by Claudia (with Josie)

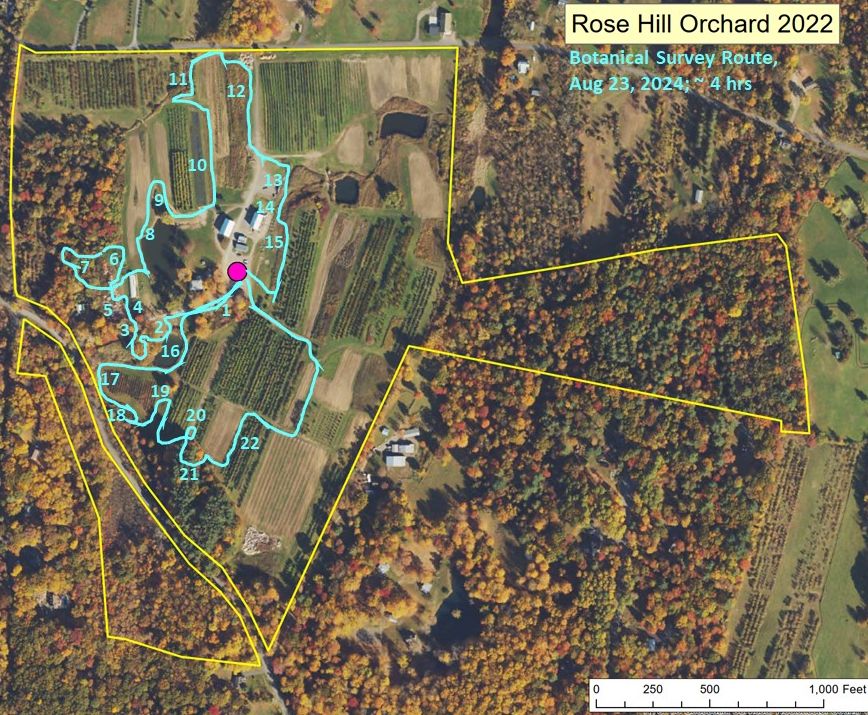

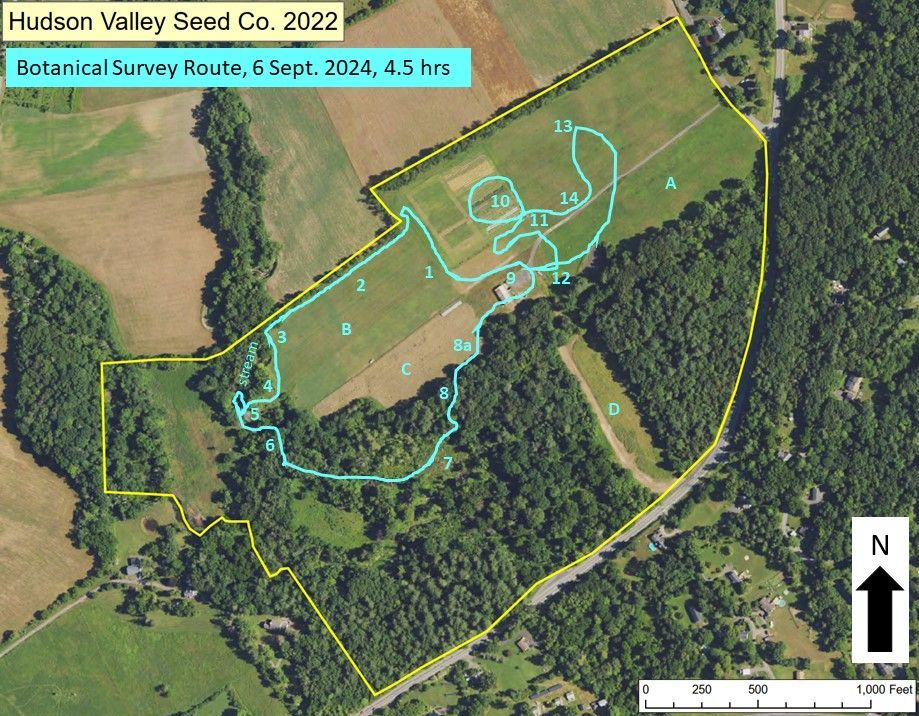

On 6 September 2024, we spent ~ 4.5 hours documenting the wild-growing plants of a cross-section of habitats at the new site of the Hudson Valley Seed Company on Airport Road in Accord. The following image highlights the approximate route taken and numbers observation points we will refer to throughout the blog.

We began our survey along the west and north edges (#1 & #2) of a large tilled field. We found the usual field edge/hedgerow mix of common native and non-native plants. Half of the 20 invasive species recorded on the property were also represented in this area: Oriental Bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), Eurasian shrub honeysuckle (Lonicera morrowii or L. bella), autumn-olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), Japanese Barberry (Berberis thunbergii), privet (Ligustrum sp.), Winged Burningbush (Euonymus alatus), Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), Japanese Stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum), Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris), and Canada Thistle (Cirsium arvense).

We also found an abundance of the native (but sometimes over-enthusiastic) spiny vine, Common Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia). Its fruits ripen in the autumn and somewhat resemble grapes, and some people consider them edible (I have never tried them). However, there are amply references on the internet of people eating the tender shoots in spring, and also using the dried roots to make a starchy powder used in a variety of ways.

These fuzzy little seed heads belong to another native vine, Virgin’s Bower (Clematis virginiana). It is related to buttercups and, like many plants in that family, has secondary compounds that are poisonous/medicinal (depending on dosage).

Several tall Bitternut Hickory (Carya cordiformis) trees could easily be identified by their thin-husked fruit with four “seams.” The related Shagbark Hickory (C. ovata) has a much thicker husk and Pignut Hickory (C. glabra) does not have the pronounced “seams.”

Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) was also present in the field margin (#3) and down near the stream. In the southern field margin (#8a), we also found Butternut (Juglans cinerea). These two, closely-related native species of walnuts are easily distinguished when fruits are present: the fruits of Black Walnut are almost round, while those of Butternut are more elongated (think of a stick of butter!).

At the west end of the big field, we found an unmowed meadow sloping down to the stream. The dry part of this meadow (#4) was dominated by two invasive species, Japanese Stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum) and Brown Knapweed (Centaurea jacea; purple, thistle-like flowers visible on the bottom right in the image).

However, there was also a nice clump of the Fragrant Rabbit-tobacco (Pseudognaphalium obtusifolium), as well as a smattering of other native species, including Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) and one of the common oldfield asters, possibly Pringle’s Aster (Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei).

On the dry slope leading down to the stream, we also discovered a turtle egg that had been dug out of its underground nest and been preyed upon. We don’t know which turtle species had made the nest here, but the stream and adjacent floodplain forest might be home to the rare Wood Turtle.

Further down the slope and closer to the stream, the vegetation was taller and indicative of a wet meadow (#5), including Broad-leaved Cattail (Typha latifolia), Woolgrass (Scirpus cyperinus), and Tall Goldenrod (Solidago altissima). There were also large patches of the invasive Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris),visible in the foreground of this image.

The stream had small gravel bars with a mix of native and non-native plants, including Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica), visible in the background of this image.

This wetland (#7), which had a mosaic of shrub swamp and wet meadow, was a bit difficult to move through, but harbored some botanical treats, including many plants of Rough-leaved Goldenrod (Solidago patula), visible in the foreground, one of our less-common goldenrods, which seems to be a good indicator for calcium-rich wetlands.

We also stumbled across the Turtlehead (Chelone glabra) in full bloom. The leaves of this species are the preferred caterpillar food of Baltimore Checkerspot butterflies.

Another exciting find in the wetland was this Groundnut (Apios americana) with fruits. While we occasionally see flowers of this uncommon wetland plant in the Hudson Valley (see blog about the plants at Rose Hill Farm posted on 17 November 2024) it seems to rarely produce seeds in our region. According to Wikipedia, this species has diploid and triploid plants, with seemingly no big difference in their appearance. Only diploid plants (which tend to be more common south of our region) can produce viable seeds, while triploid plants (more common in our region and north of here) rely on vegetative reproduction.

The potato-like tubers of Groundnut are edible and have a long history of use (and likely cultivation) by native Americans.

This is a more shrubby part of the wetland with a Common Winterberry (Ilex verticillata) in the foreground.

Quite common among the shrubs was Poison Sumac (Toxicodendron vernix), which is an upright-growing plant closely related to Poison Ivy (T. radicans) and has the same rash-inducing urushiol resin. In contrast to our other sumacs (Rhus spp.), which have red berries, the berries of Poison Sumac are white like those of Poison Ivy.

Like the Rough-leaved Goldenrod mentioned earlier, Poison Sumac is considered a good indicator for calcium-rich wetlands.

The northern edge of the wetland supported patches of Cinnamon Fern (Osmundastrum cinnamomeum), seen here as yellowish clumps, mixed with a tall, rhizomatous (non-clumping!) native sedge, Lake Sedge (Carex lacustris), and the ubiquitous, invasive Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria).

The edge between the upland forest (#8) and the wetland (#7) is not a straight line. In this picture, a “finger” of low ground with wetland vegetation reaches between two areas of upland forest on higher ground.

In the edge to the field (#8a) we found the before-mentioned Butternut tree.

This field edge also had a small patch of an interesting native plant not seen anywhere else at the Hudson Valley Seed Company, nor at any of the other farms we have surveyed this summer. Flat-topped White Aster (Doellingeria umbellata) is a northern species, common in the Adirondacks and in northern New England, but we rarely see it in the Hudson Valley south of Troy.

Near the buildings (#9), we noticed a small “island” of native plants in the vegetation that was otherwise dominated by common European plants.

Early Goldenrod (Solidago juncea), Gray Goldenrod (Solidago nemoralis), and Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) might have been seeded here or might have come in on their own. These three species often are found growing together on dry soil.

Yellow and Giant Foxtail (Setaria pumila and S. faberi) were very common in the recently disturbed soil around the new building. Yellow Foxtail has upright, yellow-brown spikes of seeds; Giant Foxtail has light green, nodding spikes.

Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca; big leaves in picture below) and Indian-hemp (Apocynum cannabinum; small leaves in picture below) were two native plants growing between the cultivated rows (#10). They both belong to the same plant family and have white latex. Both produce flowers that are visited by many pollinators.

The strip of meadow along the north edge of the driveway (#11) had a lot of the native warm-season grass Purple-top (Tridens flavus), while the large hayfield (#13) beyond was dominated by the European cold-season grass Orchard Grass (Dactylis glomerata).

It was nice to see that the Orchard Grass-dominated meadow (#13) had some Common Milkweed mixed in. The fields A, B, and C were all recently-tilled and bare ground during our visit. Field D was an unmowed old field dominated by goldenrods, interspersed by Purple Loosestrife.