Where are the ecological hotspots on your own farm or property?