Transgenerational Farm is a very small market garden on approximately three leased acres adjacent to the hop yard of Arrowwood Farm. It is surrounded on three sides by forest. We were able to only visit briefly (2 hours) on 30 August 2024, and it was an overcast morning—hardly the ideal conditions to see many insects.

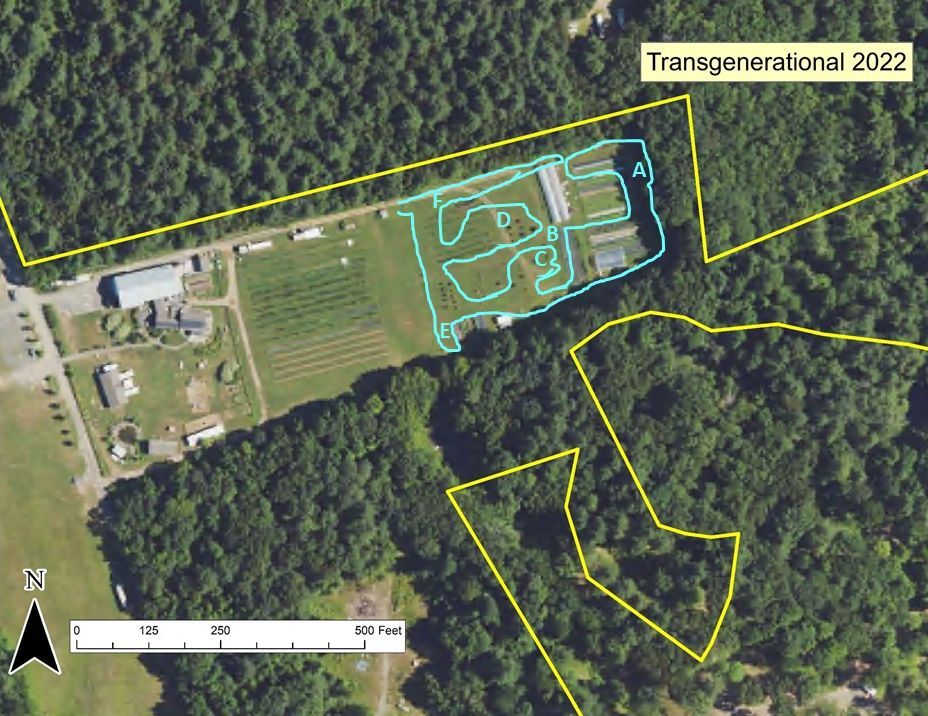

The following aerial photo traces the approximate route taken for the plant surveys and letters indicate locations of the habitat photos we share below.

Botany

(or skip to Insects)

by Claudia

The closely-mowed lawn had its share of typical European lawn weeds, such as the two species of plantains, Red and White Clover, Dandelion, two species of crabgrass, and the usual set of European cold season grasses (Timothy, Tall Fescue, Kenntucky Bluegrass, and Smooth Brome Grass). However, it also had the native Common Blue Violet and Indian-tobacco, in addition to many of the native and non-native weeds also found in the tilled beds. I was surprised that in some areas, the most abundant grass (at least late in the summer) seemed to be the native Nimblewill Muhly (Muhlenbergia schreberi).

The weeds in the tilled beds were the usual cohort of familiar annual warm-season weeds (Common Ragweed, Horseweed, Lamb’s-quarters, pigweeds, crabgrasses, foxtails, etc.), at least 25 different species in total.

I did meet one new weed, which I had not seen on any other farm before: Clammy Glandular-goosefoot (Dysphania pumilio; since then also seen at the Hudson Valley Seed Company). Originally from Australia, it is suspected to have been introduced to North America as a contaminant in sheep’s wool and seems to have spread throughout southern New England and obviously into the southern Hudson Valley. It is also documented from a few isolated counties in other parts of New York.

Near one of the sheds, I spotted another (to me) unfamiliar weed, which I was able to key out as Urban Goosefoot (Chenopodium urbicum). Originally from Europe, it reportedly has established itself in scattered locations throughout Eastern North America and the Midwest. However, I have never noticed it in the Hudson Valley before.

Finally, the third new weed was Indian Strawberry (Potentilla indica). It grew under the blueberry bushes and its watery berry tasted of absolutely nothing! This species, which was introduced from India, still seems to be quite rare in our region, but is a common weed further south.

Two nightshades were growing as weeds near the compost pile, probably both wild-growing plants of cultivars. I suspect the one on the left with the larger flowers and rather smooth leaves to be a variety of tomatillo (possibly Physalis philadelphicus or P. ixocarpa). The one on the right, with the smaller flowers and hairy leaves is probably a variety of ground cherry (possibly Physalis peruviana). I don’t usually see these species growing in the wild, so don’t feel completely confident with their identification. If anybody has any alternative suggestions, I’d be happy to hear them!

Finally, let’s have a closer look at the unmowed herbaceous vegetation along the deer fences and the adjacent band of shrubs at the edge of the forest (this image shows the southeast corner of the deer fence). Along the fences, we have some of the usual edge suspects, such as the invasive Tree-of-Heaven, Multiflora Rose, and Oriental Bittersweet.

However, along the south fence, we also spotted a small group of the native Early Goldenrod (Solidago juncea) growing out of some pallets. While not exactly a rare species, this goldenrod is not common, either. It does not compete well with the four rhizome-forming old field goldenrods that are generally very common in our landscape (though not at Transgenerational Farm). Note how the Early Goldenrod in the image is surrounded by the invasive Japanese Stiltgrass and adjacent to a patch of the almost ubiquitous invasive Mugwort.

Possibly the most common native wildflower along the south fence was the light-blue flowering Heart-leaved Aster (Symphyotrichum cordifolium). It can be recognized by its large, heart-shaped stem leaves with sharply serrated margins. However, note the tiny leaves on the flowering branches!

There were also a few plant of the native white-flowering Lance-leaved Aster (Symphyotrichum lanceolatum).

The shrub layer along the forest edge certainly had its share of invasive species. Pictured here from left to right are Autumn Olive, Privet, and Multiflora Rose, but we also observed quite a few Japanese Barberry and Eurasian shrub honeysuckle (Lonicera morrowii or L. bella).

However, native shrubs and young trees from native species in the adjacent forest were also common along the edge, and we observed Staghorn Sumac, Sassafras, Black Walnut, American Elm, Sugar Maple, Red and Black Oak, Black Cherry, Hackberry, Red Cedar, White Pine, and even Hemlock. In fact, this was the only one of the nine farms visited this season, where we observed Hemlock.

Not surprising, given the very small size of Transgenerational Farm, we observed the least overall number of plant species here compared to the other eight farms we visited this season. Much of the native plant diversity we did observe occurred in the narrow, unmowed herbaceous and shrubby vegetation along the deer fence and in the adjacent forest.

Some Insect Notes.

by Conrad.

It was spitting rain on the 30th of August when we visited Transgenerational Farm. Neither the lateness of our visit nor the weather were propitious for seeing abundant butterfly life and, in fact, we only noted a quartet of butterflies – Pearl Crescent, Eastern Tailed-blue, Least Skipper, and Monarch. Nonetheless, the abundant ‘edge habitat’ that Claudia noted early makes me think that a sunny July visit would have resulted in substantially more sightings. And, besides, butterflies aren’t the only game in town…

In our own regional surveys, we have records from 21 April to 7 October (and they probably fly earlier and later, but we’re just not out surveying butterflies!). That doesn’t mean that there’s a constant Pearl Crescent spigot, instead there appear to be multiple broods, i.e., distinct batches who appear across the season. As I alluded to in an earlier post, Crescent taxonomy seems to be something of a mess, and multiple, sometimes overlapping, generations raise the possibility of ‘cryptic species’ – previously undetected species who, because of high similarity (at least in our eyes) to named species, go unnoticed. The Northern Crescent, a very similar looking butterfly, also seems to occur regionally. We also used to have a third species of Crescent – the Tawny Crescent, but that species has apparently nearly disappeared from the Northeast. Mind you, post a Crecent photo on iNaturalist, and few people are willing to go out on a limb and provide a species ID, plus genetics papers have detected some evidence of interbreeding, so who know what’s happening! (A paper published just this year, does suggest that these three species are more or less distinct, at least in the West.) Who thought such a ‘simple’, common butterfly could be so confusing?

The Eastern Tailed-blue is another common butterfly, but why the tail? That little wisp looks like something of an afterthought and it’s hard to imagine its potential function, at least from this angle. But think of what it looks like with the wings closed…

If you were a bird dashing by in search of meal, mightn’t you sometimes mistake that tail and associated wing dots for eyes and antennae? Maybe you only make that mistake once in four times, but, from the perspective of the species, that’s a huge plus and pretty strong evolutionary selection. Indeed, not infrequently we see tailed butterflies whose tails have been replaced by beak-shaped gaps.

Honey Bees are not native, they were brought from Eastern/Southern Europe by early European settlers because of their honey-making talents. (I do wonder how many sea-sick colonies survived the trans-Atlantic voyage; presumably the voyage would be made during Winter, using a hive stocked with Honey.) However, aside from honey, Honey Bees have another advantage – at least in part because of their honey-making and social skills, they can ‘get up early’ in the Spring and start pollinating while conditions are still relatively cold. Some native bees, such as bumble bees, mining bees, and mason bees, also get going early, and, in healthy ecosystems, they can usually handle the pollination demands of early fruit flowers, but Honey Bees are sometimes considered a safety net for Spring pollination. Aside from Spring, Honey Bees are usually pretty dogged in foraging during cool and rainy weather, as these images suggest. Unfortunately for the native bees, there’s some evidence that high Honey Bee populations can hamper native bee foraging.

While adult Four-toothed Mason Wasps primarily feed on nectar and, perhaps, pollen, they prepare their young for the World by supplying the burrow-nursery of each cossetted egg with a live, but paralyzed caterpillar. When the egg hatches, the larva devours the caterpillar. Given that those caterpillars can sometimes be agricultural pests, such wasps have generally been classed as beneficials. Clearly, agronomists, not moths, are making that call.

Blue-winged Scoliid Wasps follow a slightly modified version of the Four-toothed Mason Wasp’s game plan. Like the previous wasp, the adults feed on nectar and pollen, hence the first image of them on flowers. But their time on the ground, as in the above photo, is spent looking for beetle grubs, specifically those of Japanese Rose Beetle and the Green June Bug. Once found, the grub is again paralyzed and an egg is laid upon it. On hatching the wasp larvae feeds on the adjacent grub. Again, since white grubs and Rose Beetles in particular are often considered pests, seeing a bunch of these likewise mild-mannered solitary wasps is an indication that biocontrol is in action.

Many of our so-called “beneficials” are generalists. Spiders, for example, will seemingly eat a bee or prey mantis (both considered “beneficials” in their own right) with as much gusto as they will consume some hapless, pestiferous herbivore. Likewise, many of our ground beetles will happily eat seeds and/or pollen of an array of plants, whether those happen to be your crops or your weeds. Life is complicated and the net effects of these creatures on production will depend on your particular agroecosystem. Certainly, some generalization are possible, but nothing can completely substitute for keeping an eye out for the creatures you see in action in your own fields.

P.S.: That mystery butterfly was a Least Skipper.