by Conrad.

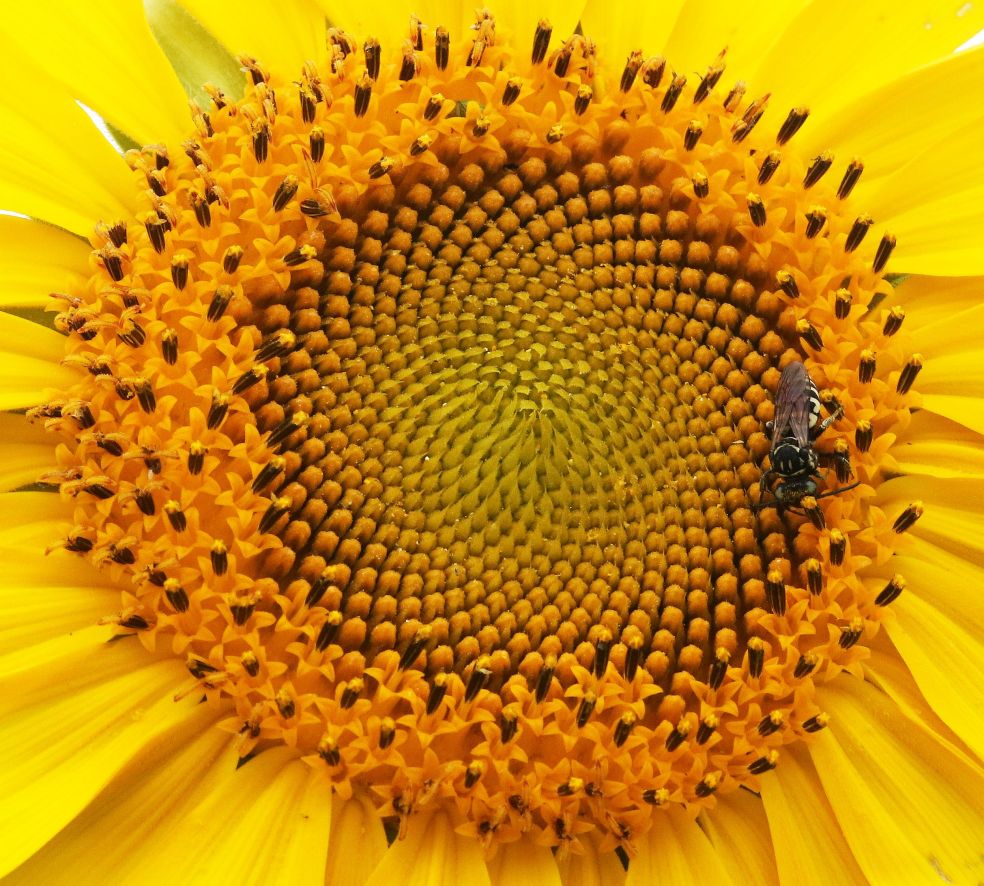

A Triepeolus bee about to get sucked into a Sunflower vortex (just kidding). These bees parasitize long-horned bees (see below).

INTRO

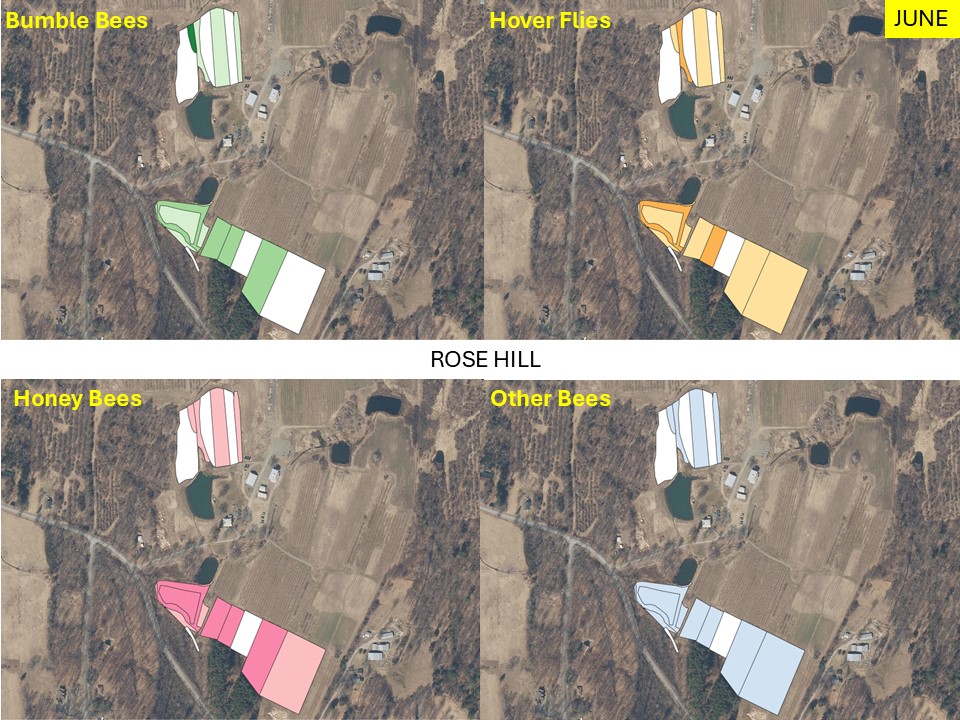

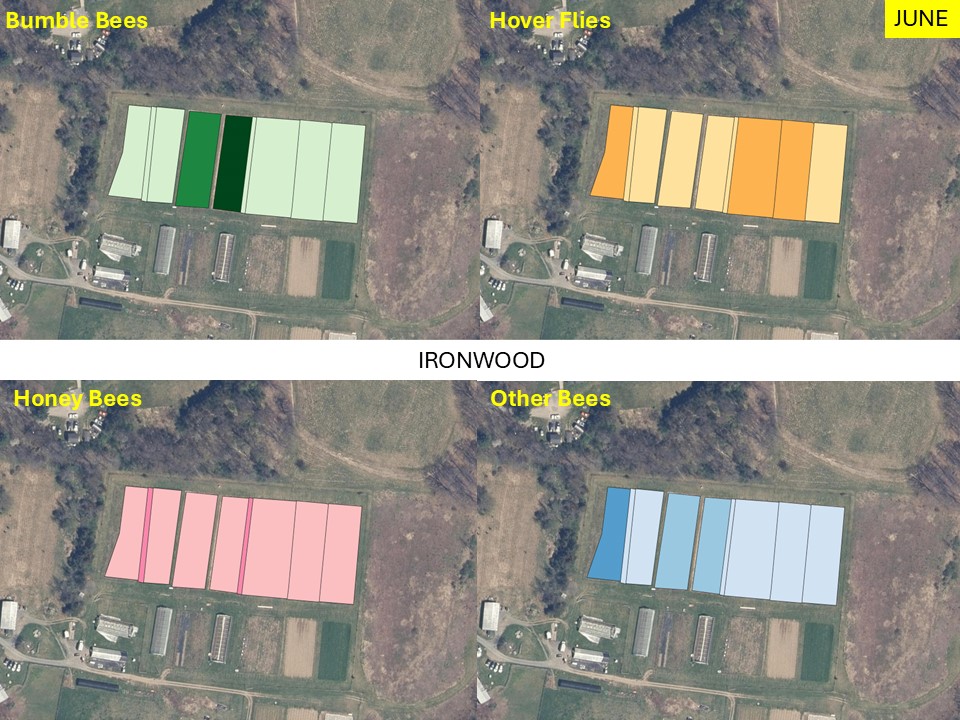

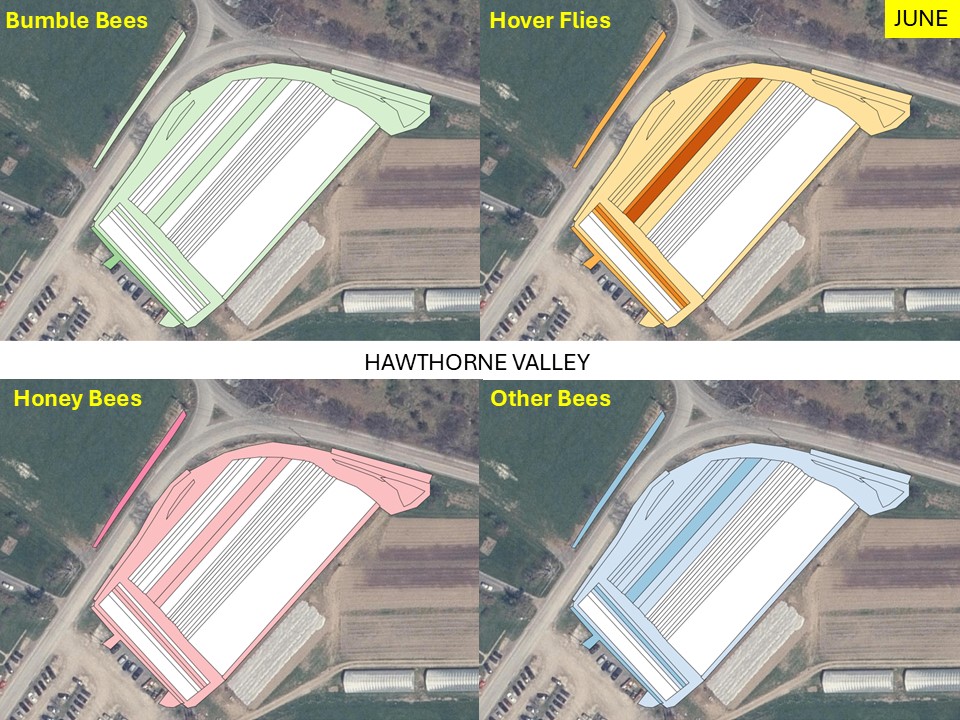

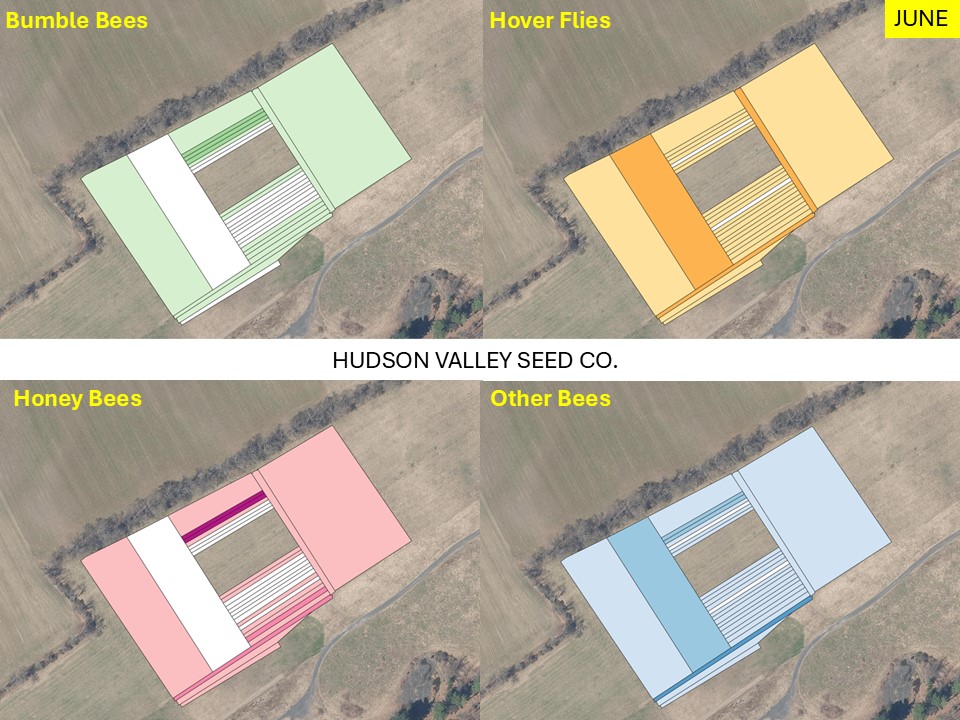

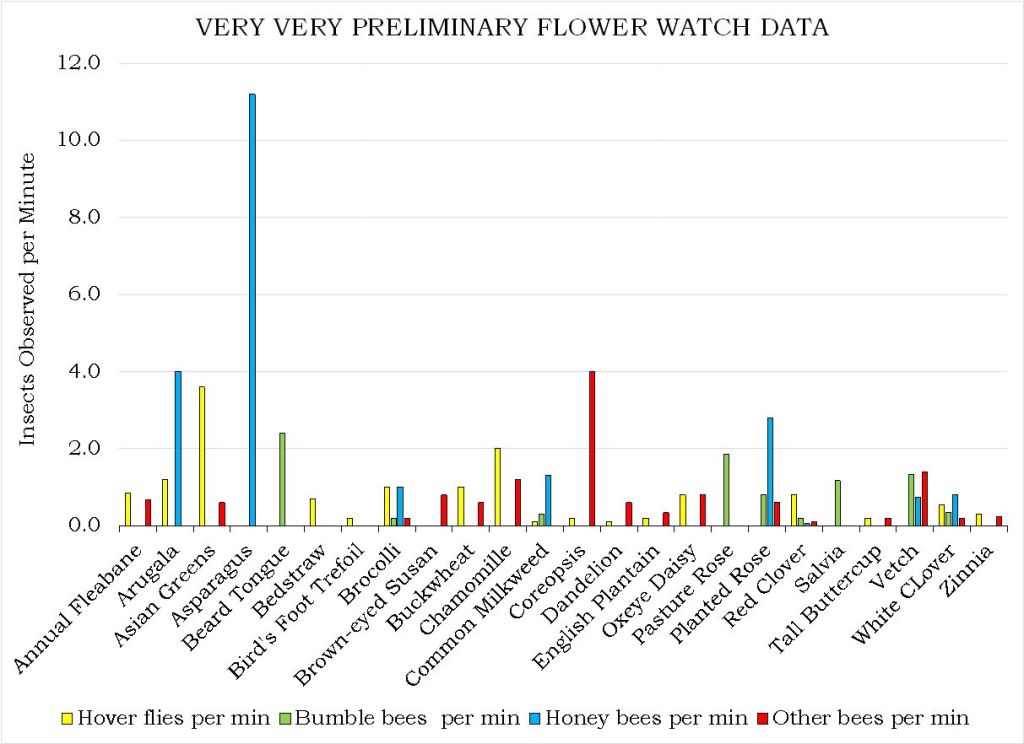

During the Summer, we collected data on the distribution and abundance of seeded and uncultivated flowers on and around nine different farms. We also gathered observations of bee visitation to those flowers. Future blog posts will explore this information in more mathematical detail in order to try to get a better understanding of the relative values of cultivated vs. uncultivated flowers in supporting bees. While the flower preferences of most of these bees are relatively well known, it is likely that such preferences are context dependent. In other words, like a person at a buffet, what is chosen depends on what else is available, so if our observations are useful, it is because they are derived from the actual context of regional farms and the flowers that are grown thereon, intentionally or incidentally.

A more skilled biologist than me could have conducted detailed visual surveys that gathered both behavioral data (that is, which flowers were visited?) and biodiversity data (that is, which bee species showed up?) However, I could not do both. Instead, I identified the relatively easy groups, such as Honey Bee, Bumble Bee and a couple of others, during the surveys. I took photos of the ‘unknowns’ when I could and then went back and tried to ID those bees from images. Most bees I saw were never photographed, and thus the collection of profiles that follow is in no way a complete list. In fact in Columbia County alone we have, summarizing across various years of work done by our program, found more than 150 species of bees; I registered less than 25 species during our observations this Summer. While some of this discrepancy may reflect the limited number of habitats and dates included in this project, it also reflects the shortcomings of my technique as a biodiversity study tool. Most biodiversity assessment studies use trapping of some form. Using photographs and visual tallies, I often can’t determine the species and below I’ll often talk at the broader scale of genera (genera are higher levels of biological organization than species; for example, wolves, coyotes and domestic dogs, while different species, are all members of the genus Canis).

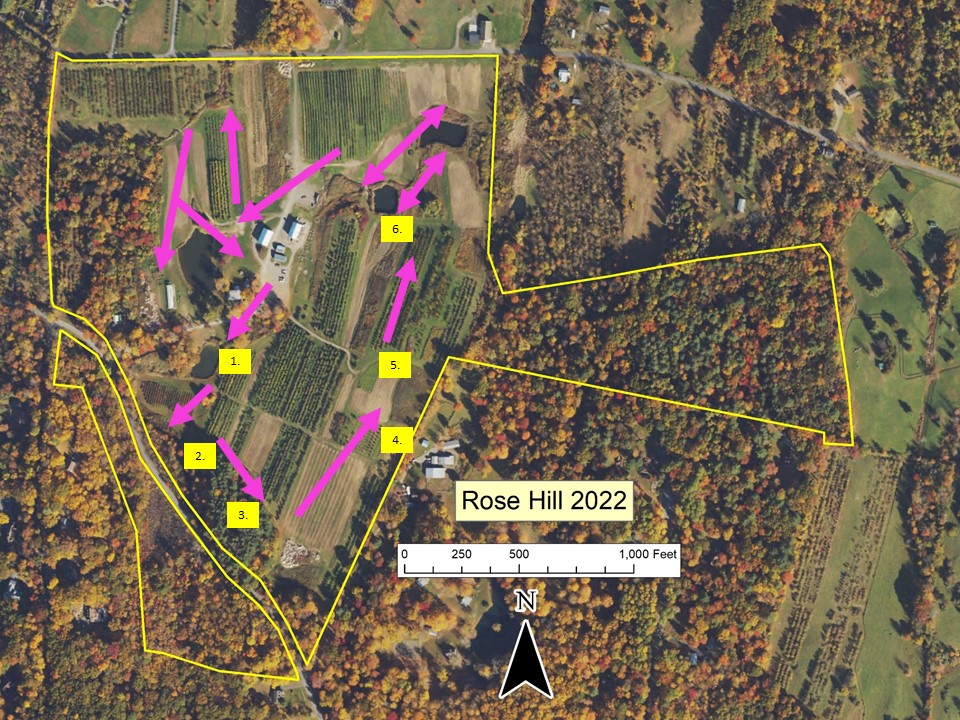

A seeded mix of Zinnia, Cosmos and Sunflowers with some true wild flowers to boot, in bloom at Rose Hill Farm. A variety of flower shapes and sizes can support a diversity of bees (and other flower visitors).

SOME BASICS

It’s important to remember that bees visit flowers for both nectar and pollen, with nectar generally being an energy source and pollen providing protein. Bees may be less picky about the flowers from which they collect nectar than those from which they gather pollen, but, when making observations, I did not try to distinguish pollen gathering and nectar slurping. While nectar and pollen can serve as food for the adults, they are often used to stock the nest (e.g., honey). To facilitate such brood provisioning, most female bees have special pollen-gathering hairs on their legs and/or the underside of their abdomens. Pollen gathering may be intentional (in order to stock the nest or to eat themselves) or unintentional (picked up incidentally when nectar sipping). The flower’s game is to lure bees with sweet nectar and/or appealing pollen and then encourage their pollen to hitch a ride to another, receptive female flower. Obviously, for flowers whose pollen is being gathered for juvenile or adult consumption, the flower’s ‘hope’ is that the bee will be somewhat messy, shedding at least a few pollen grains during its travels. Males do not gather pollen for the nest, and do not have the special, pollen gathering hairs of females. Nonetheless, fuzzy male bees do attract and share some pollen from the flowers they visit. Another set of bees – the pollen robbers (aka nest parasites) – don’t collect pollen for their own young. Instead, the females of these species count on usurping the nest of another bee species who has already done the work of pollen gathering.

One can think about flower visitors in various ways: as units of biodiversity to be tallied up to meet conservation goals, as winged workers pollinating diverse crops, as aesthetic elements adorning flowers, as nuisances ready to deliver a sharp sting to the unwary… During our project, we certainly tried to tackle the first two perspectives, albeit only partially: which flowers seem to support our native bees and thus benefit both insect conservation and crop (and other plant) pollination? Our tentative answers to this question will be forthcoming in our data analysis blog posting, but in this post I simply want to think of bees as other elements of life. How do they ‘solve’ that wondrous mystery of making a living and perpetuating their kind, largely regardless of what value we attach to them as currency of conservation or pollination? I’ll throw in a little bit of management and conservation speculation, but these profiles are primarily natural history snippets derived in good part from many of the publications and web sites listed at the end of the blog and contextualized by our own observations.

Squash Bee (top) and Not a Squash Bee (bottom, both at Blue Star Farm).

A FEW GENERALITIES FOR DESCRIBING BEES….

Bees have been categorized in different ways. One dimension is sociality. Most people’s first avatar of a bee is that of the Honey Bee. Relative to most of our other bees, the Honey Bee is, however, unusual. Specifically, its social system appears to be more complex and long-lasting than that of any of our other bees. The colony has distinct castes, can overwinter (and so must store up ample honey for the lean midwinter), and has complex communication amongst colony members, thereby focusing foraging and increasing its efficiency. Colonial life facilitates an effective nest defense and the protection of a large brood and food stores demands it, hence the origins of angry, stinging swarms to fend off possible nest destruction. Bumble bees and several other species also show some level of social organization, and as the profiles that follow may suggest, sociality happens in a variety of ways and to a range of degrees. Many bees do occupy the opposite social pole and nest solitarily – e.g., as single, isolate holes or cavities that only the mother bee provides for. Yet others fall somewhere in between in their sociality.

Another ‘dimension’ used to describe bee ecology is nest location. Some bees place their nests in holes in the ground, others use hollow plant stems, still others nest in rotting wood, and various others use natural or man-made cavities, or, even, clumps of grass. While not all species are 100% consistent in their choice of nesting substrate, generalizations are possible. As already mentioned, some bees don’t even make their own nests, instead parasitize the nests of other species.

Yet another descriptor commonly applied to bees is tongue length. This may seem a bit arcane and, aside from ant eaters and frogs, this trait might be relatively rarely considered elsewhere in the animal world. Its significance for bees is that it helps determine which bees can access the nectar of which flowers. A flower that buries its nectar deep down its ‘throat’ may only be usable by bees with long tongues. To an appreciable degree, certain flowers are evolutionarily designed for certain bees and deploy their nectar in ways that will encourage the passing bee to brush against pollen-bearing anthers and pollen-receiving stigmas. The depth of the flower is one aspect of flower architecture used to encourage this bee/pollen encounter. Although tongue length can vary dramatically amongst bees of the same size, it is also true that smaller bees tend to have shorter tongues. Admittedly, this is an overgeneralization – a small enough bee may be able to crawl down the flower tube to access deep nectar, while other bees short-circuit the system by slitting into the flower tube and so gaining more direct access to the nectar. While I report both tongue lengths and flower depths based on the literature, it should be noted that bee foraging is more complicated than an oil dip stick and measurements of the relevant lengths can be somewhat inconsistent, so don’t expect tongue length and flower depth to fully explain bee foraging, but it is a clue.

A Long-Horn (Melissodes) Bee displays its ample tongue while on a flower at Whistledown Farm.

SOME BEE PROFILES

I was going to gather all my profiles for one ‘glorious’ posting. However, creating these profiles has proved more time consuming than expected, my schedule has gotten more crowded than anticipated, and it dawned on me that sometimes a couple of shorter reads is more digestible than one long haul, so… I’m starting out with profiles of five relatively common bee groups: Halictus (a genus of sweat bee), Agapostemon virescens (a beautiful, easy-to-ID-on-the-wing species of sweat bee), Ceratina (a genus of little carpenter bees), Hylaeus (a genus of tiny, wasp-like bees) and Mellisodes/Eucera (a couple of closely related so-called ‘long-horn’ bees). Missing from this installment are Honey Bees, bumble bees, Lasioglossum sweat bees (i.e., those tiny critters who barely look like bees) plus a few rarer groups – meat for a second installment.

A Halictus bee pauses on a Daisy Fleabane at the Hudson Valley Seed Company.

Halictus – An Underappreciated Work Horse.

The most common species in this genus is Halictus ligatus and most, if not all, of our Halictus records may be of this species. This species is a darkish bee about the size of a large house fly with a hairy thorax and an abdomen banded by light hairs. It has oddly thick jowls. Somebody once said that these are markedly non-descript bees and that that, in and of itself, is a useful ID characteristic!

Halictus are common, geographically widespread bees who fly Spring through Autumn, and are reported to feed on a wide variety of flowers (as would be predicted by their long flight season). It seems to have long been common – when first described by pioneering entomologist Thomas Say in the 1830s, Halictus ligatus was stated to be “A very abundant species.” As befits their reported commonness and broad tastes, Halictus were found on eight of the nine farms we studied this year. In 2010, when we collected bees on 19 different farms around Columbia County, this genus was found at 13 sites, and it accounts for slightly over 5% of the bees in our regional bee collection.

It is a colonial or solitary ground nester. Colonies of up to ca. 200 individuals usually have a single queen bee, Halictus “worker” bees are able to reproduce and can replace the queen if she dies or can even fly off and establish their own colony if the mood strikes them. In other words, their sociality is facultative, meaning that if conditions suggest, a given species can either develop a colony or nest solitarily. Unpredictable weather and short growing seasons tend to favor solitary habits. As in bumble bees, the colony as a whole does not overwinter but the next year’s colony is founded by an overwintering female. Nests are described as drilled holes in relatively compact ground (such as along trails and road edges) and maybe re-used for various years. Some have said that Halictus also nest in rotting wood.

A Halictus bee on Chicory at Hawthorne Valley Farm.

This is considered to be a short-tongued species with a tongue length (ca. 3 mm) about half that of the Honey Bee. Our Halictus observations were spread more or less evenly across 16 different flower species. Amongst the seeded flowers, we found it on Bachelor Buttons, Black-eyed Susan, Cosmos, Feverfew, Oxeye Daisy, Strawflower, Sunflower, and Yarrow. Wild-growing flowers included Corn Chamomille, Daisy Fleabane, Field Bindweed, Grass-leaved Goldenrod, other goldenrods, Horseweed, knapweeds, and Sweet White Clover. Relative to average corolla length across all other flowers (ca.7.7 mm), the flowers visited by Halictus were short (ca. 4.0 mm). This genus of bee is reported to be an important pollinator of peppers, tomatoes, strawberry, turnip, apple, and watermelon, plus various cut flowers like marigolds and zinnias.

Agapostemon virescens on Black-eyed Susan at Hawthorne Valley Farm.

Agapostemon virescens – The Satisfying Sweat Bee.

Agapostemon virescens is part of a family of bees called “Sweat Bees”, because of the propensity of some members of this family to seek the salts on sweaty skin; Agapostemon itself, however, is said not to share this taste. I call this species ‘satisfying’ because it is both conspicuous (the iridescent emerald green is hard to miss) and, with their striped abdomens, the females of this medium-sized bee are easy to identify.

This is another relatively widespread, long-flying, common species. We noted it at 6 of the 9 farms this year and at 9 of our 19 farms in 2010. This genus is the third most common in our collection, accounting for a bit more than 15% of all specimens.

Agapostemon virescens nests in the ground, apparently often where the surface is relatively open. These bees reportedly can (but don’t have to) nest in groups, but when they do so, each female makes and supplies her own brood. Think apartment building with only one or a few entrances but many individual families inside rather than the more complex sociality of Halictus, Honey Bees or Bumble Bees. For this reason, Agapostemon are sometimes described as gregarious, rather than communal. Nonetheless, when found together, it is said that bees will take turns watching for predators and parasitoids, and will collaborate in aspects of nest repair. There are reportedly two generations during the season, with the first being all-female. It is bred females of the second generation who apparently overwinter.

An Agapostemon visits Canada Thistle at Whistledown Farm. Its ‘saddlebags’ are full of what is probably thistle pollen. If you get a chance, study the color of pollen carried by bees on different flowers – the variation amongst types of flowers can be surprising. For example, who knew Asparagus has day-glow orange pollen?

Agapostemon virescens bees are reported to forage at a wide variety of flowers, and we observed them on nine different species. Amongst seeded flowers, we saw them at Bachelor Buttons, Black-eyed Susan, Echinacea, and Sunflower; among wild flowers, they were seen on Elderberry, English Plantain, Knapweed, thistle, and White Clover. These are a mix of shallower and deeper flowers (average depth of visited flowers = 5.7 mm vs 7.4 mm for remaining flowers). Nonetheless, with a tongue length of about 3.7 mm, this is considered a short-tongued bee. Interestingly, the Sharp-Eastman photographic study of bees at Stone Barn Farm in Putnam County, noted that this was one of the few bees seen pollinating White Water Lily; during our farm work, we did not have a chance to test this observation! In terms of crop pollination, they are said to be especially common on carrots and cut flowers being grown for seed, but, as noted, they pollinate a wide variety of plants.

Ceratina feeding and mating on Feverfew at Stars of the Meadow Farm.

Ceratina – The Little, Motherly Carpenter Bee.

Ceratina are small bees with a blueish-green iridescence; they’re smaller than a small housefly but bigger than a gnat; perhaps think of them as a chubby long-grain rice kernels. While it’s hard to believe, their closest relative amongst our bees is apparently one of our largest bees – the Eastern Carpenter Bee, those massive, bumble bee-like creatures who drill into your outdoor woodwork. While Ceratina is somewhat inconspicuous, the teardrop shape of its tail end and the blue-green color mean that, with a little practice and good eyes, you can often ID it on the wing. The female (as well as the male) has a light patch on the ‘upper lip’. Ceratina also have relatively few pollen-collecting hairs on their legs or belly; some have suggested that they consume pollen on the flower and then regurgitate it in the nest, as Hylaeus (see below) is known to do.

We found this bee on seven of the nine farms we studied this year, and, in 2010, eight of the 19 farms visited. This genus accounts for 3% of the bees in our collection.

Ceratina bees apparently use their carpentorial skills to bore down the pith of stems such as those of raspberries, blackberries, roses and Queen Anne’s Lace (although stems have to be broken, so that there’s direct access to the pith). Despite often being considered solitary, they actually are reported to show some aspects of sociality – mothers tend young and sisters/daughters will help siblings and their mother. Rather than simply leave their eggs with provisions and ‘wish them luck’, mother Ceratina apparently not only guard the nest as the young develop but also help guard what then becomes the over-wintering hole (aka hibernaculum) of the emerged adult. Such a life history strategy, which depends on (or at least seems partially predicated on) an individual living for more than one year, is an unusual occurrence amongst bees.

Ceratina feeding on Daisy Fleabane at Little Seed Farm.

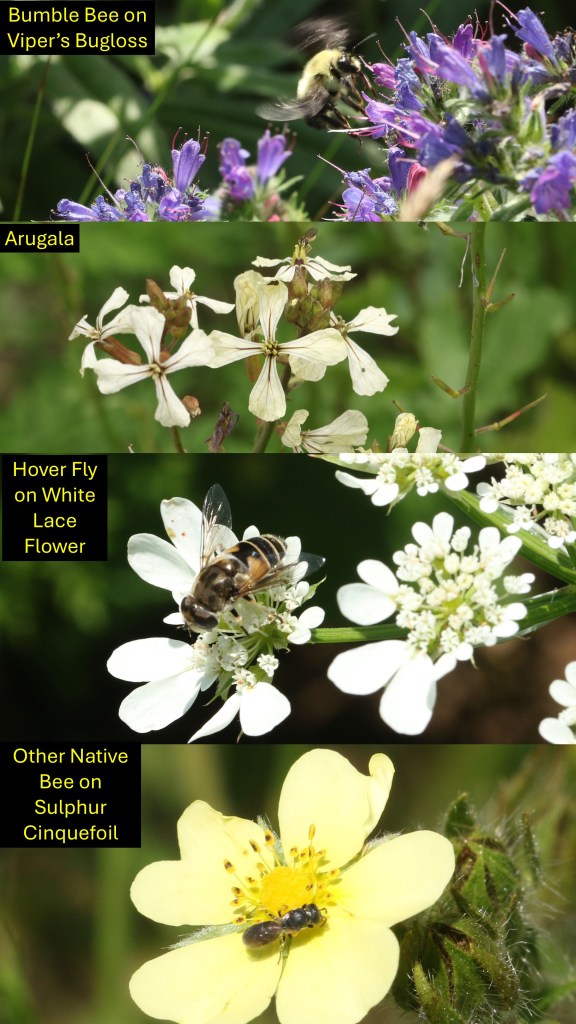

These are relatively common, widespread bees, who, like the preceding species, visit a variety of different flowers, indeed, we found this species to be widely distributed across 24 different kinds of flowers. Seeded plants included: Bachelor Buttons, Bird/Hairy Vetch, Black-eyed Susan, Butterfly Milkweed, Feverfew, marigold, Narrow-leaf Mountain Mint, Ox-eye Sunflower, Purple Coneflower, Snapdragon, Spotted Monarda, Garden Strawflower, White Coneflower, and White Gooseneck. Wild flowers visited by this species included Blackberry, Canada Thistle, Common St. Johnswort, Daisy Fleabane, Dandelion, Elderberry, English Plantain, knapweed, Sulphur Cinquefoil, and Viper’s Bugloss. They also visit roses and elderberry, both of which can be planted or wild. They are reported to be common pollinators of fruits, including apples, cranberries, blueberries, strawberries, and melons.

With a tongue length of about 3.7mm, Ceratina are considered ‘long-tongued’ bees (although on the short end of long!). The flowers they visited had the deepest average corollas of any of the bees so far considered: 7.5 mm vs. 7.2 mm for the depth of the remaining flowers. It seems ironic that the smallest bees so far considered should visit the deepest flowers, but, as mentioned, something else is also at play here – these bees are so small, that they sometimes crawl down into the ‘throats’ of large, deep-tubed flowers, i.e., they walk their tongues to the nectar.

Because they nest in old pithy stems, leaving standing stalks of goldenrod, raspberries, blackberries, elderberries, sumachs, and Queen Anne’s Lace can provide habitat. Cutting or breaking some of these at least a foot or so from the ground at the end of the first growing season will then ‘open the door’ and, assuming they are left undisturbed during the following growing season, these stalks could become valuable Ceratina nesting resources.

A Hylaeus bee on Common St. John’s-wort at Whistledown Farm.

Hylaeus – The Bee in Wasp’s Clothing.

Hylaeus are small, dark wasp-like bees. Their similarity to wasps is accentuated by their yellow-on-black markings, their elongated bodies, and their general lack of body fuzz. The yellow dashes along the inner side of the eyes on the female’s face look particularly waspish. These are part of a family of bees (Colletidae) who are popularly sometimes called “Cellophane bees”. This is not because they themselves are flimsy, but rather because they coat the inside of their nest capsules with a material somewhat like plastic wrap, which, as with sandwich wrap, seems to hold things together and deter fungus. This is all the more important given that the pollen-nectar mix that Hylaeus regurgitates to feed its young is a pretty soupy concoction (some authors talk about the larvae ‘swimming’ through it).

Hylaeus on White Lace Flower at Treadlight Farm.

We found this species on eight of nine farms we studied this year. In 2010, the genus was found during sampling on five of 19 farms. In our collections, it accounted for less than 2% of all specimens. Some bees are more readily counted visually than captured using netting or bee bowls, and these numbers may reflect that.

These are solitary nesters with no indication of sociality. Some say that they nest in the pith of plant stems (like Ceratina), although other sources just say that they nest in pre-existing holes (given their delicate jaws). Their nests are parasitized by Gasteruption wasps, which we recorded on the farm where we saw the most Hylaeus.

A Gasteruption wasp. This genus is said to parasitize the nests of Hylaeus bees. We consider it a good sign when we see native parasitic bees or wasps, because it indicates that the host population is robust enough to support them.

Hylaeus is considered a generalist in terms of the flowers it visits. During our work it was, far and away, seen most commonly on wild Queen Anne’s Lace, however we also observed it on seeded Anise Hyssop, Dill, Orpine, and White Lace Flower. Amongst wild flowers, it was seen on Common St. Johnswort, Galinsoga, Grass-leaved Goldenrod, Hedge Bedstraw, Horseweed, knapweed, Lady’s Thumb, Sulphur Cinquefoil, Tall Goldenrod (and close relatives), and a yellow Brassica. It was also seen on roses, which might be wild or planted. Hylaeus is a small bee with a short tongue (<1mm), so it’s not surprising that the average tube length of these flowers was short (4 mm) relative to that of the remaining flowers (7.7 mm). It is one of the bees for whom the wild, weedier, less showy flowers may provide an important resource.

Hylaeus may not be important crop pollinators, given that their habit of carrying pollen internally limits the likelihood that they’ll share pollen amongst flowers.

A Melissodes bee on Black-eyed Susan at Whistledown Farm. See also the earlier image of the bee displaying its tongue and of the Squash Bee (the closely related Eucera).

Melissodes and Eucera – Chunky, Funky, Long-horned Loners.

These two bee genera are closely related and considered together. This group includes several species, including the Squash Bee, our primary pollinator of squash plants. These are medium-sized (perhaps a bit smaller than a Honey Bee), generally fuzzy bees. The males in particular have long antennae (the “horns” of the common name). One description of bees stated that the males looked “a little like furry Chinese dragons” (which only really makes sense if you recall the long whiskers on the face of many such beasts). Many species have an orangish-yellowish hue, although one of our relatively common species is black with a pair of white butt spots.

The genus was found on five of the nine farms we visited this year. In 2010, our sampling on 19 different farms encountered it on five different farms. These genera account for nearly 6% of the bees in our regional collection.

A Two-spotted Melissodes (M. bimaculata) gathering pollen from Corn at Ironwood Farm.

Some Melissodes species can be especially common on Sunflowers late in the Summer. Indeed, some Sunflower beds we visited were almost swarming with these bees, sometimes with three or more to a flower. The Squash Bee is, of course, most common on… squashes.

Melissodes are considered solitary ground nesters given that a single female provisions a single nest hole, often in sandier soils. They will, however, sometimes nest in clusters, perhaps because of the limited availability of appropriate soils, and, occasionally, multiple females have reportedly been observed sharing a single nest opening, suggesting not a true colony but at least a shared front door. Melissodes diligently shut up their nests with packed soil. Nonetheless, the nests of these bees are parasitized by Triepeolus bees, a relatively large, distinctly marked creature, who follow a mother Melissodes back to the nest from a flower where they were foraging. They then descend the nest hole and lay their own egg by the pollen stash and egg of Melissodes. The resulting larva of Triepeolus then devours both host larva and its cache.

Melissodes tend to be late-season flyers and do seem to specialize somewhat by flower type, with our most common regional Melissodes seeming to favor Sunflowers. Our own observations supported this preference for Sunflowers, but they were also seen on a range of other flowers including, amongst seeded flowers, Bachelor Button, Black-eyed Susan, Blanket Flower, Brown-eyed Susan, Celosia, Coreopsis, Corn (!), Digitalis, Echinacea, Marigolds, Spearmint, Statice, and Zinnia. Among wild flowers, these bees were found on Chicory, Cosmos, Joe-Pye Weed and knapweeds. As this list suggests, many of these bees seem particularly fond of flowers in the Aster family, squash bees being an obvious exception.

Triepeolus on Sunflowers at Little Seed Gardens. A good place to get a nip of nectar and wait until your favorite host (Melissodes) happens by.

Melissodes and close relatives can be important crop pollinators for more than just squash and Sunflowers; they are also reported from cotton, alfalfa, muskmelons, watermelon, canola, and coffee, although given the relatively late-season flight times, they are not found regionally on spring-flowering fruits like apples.

Melissodes are considered ‘long-tongued’ bees, with a tongue length of 4-6 mm. The average depth of the flowers they visited (7.9 mm) was slightly larger than that of the flowers where they weren’t seen (7.2 mm).

CLOSING COMMENTS.

While we will develop these ideas further in later installments, even this small set of profiles illustrates some important points:

- The bee community includes more than Honey Bees and bumble bees. That’s probably a pretty obvious statement, but it can be easy to overlook the diversity of less conspicuous native bees out there ‘doing their thing’. Indeed, prior to the late 20th century few entomologists even considered the role of the wild bees in crop pollination!

- These are a diverse bunch, not only in terms of appearance but also in terms of behaviors – Are they social? Where do they nest? Which flowers do they favor?

- A diversity of bees needs a diversity of flowers to support them. Above we have noted the aster-favoring tendencies of some Melissodes, and the shallow inconspicuous flowers favored by Hylaeus. Likewise, at least in a farm situation, some bees are more or less reliant on seeded plants, while others prosper on the weeds.

- Importance to crops is variable and, of course, the agronomic utility of the bees depends, in part, on the crops one is trying to grow. It should be acknowledged that part of our goal is simply to conserve wild bees for their own sakes.

- Nesting location also varies and suggests various management techniques including sand piles and high-cut herbaceous stubble.

In the next installment of this blog, I plan to profile a few other bee groups. Claudia and I will then join forces for a data summary posting. We’re out of the field and at the desk…

USEFUL REFERENCES

iNaturalist (https://www.inaturalist.org) – This web site was a big help in identifying my bee photos; not only does it make a trained guess at what a creature is, it helps one link into a community of bee aficionados and experts.

Bee Watching (https://watchingbees.com) – Created by a couple of young bee experts, this web site gives tips for on-the-wing bee identification.

Wild Bees of New York (https://www.sharpeatmanguides.com) – This beautifully illustrated bee guide was created for Stone Barn Farms in Putnam County, but it works pretty well for us too!

The Danforth Lab at Cornell (https://www.danforthlab.entomology.cornell.edu/) – This is one of the State’s leading bee labs. See also https://cals.cornell.edu/pollinator-network/ny-bee-diversity and the book The Solitary Bees (2019) by Bryan N. Danforth, Robert L. Minckley, and John L. Neff.

The Bees in your Backyard: A Guide to North American Bees (2015) by Joseph S. Wilson and Olivia Messinger Carril. A really nice and useful introduction to our wild bees.

Common Bees of Eastern North America by Olivia Messinger Carril and Joseph S. Wilson. Drier than the previous volume and a field guide rather than an overview, but a handy reference.

The Melissodes Project (https://themelissodesproject.wildref.org/) by Frank Hogland, who provided welcome help identifying our bees in this genus.

The paper “Covariation among reproductive traits in flowering plants shapes their interactions with pollinators” by Jose B. Lanuza and colleagues was the source for most of my flower depth measurements (https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1365-2435.14340). This was supplemented by the work of Franziska Baden-Böhm and colleagues, “The FloRes Database: A floral resources trait database for pollinator habitat-assessment generated by a multistep workflow”, available at https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1365-2435.14340 and by the work of Barry A. Prigge and Arthur C. Gibson, A Naturalist’s Flora of the Santa Monica Mountains and Simi Hills, California, as accessible from https://www.smmflowers.org/mobile/ANF-other/ANF_Descriptions_TOC_Mobile.htm. (Looks like a great flora, almost makes me sorry not to live there!)

Bee tongue lengths were taken from the work of Daniel P. Cariveau and colleagues, “The Allometry of Bee Proboscis Length and Its Uses in Ecology”, available at https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0151482