by Claudia

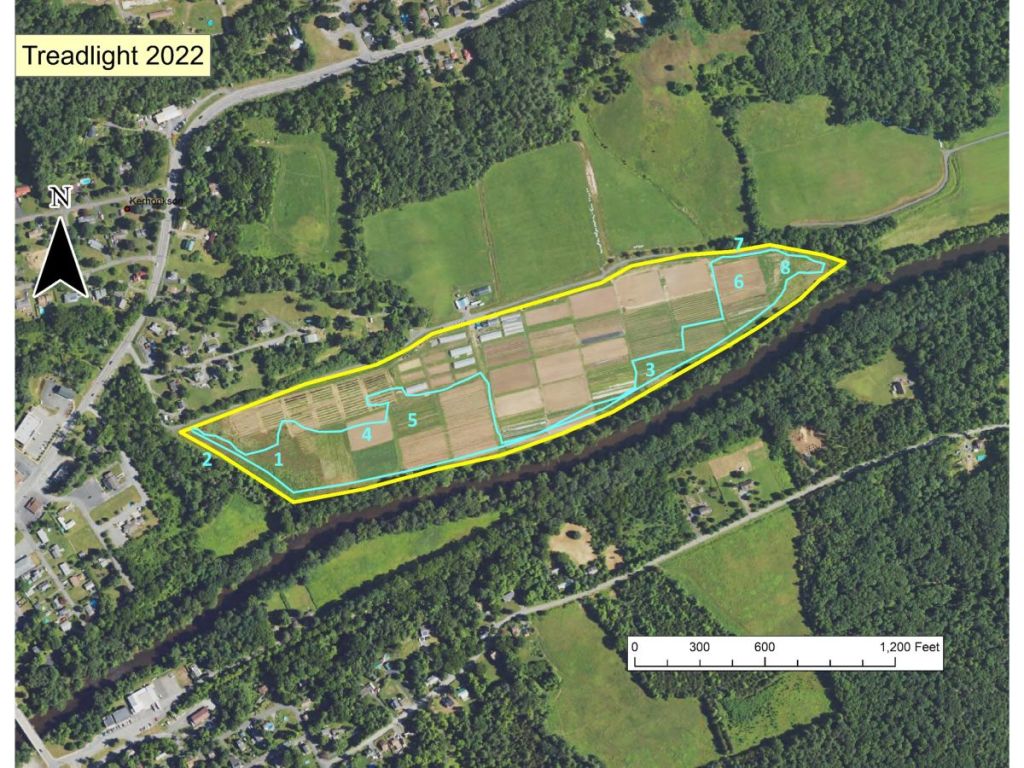

I visited Treadlight Farm in Kerhonkson on 4th Sept. 2024 to survey the wild-growing plants inside the fenced area outlined in yellow on the aerial photo below. The sky blue line indicates the approximate route of my four-hour walk-around. Numbers refer to locations mentioned below.

As Conrad has already described in the last posting, Treadlight Farm mainly grows cut-flowers and also produces plugs (mostly of native wildflowers). The farm operates on leased land that has a long history of farming and few semi-wild habitats are found within the farm’s fence. Not surprisingly, the wild-growing plants in the flower beds were largely the usual cast of regionally-common, annual, tilled-field weeds, including Common Ragweed, Daisy Fleabane, Horseweed, Lamb’s-quarters, Crabgrass, and foxtails.

At the west and east end of the farmland are old fields, largely composed of perennial species, both native and non-native. Those old fields harbored at least five species of goldenrods and seven species or varieties of asters, all native. The “grassy” matrix at the west end (#1) was dominated in late summer by the non-native grass Hard Fescue (Festuca trachyphylla), but also included the native Path and Soft Rushes (Juncea tenuis and J. effusus).

At the time of my visit (4th Sept.), the asters were just starting to flower, but the goldenrods were already in full bloom. In the image below, the golden yellow flowers of Tall Goldenrod (Solidago altissima) contrast beautifully with the purple flowers of New England Aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae). Tall Goldenrod (also often referred to as Canada Goldenrod) is one of four very common, rhizome-forming, old field goldenrods in our region. We know of 11 other goldenrod species in our area, all less common than the four old field species, and associated with other habitats, such as dry meadows, wetlands, and even forests. All our goldenrods are native species and—as a group—provide resources to a dazzling variety of insects, who visit the flowers for nectar and pollen, eat the leaves, bore in stems and roots, form galls, or wait for prey in the flowers.

Nearby, Early Goldenrod (Solidago juncea) was still in bloom. This is a species that does not form rhizomes and does not grow in dense colonies. In fact, it does not compete well with the more aggressive goldenrods on fertile and moist soils. Therefore, it is usually found on somewhat dryer, less nutrient-rich soils. This is one of the earliest-flowering goldenrods, it usually has a basal rosette of leaves, as well as small clusters of leaves in the axils of the stem leaves.

A strip of herbaceous vegetation has been maintained along the outside of the deer fence (#2), forming the edge between farmland and wooded riparian corridor along the Roundout Creek. This strip harbors some of the same species as the old field, but also some species associated with the riparian corridor, such as Sensitive Fern (Onoclea sensibilis), Deer-tongue Rosette Grass (Dichanthelium clandestinum), and a species of native sunflowers described below. Unfortunately, invasive plant species, including abundant Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) and Japanese Stilt Grass (Microstegium vimineum) also thrive in this occasionally mowed strip.

I was excited to find several patches of Thin-leaved Sunflower (Helianthus decapetalus) on both sides of the deer fence along the southern edge of the farm fields (#3). This beautiful native wildflower tends to grow in semi-shaded riparian areas and occasionally along roadsides. I would think that it could also find its place in native plant gardens and seeded wildflower meadows, but its seeds are still hard to find in seed catalogues. Would this be a candidate for the production of eco-type seeds and plugs?

The next image shows a flower head of a Thin-leaved Sunflower in its prime. Note how this flower head is composed of two types of flowers: the large, petal-like ray flowers visually attract pollinators, while the small, star-shaped disk flowers at the center focus their energy on pollen, nectar, and—eventually—seed production. Note how the disk flowers mature first around the outside of the disk. The dark columns emerging from the open disk flowers bear the pollen. The flowers at the center of the disk are still green flower buds.

The following collage illustrates a sequence of flower heads at different stages of development (clockwise from top left): (1) the young flower head is mostly defined by its green bracts, the disk and ray flowers are still developing; (2) a flower head just coming into bloom, with some—but not all—disk flowers spreading and receiving pollen; (3) a flower head at or just past the peak of its blooming period seems to have spent all its pollen, but might still be receptive for pollen brought in from other plants; (4) this flower head has dropped its ray flowers and is now ripening its seeds, one per star-shaped disk flower.

Returning from the riparian corridor back towards the center of the farm, a fallow field (#4) sports a riot of weeds, including the native Daisy Fleabane (Erigeron annuus; white flowers), and the non-native grass Yellow Foxtail (Setaria pumila; orange, upright spikes) and an unusually large smartweed (probably Persicaria longiseta; drooping, pink spikes).

Nearby, I found another smartweed, the non-native Lady’s Thumb (Persicaria maculata), which also seemed particularly robust.

In these beds (#5), a variety of native wildflower species were cultivated. They included several mountain-mints (Pycnanthemum spp.), asters (incl. Symphyotrichum laeve), and Joe-Pye-weed (Eutrochium sp.). However, I did not attempt a complete inventory of these cultivated flowers.

The following collage shows three different species of mountain-mints cultivated at Treadlight Farm (from left to right): Narrow-leaved Mountain-mint (Pycnanthemum tenuifolium), possibly Hairy Mountain-mint (P. cf. verticillatum), and possibly Blunt-leaved Mountain-mint (P. cf. muticum).

The native One-seeded Bur-cucumber (Sicyos angulatus), a wild cucurbit, was mingling with the Joe-Pye-weed.

Not many native plans were thriving in the rows of dahlias (#6).

At the northeastern corner of the farm fields, I found a small strip of old field/wet meadow (#7), which harbored some Purplestem Asters (Symphyotrichum puniceum), not seen anywhere else at TFreadlight Farm and possibly quite a few Willow-leaved Asters (S. praealtum). The latter species was not yet in bloom, so I am not 100% certain of its identity.

A pink (more typical would be lavender) flower head of Purplestem Aster in lovely contrast with the yellow flowers of Flat-topped (a.k.a. Grass-leaved) Goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia).

Three different native asters were common in the old field in the east corner of the farm (#8). These small-leaved, white-flowering species are notoriously hard to identify, but I suspect them to represent (from left to right): Calico Aster (Symphyotrichum lateriflorum), Pringle’s Aster (S. pilosum var. pringlei), and Awl Aster (S. pilosum var. pilosum).

I did not find many unique native plants at Treadlight Farm—a fact easily explained by the relative homogeneity of habitats within the farm’s fences: there were no waterbodies, no substantial wetlands, no rock outcrops, and basically no woody vegetation. Therefore, the Farm supported mostly habitat generalists, which were also found at some of the other farms.

However, the old field patches at the west and east end of the farm, as well as the fence line did support more species of native asters than I had found at any of the other farms this summer. In addition to the species already mentioned above, Lance-leaved Aster (Symphyotrichum lanceolatum) was probably the most common of all asters in many places along the fence line and in unmowed interior areas, and Heart-leaved Aster (S. cordifolium) occurred mostly along the southern fence line.