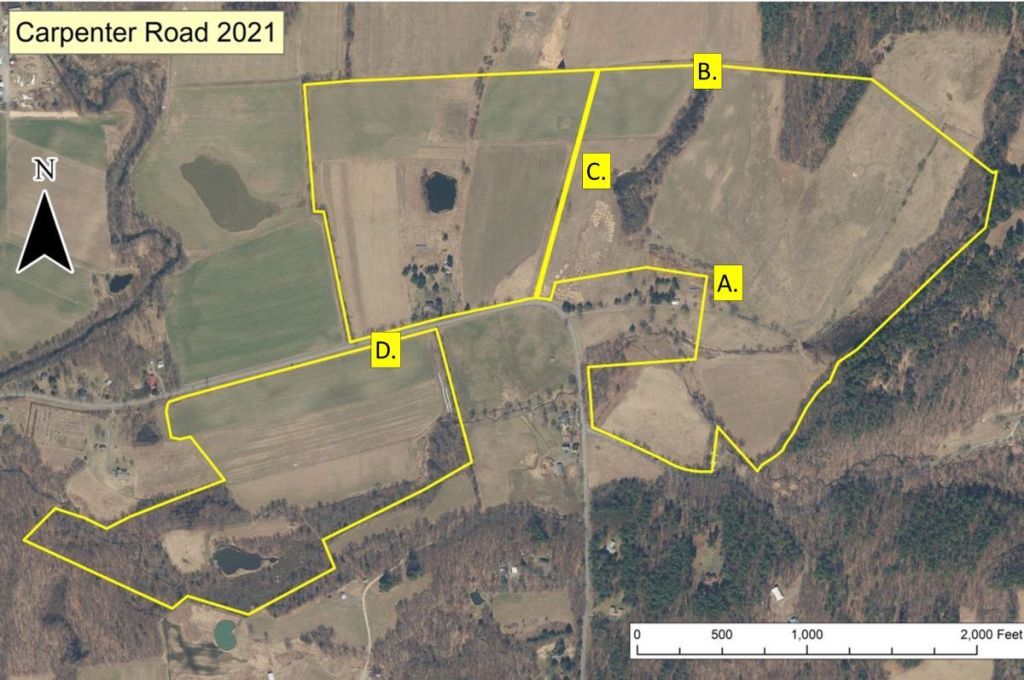

These Hawthorne Valley Farm-managed fields are comprised of hay field, pasture and ploughed ground and are leased from three nonfarmer land owners. They are interspersed with a few hedgerows and wood patches. The parcels are located along Carpenter Road, just north of Philmont, Columbia County. The eastern property belongs to Arthur’s Point Farm, a native plant nursery with ongoing reforestation/orchard establishment on some of its fields. The western property has a small apple orchard managed by the owner, but that was outside of our survey area.

As we did in our Harrier Fields post, this one is a multi-organismal extravaganza, what follows is Claudia describing plants, Conrad describing mainly butterflies, and Will describing birds. You can use the below anchor points to navigate to your favorite section:

Botanical Observations

by Claudia.

(29 August 2024, 6 hours)

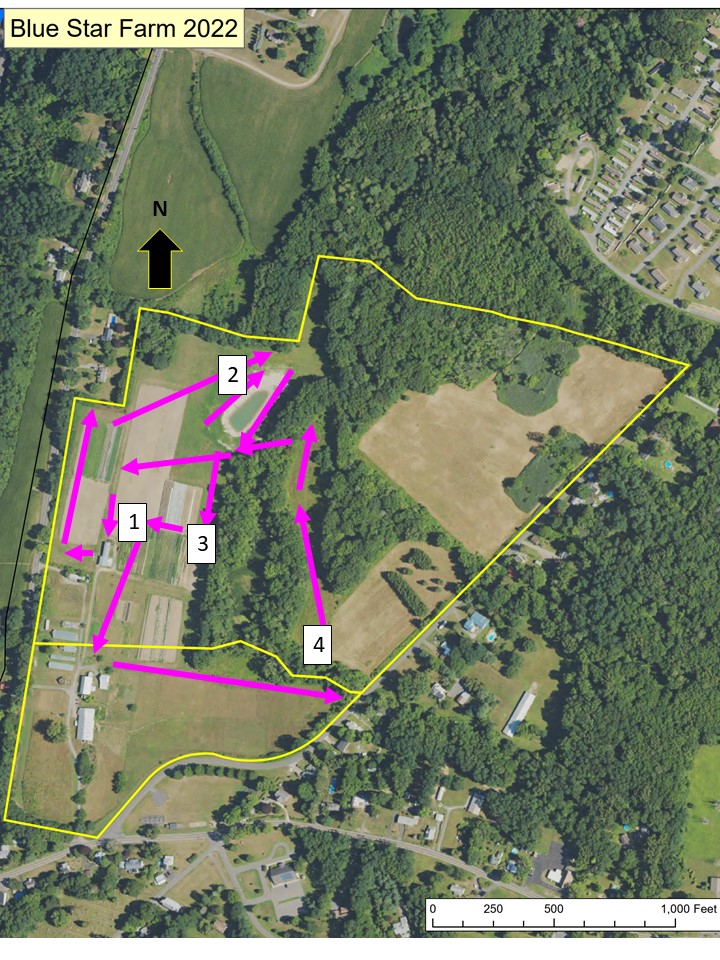

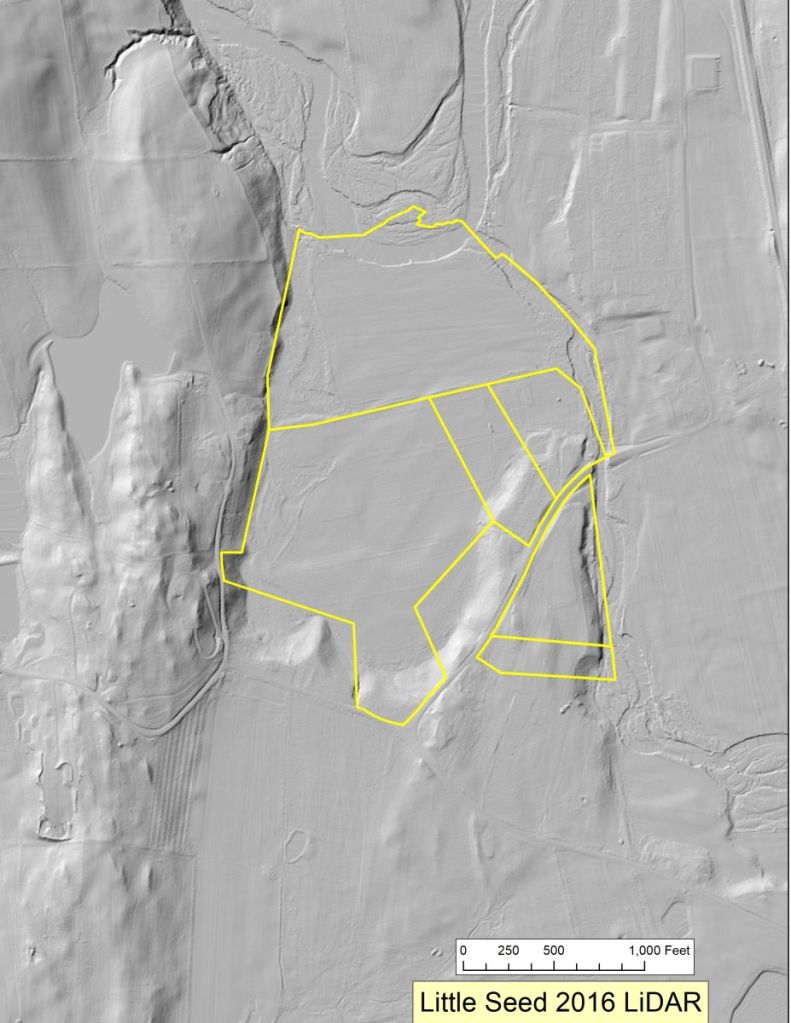

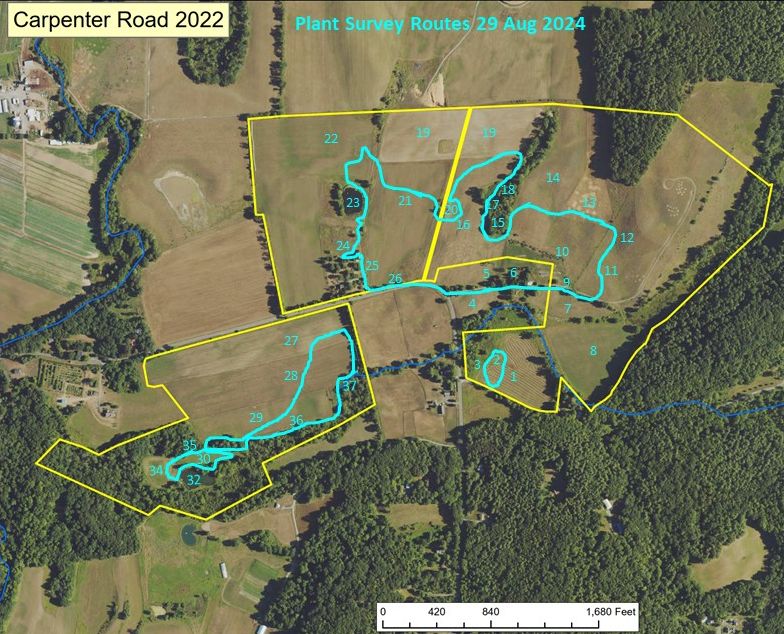

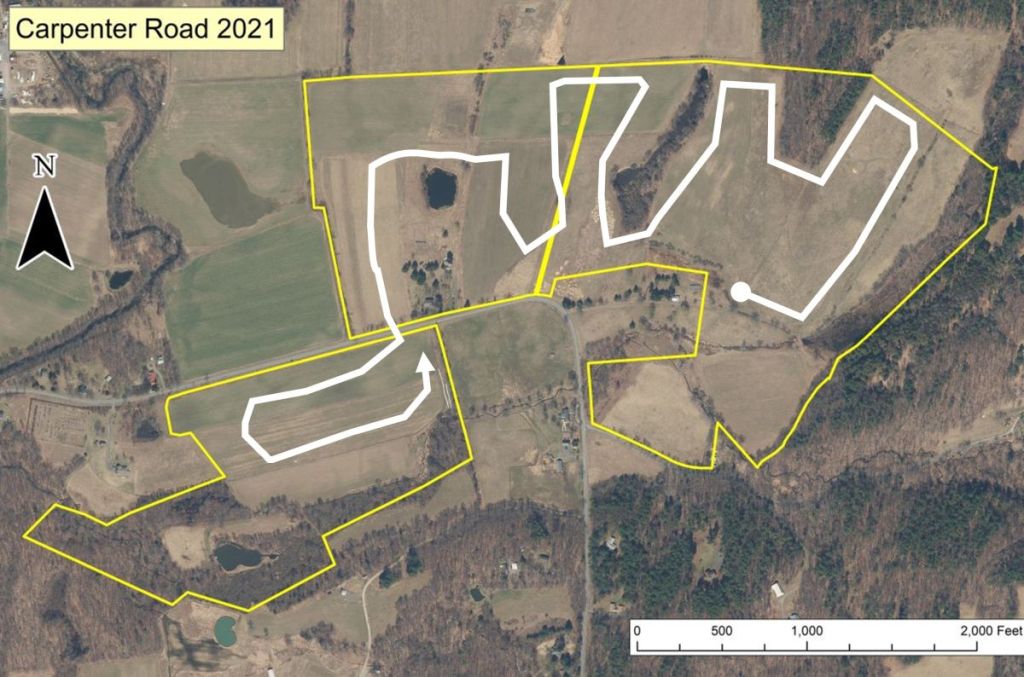

The botanical survey only included agricultural areas managed by Hawthorne Valley Farm and some adjacent non-agricultural habitats. The following map shows the approximate routes walked during the survey. Numbers indicate points/areas where botanical observations were made. I will refer to them throughout this blog.

Most of the field north of the entrance of Eagle Rock Road (#1 on the map) was dominated by Yellow Foxtail, an annual, warm-season grass originally from Europe, which seemed to be doing particularly well on tilled ground on several farms we visited this year. The area of greener, lower vegetation visible here is a wet spot in the field (#2), which supports sedges and Sensitive Fern. The yellow strip of vegetation along the edge of the field (#3) is a wet meadow that is fenced off and does not get tilled.

These delightful flowers of an unusual color belong to an uncommon European annual with a fun name: Scarlet Pimpernel (Anagallis arvensis), which is also referred to as “Poor-man’s Weatherglass,” because it supposedly closes its flowers when the sky becomes cloudy, “Red Chickweed,” for obvious reasons, or “Poison Chickweed,” because it contains toxins. We find this small plant occasionally along roadsides and in tilled fields (#1), but in our region, it never seems to become common enough to consider it a serious agricultural weed.

Another uncommon European weed spotted in the same field (#1) is Flower-of-an-hour (Hibiscus trionum), which has a flower of typical Hibiscus-shape, but unusual color combination.

The unmowed wet meadow at the field edge (#3) was composed of mostly native wildflowers, including four kinds of goldenrods, Blue Vervain (Verbena hastata), Pilewort (Erechtites hieraciifolius), Spotted Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis), Spotted Joe-Pye-weed (Eutrochium maculatum). It also harbored some invasive species, such as Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) and Canada Thistle (Cirsium arvense), which is a European species that might better be referred to as “Creeping Thistle,” to avoid the common misconception that this species is native to this continent.

The pastures and hayfields (#11) appeared mostly green from a distance.

Looking closer, they were composed of quite a variety of plant species: European cold-season grasses mixed with European clovers: White Clover (Trifolium repens), Red Clover (Trifolium pratense), and Bird’s-foot Trefoil (Lotus corniculatus). One can also see the European Common Bedstraw or “Wild Madder” (Galium mollugo) and Wild Carrot (Daucus carota), as well as the ubiquitous Yellow Foxtail (Setaria pumila).

Two native species that were quite common in these perennial pastures/hayfields, were Horse-nettle (Solanum carolinense) and Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca).

This shrub swamp (#18) is part of a small wetland complex that also includes an ancient swamp forest (#15), which seems to have never been completely cleared for agriculture. The center of the shrub swamp is dominated by the native Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis), which tolerates year-round “wet feet.” Some of the edges of the shrub swamp are dominated by the invasive Reed Canary Grass (Phalaris arundinacea; seen in the foreground).

A closer look at the Buttonbush reveals its tell-tale spherical seed heads. In mid summer, each of these spheres was covered with small, white, tubular flowers that are very attractive to a variety of pollinators.

This curious-looking vine is Burr-cucumber (Sicyos angulatus), a native member of the cucurbit family.

It was enthusiastically growing on Eurasian honeysuckle shrubs (Lonicera morrowii or. L. bella) around the edge of the Buttonbush swamp. This is one of the North American species considered invasive in parts of Europa and Asia.

There were several unmowed, herbaceous field edges (e.g., this east edge of #19), which support a vegetation composed of typical pasture/hayfield plants and native species, such as asters and goldenrods, which don’t tolerate mowing/grazing very well. These margins serve as sanctuaries for insects, as pantry for seed-eating birds, and provide shelter for all sorts of wildlife.

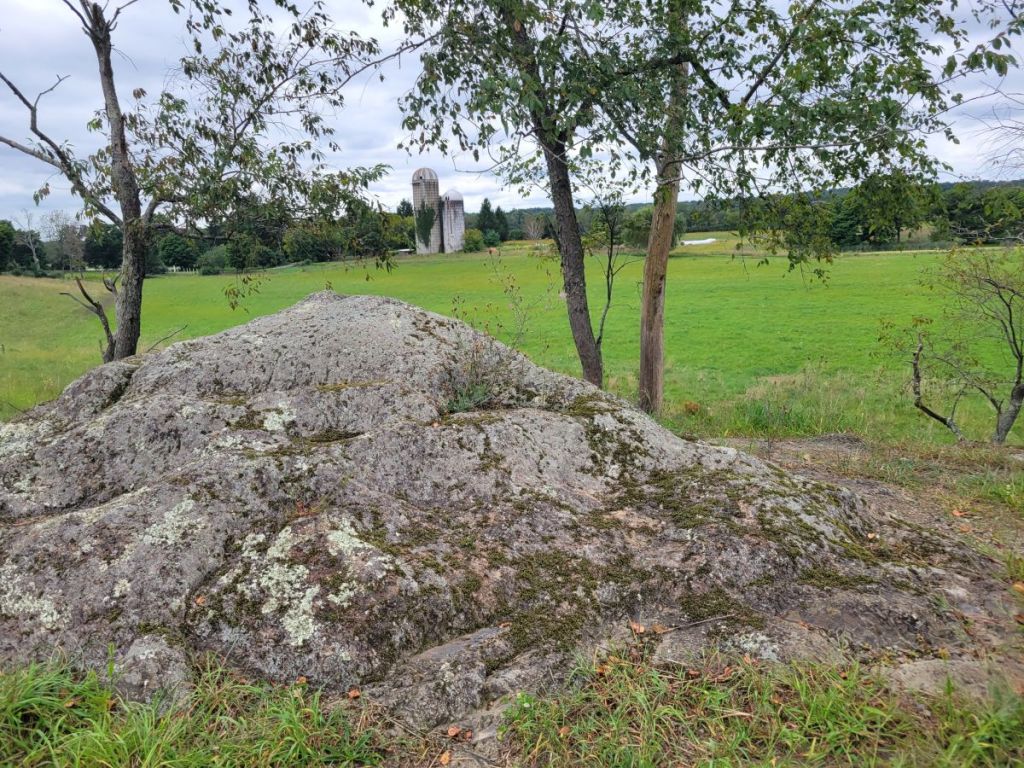

A small rocky knoll (#20) drew my attention because of its potential for unique plants.

On the rocks themselves I found a number of mosses and lichens not seen elsewhere on the Carpenter Road Farmland (but not uncommon in the larger region). There was also a small patch of Ebony Spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron) a native fern tolerant of dry conditions. The plants in the foreground are Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea jacea), a European meadow species with thistle-like flowers that often invades dry pastures in our area.

While an interesting scenic feature, the rock outcrop and surrounding dry pasture proved to be not as botanically-rich as hoped. One reason might be that this area has the only shade trees in this pasture, which might result in heavy use and associated trampling of the vegetation by grazing animals. (A snag on the knoll did seem to be a nesting site for American Kestrels.)

In contrast, the unmowed shore of this nearby pond was one of the few places on the land where native wetland plants abounded. These included two species of cat-tails (Typha latifolia and T. angustifolia), several species of sedges (Carex spp.) and bulrushes (Scirpus spp.), a nutsedge (Cyperus sp.) and a spikerush (Eleocharis cf. obtusa).

The tall vegetation next to the pond also supported the elaborate nets (with their characteristic zig-zag pattern) of several large Garden Spiders (Argiope aurantia).

The pond itself had some patches of floating duckweeds, which are often mistaken for algae. Instead, they are miniscule plants (which actually have microscopic flowers that grow directly on the floating leaves). This floating carpet seemed to be composed of at least three different species: the largest leaves belong to Common Duckmeal (Spirodela polyrhiza), the medium-sized ones to Common Duckweed (Lemna minor), and the really tiny ones to one or several species of watermeal (Wolffia spp.).

On an old compost pile near the silos south of the pond (#24), I discovered a big patch of the invasive Japanese Hops (Lupulus japonicas).

On the south side of Carpenter Road, there are three big fields (#27-29) with different plant compositions.

The unmowed, untilled field margin between #27 and #28 harbored a mix of native and non-native plants, including some tall thistles.

Closer inspection helped identify them as the native Field Thistle (Cirsium discolor), identifiable by their large flower heads and the characteristic white stripes on their spiny bracts (the otherwise green, little leaves that surround the flower head in a tile-like arrangement).

The tilled field (#28) had a cover crop of Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) and an abundance of annual agricultural weeds, including the native Common Yellow Nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus; in the foreground) and three species of introduced foxtails (Setaria spp.).

Three seed heads of foxtails growing side-by-side in the Buckwheat cover crop: Green, Giant, and Yellow Foxtail (Setaria viridis, S. faberi, and S. pumila; from bottom to top, respectively).

Another pond (#32) also supported a diverse wetland vegetation along its unmowed margins.

American Bur-reed (Sparganium americanum) was one of ten native species not noticed anywhere else during this inventory.

The herbaceous/shrubby field margin (south edge of #29) harbored a mix of invasive (note the ample Japanese Stiltgrass, Microstegium vimineum, in the bottom left corner of the image), native (Common Milkweed, Asclepias syriaca, and goldenrods, Solidago spp.), and European (Wild Carrot, Daucus carota) species. The structural diversity of such “soft edges” attracts certain songbirds and the diversity of plant species provides floral resources for pollinators.

Finally, a wet meadow (#37) along a small stream was exceptional in its density of native, late-summer flowers, including those of several species of goldenrods, Spotted Joe-Pye-weed (Eutrochium maculatum), Spotted Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis), and Purple-stemmed Aster (Symphyotrichum puniceum). The latter was not seen anywhere else during this survey.

Butterflies & Other Insects

or return to table of contents

by Conrad.

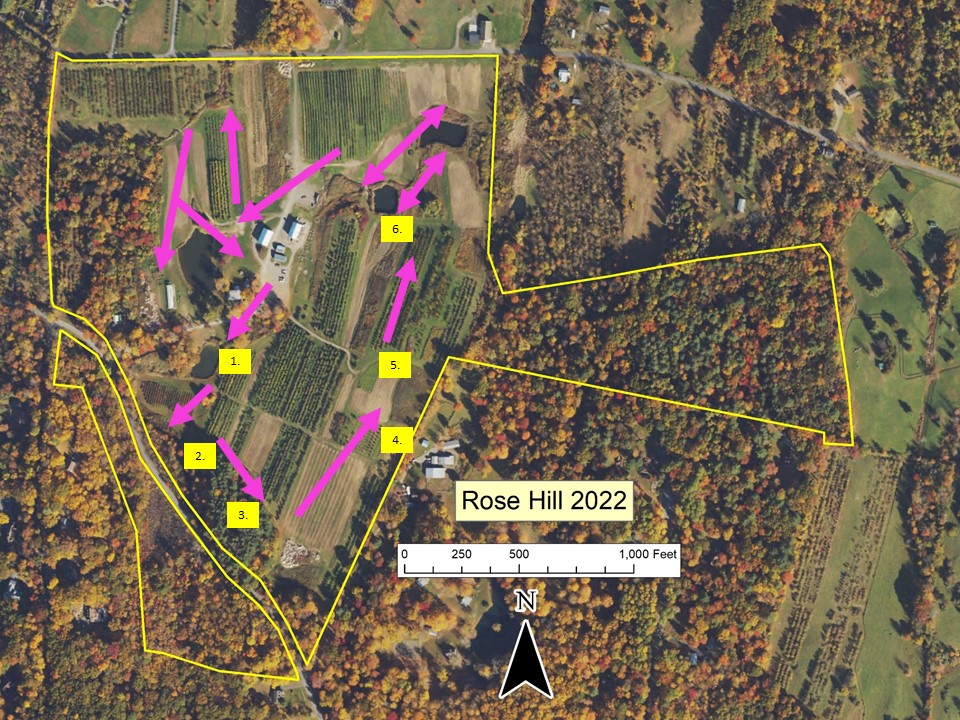

It was a generally warm and sunny 27th of August when I made my way around the Carpenter Road fields. I more or less followed the route shown below, winding through the open farm fields.

As I’ve tried to illustrate with this photograph, Black Swallowtails seem to be especially dedicated “hilltoppers”, often gathering atop hills. Perhaps this facilitates mating, a sort of innate “I’ll meet you at the top of the hill” social club.

Here’s another southerner who pushed north this year – the Common Checkered Skipper. Again, this is i-naturalist’s northernmost Hudson Valley sighting this year. There were apparently no New England records in 2024, however, it’s admittedly not as eye-catching as the Common Buckeye.

Clearly, ‘spider web on pumpkin’ camouflage.

And even more surprising, they were mating!

As we were preparing this, Will asked me why we observed so many southern butterflies this year. Aside from the species mentioned above, elsewhere in the region we or colleagues saw Giant Swallowtail, Cloudless Sulphur, Fiery Skipper, and Little Yellow – all of whom are also southern species. It’s hard to know for sure why this was the case. These are all southern species who have been recorded to occasionally make northern forays. For some of these species there are even 19th century records of such movements. One can imagine that such species are always probing the northern margins of their distribution, and when populations are particularly high farther south and/or conditions are particularly amenable farther north, they then appear in our area. Is their local appearance due to climate change? Could well be, but I don’t think we know enough about their ecologies to really pinpoint the cause of their appearances this past year. Time will tell whether this was a fluke year or, instead, the start of a trend. An interesting management question is, should we ‘plant ahead’? For example, should we seed more Partridge Pea or Prickly Ash (also southern species) so that the Cloudless Sulphur, Little Yellow and Giant Swallowtail find welcoming host plants for their caterpillars when they show up?

The Birds of Carpenter Road

or return to table of contents

by Will

The three Hawthorne-managed properties owned by three different households that we will simply refer to as “Carpenter Road” contains a broad range of habitats and with it, a broad diversity of birds to match. I visited these properties on June 24.

A common theme throughout my blog posts has been an investigation of unmanaged or lightly-managed edges, which can be productive foraging areas for birds seeking seeds and insects. These areas need not be designed and planted as wildlife strips, but rather through willful neglect can host a higher plant diversity than closely mowed lanes. That plant diversity often leads to structural diversity which provides cover for birds and insect diversity which provides food.

The Savannah Sparrow, a species of concern in NYS is quick to make use of unmowed edges around farm fields. Photo credit: Mike Birmingham

The diversity of native and naturalized vegetation provides many opportunities for a variety of bird to nest and feed

Barn Swallows and Red-winged Blackbirds foraged over the fields of grain on Carpenter Road and as one moved south of the road, a mature hedgerow of native trees and lightly managed meadow hosted an entirely different set of forest and shrub-loving species of birds.

American Robin, Carolina Wren, Downy Woodpecker, Field Sparrow, Gray Catbird, House Wren, Northern Cardinal, Northern Flicker, Orchard Oriole, and Yellow-throated Vireo could be found in the hedgerow. Another guild of water-loving species could be found near the small pond there including Common Grackle, Red-winged Blackbird, Warbling Vireo, and Yellow Warbler.

Because of the ephemeral nature of their preferred habitat, Chestnut-sided Warblers rarely stay in the same place for more than a decade or so. Photo: Mike Birmingham.

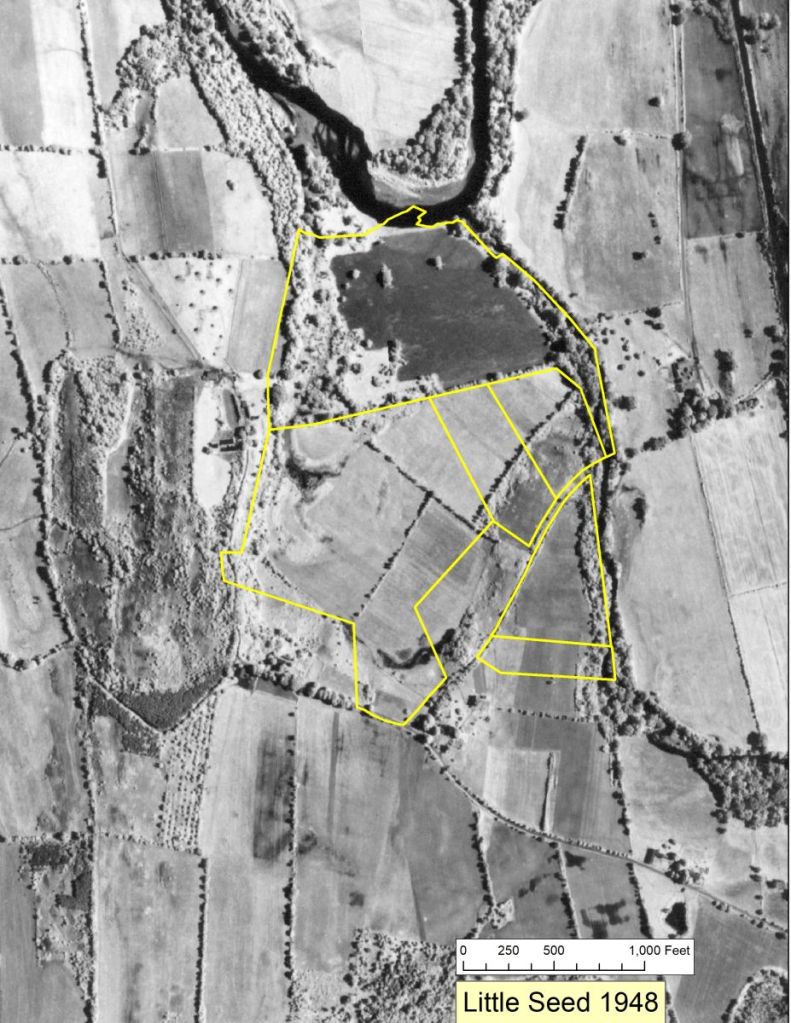

The song of the Chestnut-sided Warbler ‘Pleased Pleased Pleased to MEETcha!‘ rang from a group of young Red Maples. This bird can nest in a very small patch of suitable habitat, but they prefer young trees and thickets. Historically, this was a bird that followed natural disturbance or even logging, taking advantage of rapidly regrowing trees and shrubs. Once forests mature, this species moves on to other young patches. It’s likely that some part of the farm south of Carpenter Road was abandoned a few decades ago (see the 1940s aerial photo on Conrad’s post!) and the trees are in that habitat ‘sweet spot’ for this warbler.

We’ve lost about half the number of Chestnut-sided Warblers in North America since the 1960s as much of their suitable early successional forest has matured since the peak of agricultural abandonment a century ago. They likely colonized forests after fire and storm damage and in the wake of abandoned beaver meadows before European settlement. It’s possible that they were even rarer than today in the North America centuries ago of mature forest punctuated with Native American fields and encampments. This warbler has also suffered from severe habitat depletion on its wintering grounds in Central America as tropical foothills have been cleared to raise coffee. It is well documented that reputable “shade grown” coffee, from plantations that retain an intact canopy of native tropical tree species, greatly benefit this species. Something to ponder as we make our caffeine purchasing choices.

Chestnut-sided Warblers forage in leaves, searching for caterpillars, fly larvae, spiders, and leaf hoppers. They nest fairly close the the ground in shrubs, rarely more than six feet off the ground. They form monogamous pair bonds and actively defend their small nesting territories from neighboring species of warblers and other songbirds. It usually requires a good pair of binoculars to see them well, but once you track down this fast flitting species the spring males in particular can be a stunning reward of color.

To the north of Carpenter Road, Hawthorne Valley farmers have interplanted cereal grains in a matrix of clover and other cover crops.

A quick drive by and this field of wheat looks like any other…

A closer look shows that these cereal grains are not conventionally grown in a no-till regime with glyphosate herbicide because the edges and understory still host other photosynthesizing plants…

This understructure of clover and other forbs provides an essential understory for insects, the primary summer food for all North American songbirds

Conventionally grown row crops can be fairly unbirdy places since there is limited cover and very little to eat. Historic records, however, suggest that early American fields of rye and wheat were once suitable nesting sites for a variety of grassland birds and Carpenter Road fields may illustrate one reason for the difference. So-called Round-Up Ready cereal crops that are drilled and then sprayed with broad-scale herbicides create fields that are so clean, so devoid of weeds, that they are entirely new agricultural landscapes. No 19th-Century farmer, no matter how fertile their soil, or however many times they cultivated, could match the ‘cleanliness’ of even the most average conventionally grown cereal crop today. Combine that with our ability to use heavy equipment to push out and even landforms to enable farmers to plant hedgerow to hedgerow explains why grassland birds are among the fastest declining guild of birds in North America. There simply isn’t enough habitat left in the Upper Midwest (or here in the Northeast where cereal crops are declining but still a valuable crop in some areas) to provide critical shelter and food.

As I walked through these wheat fields I wondered if this land would support grassland birds and I soon noticed Eastern Meadowlarks flushing from the field. A short distance later Savannah Sparrows foraged and I heard the insect zzzzzzz of a Grasshopper Sparrow.

The striking yellow breast and black chevron on the chest make the Eastern Meadowlark unmistakable. Photo: Mike Birmingham.

We still have a lot of upland meadows in the Hudson Valley, but the vast majority of those fields are intensively hayed with multiple cuttings. As we discussed in the Churchtown blog, this recent intensification of land use presents a level of disturbance that is incompatible with the needs of many grassland breeding birds. The Carpenter Road fields consisting of grains without herbicide and lightly used pastures do provide suitable levels of land use intensity and grassland birds are likewise present.

We must always be careful in ornithology to distinguish between the positive presence of birds and positive breeding outcomes. Grassland birds have an innate biological attraction to open fields regardless of the land use intensity and their mere presence does not guarantee that they are maintaining sustainable populations at that site since they could be attracted to large open areas that ultimately serve as traps where breeding fails. That said, in only a few moments of searching I was able to locate a few nests with eggs.

This Savannah Sparrow nest with eggs was located in the exact tussock of pasture grasses shown to the right. This nest existed in a field recently grazed by cows but the stocking rate was low enough to leave a few uneaten patches of vegetation used by this sparrow.

The Arthur’s Point silvopastures and tree nursery are unique habitats, with grass species similar to adjacent pastures but with greater structural diversity and the obvious hunting perches the young saplings provide. Early successional species such as Field Sparrow, Brown Thrasher, Common Yellowthroat, and Chipping Sparrow were common. Tree and Barn Swallows foraged over the meadow and Eastern Kingbird hunted from fence posts and trees.

Landscape structures like this are inherently ephemeral in the Northeast. Some disturbance — be it from mower or cattle — is needed to keep mature trees in check. This tension between field and forest can create a transitional habitat that is very productive for birds.

A Grasshopper Sparrow nested at the base of the white plastic electric fence post

In the short 20 minute walk up and around this hill, I counted two Grasshopper Sparrow nests and counted at least 8 birds, some possibly so-called hatching year birds that fledged at this location. This was a high-quality site for this species as several paired adults were preparing second clutches.

The Carpenter Road complex hosted about a dozen or so Grasshopper Sparrows in total which is likely the highest density for this species in Columbia County and among the highest I’ve ever found in the Hudson Valley!

Many of the farms I visited for this project have made some deliberate attempt to manage lands lightly or to leave some habitat unmanaged. In many ways these practices have led to higher-than-expected avian richness. Are there models contained in these farms that can be shared? Improved? Better studied? Will these models be enough to shelter and support birdlife as climate change mounts challenges even on protected land? Can conventional high-production farms be encouraged to leave more room for ecology as they are squeezed by market forces to become more efficient to survive? What does a farm of the 21st Century look like and who are the new stewards?

As many have written before, birds are a wonderful group of organisms for measuring, and educating others about ecological states. They are of a scale easily observed by amateurs, with memorable colors and sounds, and their populations in many instances wax and wane in rapid response to our actions. How can we coexist– or better, thrive — in same world?

Conrad captured this American Goldfinch during his end-of-summer visit to Carpenter Road