By Claudia & Conrad.

INTRODUCTION: Basic Premises.

It is perhaps useful to start from a few basic facts:

- While certainly not necessary for all crop production, many crops require pollinators for the production of the crop itself and/or the seeds of that crop and/or are assisted by the biocontrol provided by the aphid-feeding larvae of wasps and hover flies who, as adults, feed on nectar.

- With roughly 450 species of bees known from New York, plus numerous other flower visitors including many wasps, hoverflies and various butterflies and moths, flower visitors form an appreciable part of our insect biodiversity.

- The relationships amongst various flower visitors and various flowers illustrates the maxim, “different strokes for different folks”. In other words, the flower preferences of different bees (not to mention other insects) can vary markedly amongst species, reflecting varying needs and offerings (including the fit of flower and insect morphological traits, coincidence of flight and flowering seasons, and the satisfaction of intricate insect nutritional requirements), co-evolutionary histories, and coincidental preferences.

- Our own species has clear aesthetic flower preferences, which regularly do not align with those of all flower visitors.

- The flower offering of a given farm is composed of several groups of flowers: those flowers intentionally planted for cut flowers and/or insect habitat, the flowers of crop plants where fruits are the main crop (e.g., tree fruits and berries, but also tomatoes, peppers, eggplants, squash, cucumbers, etc.), the flowers of crops (including cover crops) wherein the flowers are of little importance to production, and true wild flowers (sometimes considered weeds) composed of those native and non-native flowers that grow on farms in cultivated beds, as low blooms in cut drive strips, or as wild growth in edges, fallows and other nearby lightly-managed habitats.

- By and large, human attention tends to focus on the intentionally grown flowers, with little notice paid to the potential ecological value of wild-growing flowers, except where they are considered weeds.

- Finally, as a result of all of the above, a farm’s pollinator and biocontrol community and its overall insect biodiversity are shaped by a variety of intentional and unintentional flower management actions, often based on economic or aesthetic criteria and sometimes only partially informed by ecological considerations.

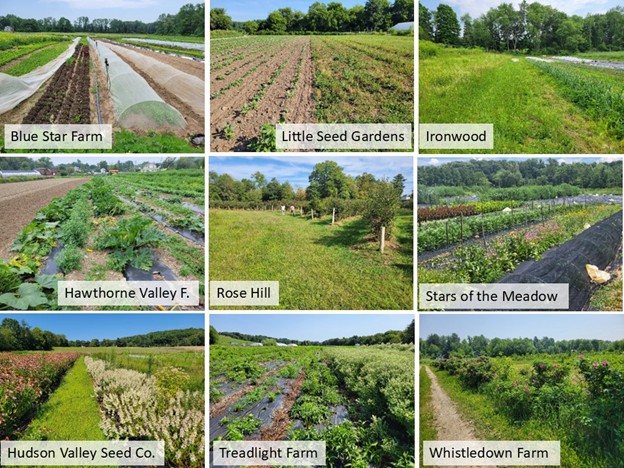

Starting from these premises, our work during the summer of 2025 sought to better understand the distribution and insect use of flowers on nine different farms in the Mid-Hudson Valley. Which species of flowers occurred on these farms during the growing season? Were they native or non-native? Were they wild-growing or cultivated? Where did they occur on the farm? Which insects used each of the different flowers? And, ultimately, how might a farm’s flower management be tweaked to enhance the community of flower-visiting insects?

WORDS OF CAUTION: We’re Hardly Perfect.

Several words of caution regarding the short-comings of our work are appropriate.

First, while we focused on summer flowers (June-mid Sept.) within our study areas as a key resource for flower-visiting insects, mid-season flower-availability is definitely not the only factor affecting their success. Other influences include the degree of freedom from conventional or organic pesticide exposure (see here for Xerces summary of the impacts of organic pesticides), availability of overwintering and brood sites (and, in the case of parasitoids, of larval hosts), the availability of flowers during the “shoulder seasons” (when we didn’t do surveys), competition and predation by other co-occurring animals, and flower availability outside of our study areas.

Second, we only looked at nine farms and made only three visits to each. Flower preferences may well vary in relation to flower maturity, time of day, weather, and the life-history stage of the insects. Also, each farm is different and if one wants to extract generalities, then the more farms the better. These are intricacies our observations did not address. Practicality more than optimal study design dictated the number of farms and outings.

Lastly, practicality also determined what we could do during each outing. The scale and nature of our study was limited by the self-imposed restriction of not spending more than a half day at each farm. This meant that we only mapped flowers on a portion of each farm and used quick and relatively subjective flower abundance estimates. Perhaps most importantly, it meant that we were satisfied with relatively crude taxonomic identification of the various flower visitors. While it was possible to identify the species of several flower visitors on the wing during surveys and to name several more from photographs, we did not undertake the specimen collection that would have permitted more precise identification of most insects observed. Instead, we field-identified most flower-visiting insects only to general groups, such as bumble bees, hover flies, wasps, etc. (see below for all taxonomic categories used).

All these cautions mean that, at best, our flower favorability maps show the potential for a given patch to support a particular group of insects from the perspective of floral offering. If we compare our predicted flower favorability ratings for an entire farm with the observed rates of flower visitors at that farm on that date, the relationship is scant. The best that can be said is that farms with substantially below average flower offerings do seem to have somewhat lower visitation rates than those with more favorable flowers, but that boost seems to peak pretty quickly. This implies that either our higher assessments are too rough or that once flower visitors have the minimum flower offering that they need, then other factors such as nest sites become limiting and so more flowers don’t boost populations.

In sum, if you read any of this and think, “Geesum, this study would have been better if they had ….”, then you’re probably right. Please do share such thoughts however, maybe we can do better the second time around!

METHODS: What We Did.

What did we do? We worked in parallel with Claudia surveying the flowers and Conrad observing the flower visitors.

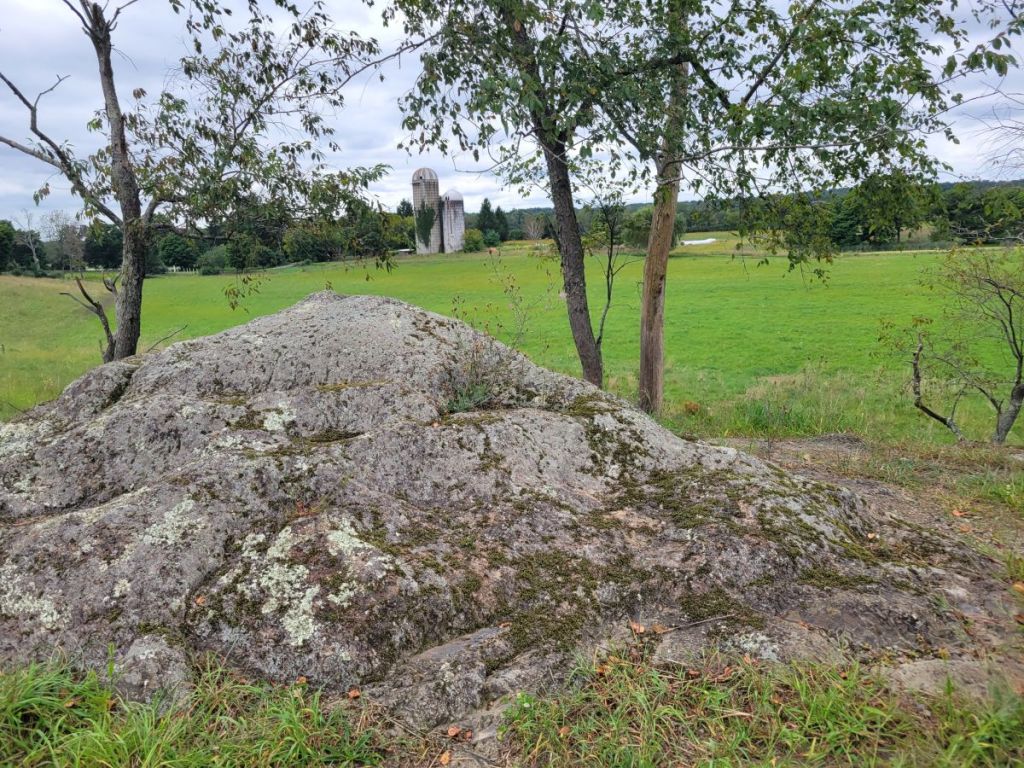

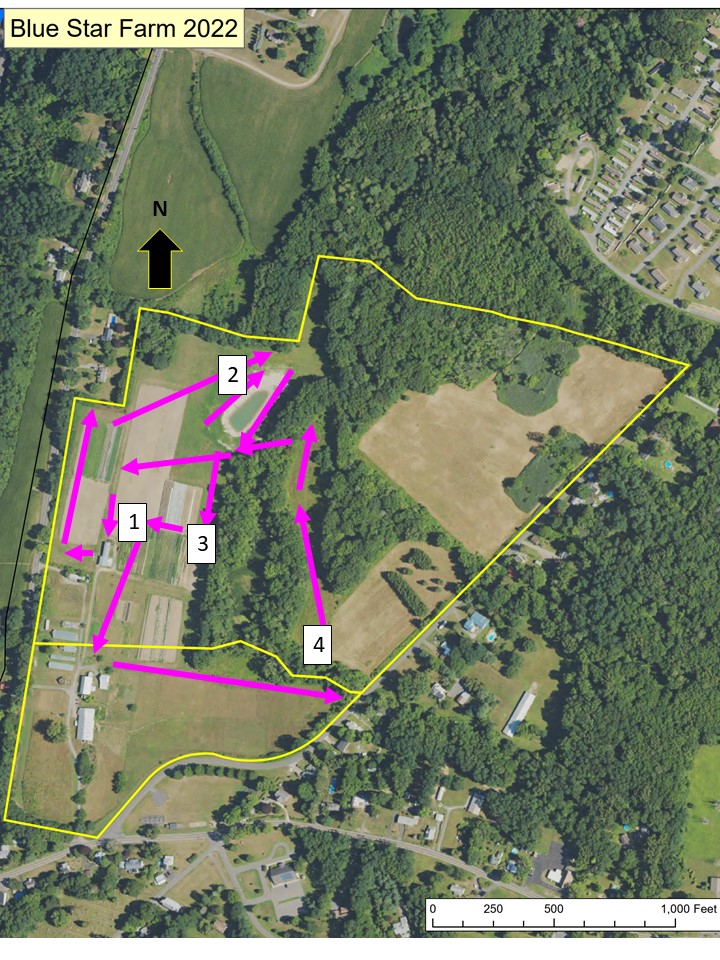

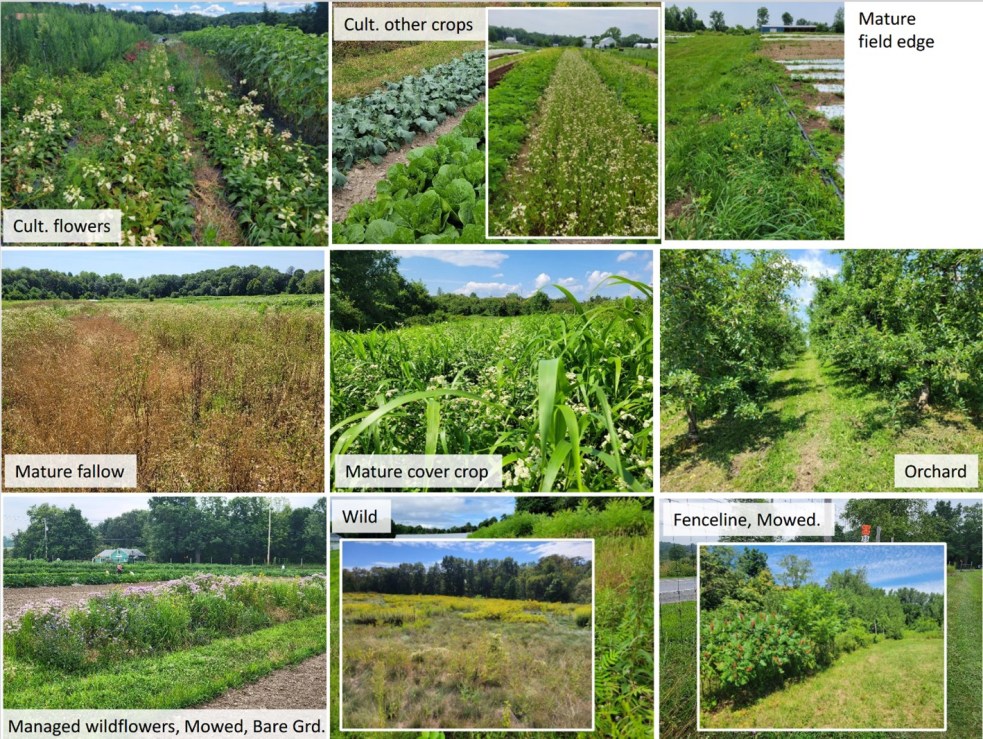

Flowers. After determining the study area at each farm, Claudia delineated survey units and classified them by general management regimes/habitat types. These included the categories: bare ground/plastic; cultivated flowers/woodies; cultivated, other; managed wildflowers; mature fallow; fenceline; mature cover crop; mature field edge; mowed; wild (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Examples of the management regimes represented in our study

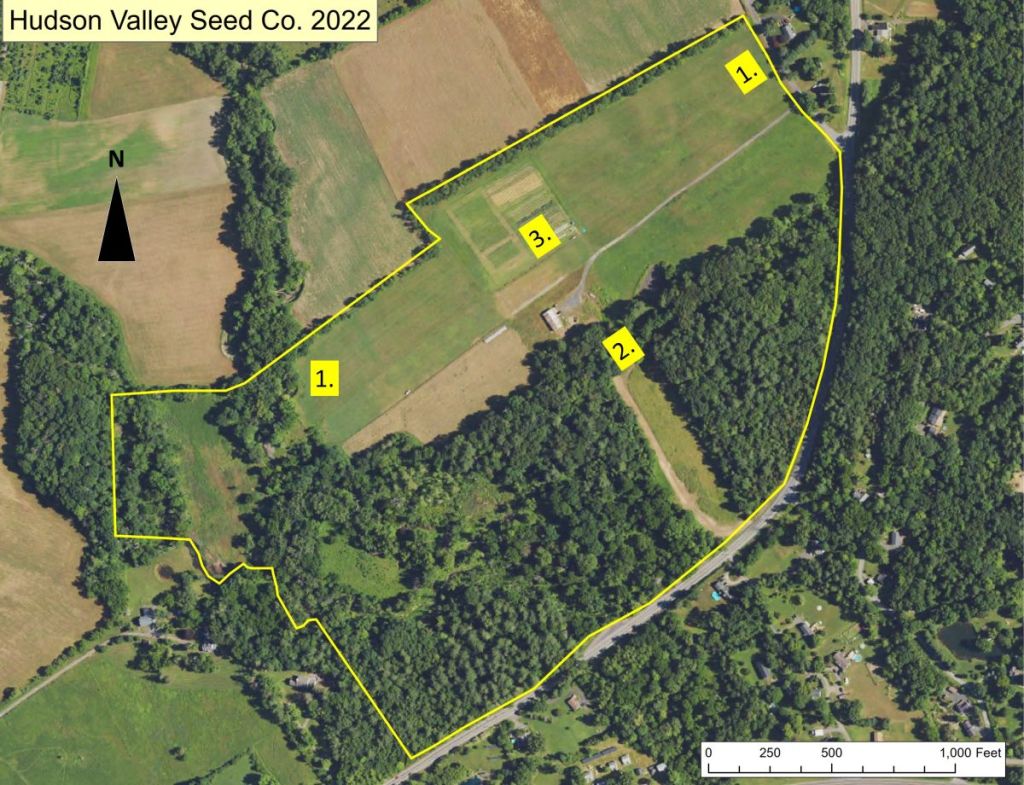

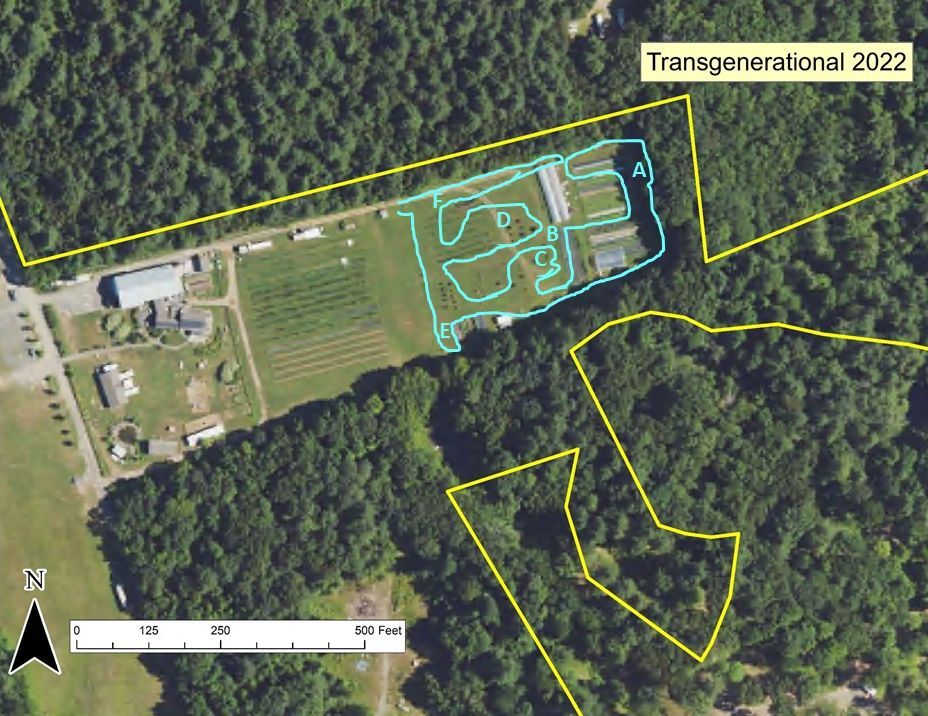

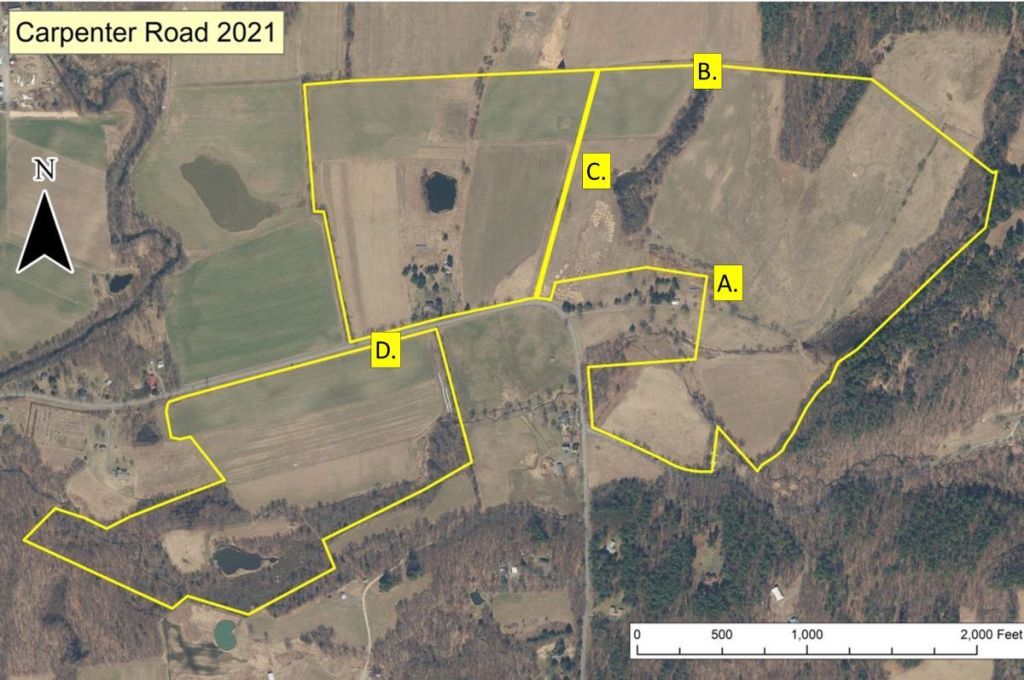

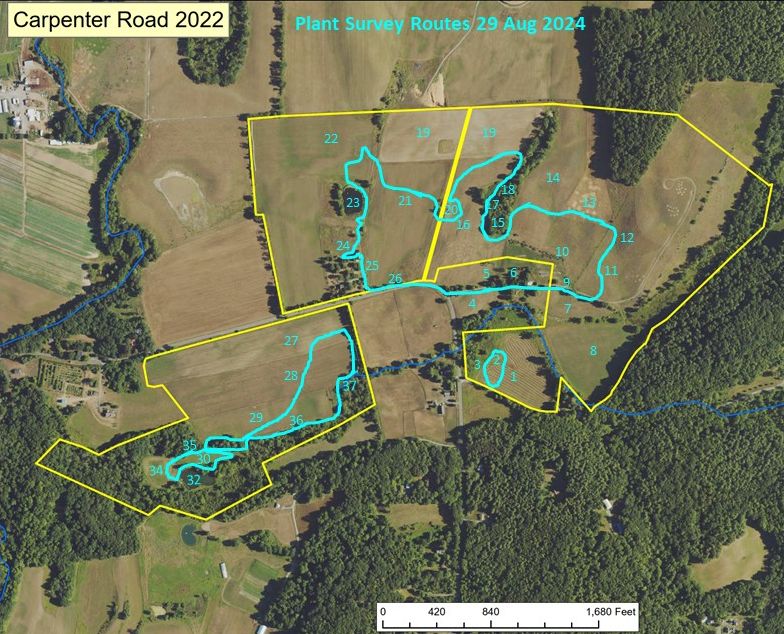

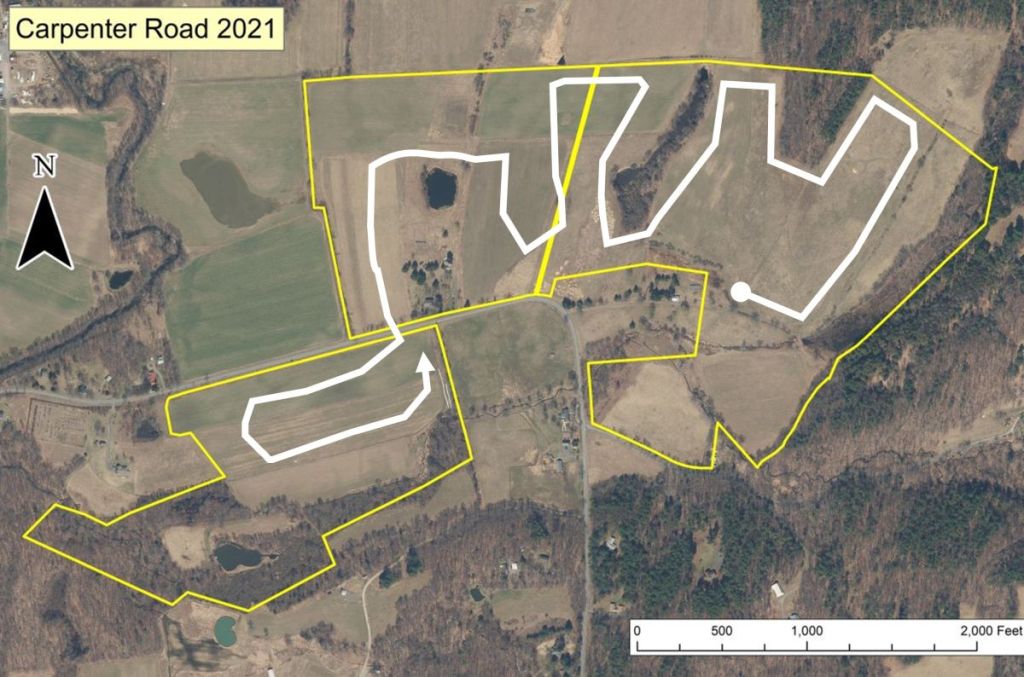

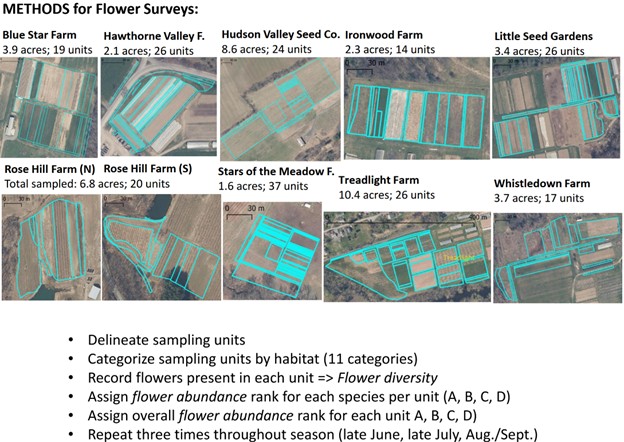

It is important to point out that we did not attempt to standardize the size of the study areas and number of survey units across farms. They were largely determined by practicality, the desire to include a variety of management regimes, the field conditions and our energy level during the first survey, and sometimes the preference/curiosity of the farmer. As a result, the study areas ranged from 1.6 acres to 10.4 acres in size and contained between 14 and 37 study units (Figure 2).

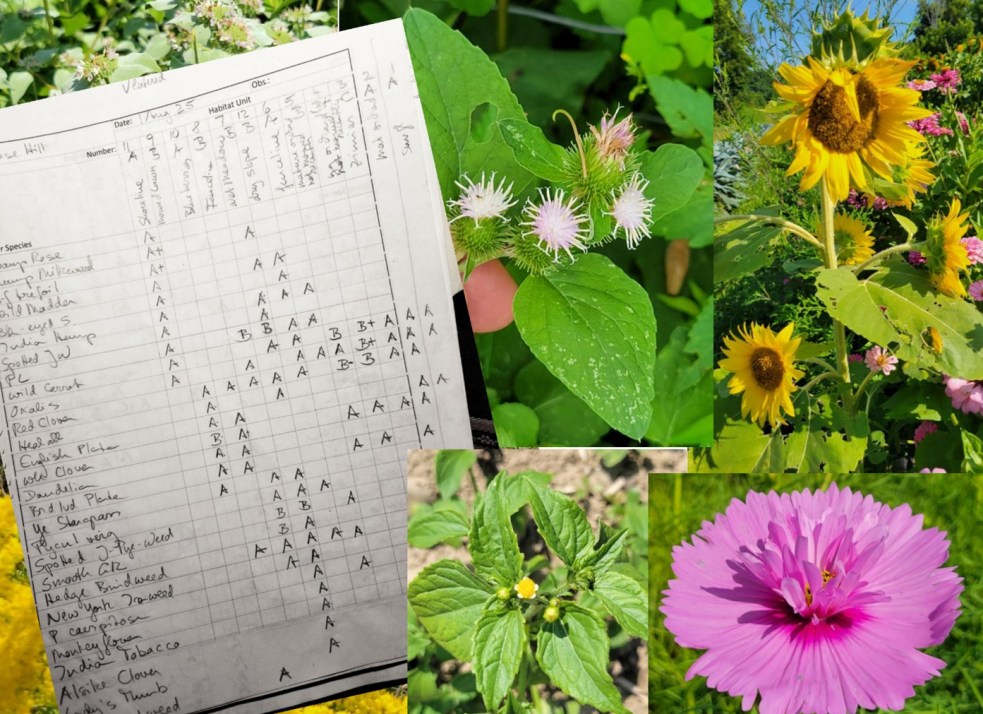

Within each survey unit, flower species present were noted, and they were given an abundance rating reflecting their abundance within the survey unit as a whole. We used four ranks, A-D to indicate increasing flower abundance. We also noted if there were no flowers in a unit. Each survey unit was also given an overall flower abundance rating considering all flowering species present. Back in the office, the various survey units were delineated on aerial images and the floral data were associated with the corresponding spatial data. This allowed the mapping of the abundance of individual flower species, overall flower diversity, overall flower abundances, and the diversity of such flower classes as wild-growing and cultivated.

Figure 2. A visual comparison of the study areas and survey units of the nine farms and a summary of the methodology for the flower surveys

Figure 3. Example of a field data sheet used in the flower surveys and some of the flowers encountered during these surveys (clock-wise from top left): Clustered Mountain-mint, a budock species, Common Sunflower, Garden Cosmos, a quickweed species, and a goldenrod species.

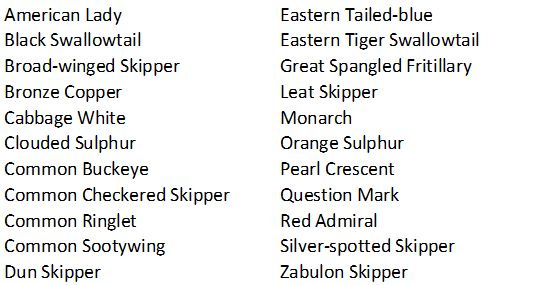

Flower Visitors. Conrad took his cue from the flowers that Claudia identified and tried to visit, if not all flower species, then at least the most common ones. For each flower species observed, an attempt was made to spend five minutes inspecting new flowers of the focal species. If the flowers were organized in a bed, then this meant walking down the bed, with eyes moving from flower to flower as the presence or absence of a flower visitor was determined. A stopwatch was used and only time spent inspecting new flowers was included in the timed observations; if Conrad was distracted or if a given flower was discontinuously distributed, timing stopped during the non-observational activity (e.g., taking photos) or during the walk to another flower of that species. Sometimes low flower availability meant that it was not practical to fill five minutes with flower observation; in such cases, the total period of actual observation was recorded. As alluded to earlier, a few relatively crude taxonomic categories were used to tally flower visitors in most cases. For bees, the tally categories were Honey Bee, Eastern Carpenter Bee, bumble bee and “other bee”. However, Eastern Carpenter Bees were relatively few, and so are excluded from some analyses. Effort was made to ID unusual bumble bees and “other bees” was in part the sum of several other, more specific bee tallies including those of Hylaeus (the tiny masked bees), Green Sweat Bees, and Ceratina (the smaller carpenter bee). These added data are summarized in some ancillary analysis, but only the four aforementioned categories of bees were used for the core analysis. Other, non-bee groups included butterflies, wasps, and hover flies. Butterflies were usually identified to species, and some additional ID attempts were made of other flower visitors but, again, these are not included in the core analysis.

Figure 4. The six main insect groups tallied during this work, together with the name of the farm where the photos happened to come from.

Once the raw observational data were collected, they were corrected in two ways. First, the total number of sightings was divided by the duration of the observations to get sightings per minute of observation. This was necessary because, as noted earlier, not all observations lasted for five minutes. Next, the rate of observation on a given flower and for a given flower visitor (say, bumble bees visiting Zinnia at Little Seed Gardens on June 19th) was divided by the average rate of observation for that insect taxon across all flowers observed at the farm on that date (i.e., all bumble bee observations on flowers at Little Seed Gardens on June 19th). This was done because our goal was to calculate an index of relative flower favorability, and we wanted to take into account the fact that the ‘background’ levels of flower visitors might vary for a variety of reasons (e.g. if the preceding couple of days had been particularly cool and rainy, but the observation day was warm and sunny, then bumble bees might be especially active and so any ‘raw’ rates of observations from that day would likely over-value actual relative favorability).

The relative favorability ratings were then used in several different ways: first, they were used to create a table of favored flowers for each insect taxon; second, they were used to look for general patterns (e.g., were native vs non-native or cultivated vs wild-growing flowers more likely to attract certain taxa of insects?); and, finally, they were paired with Claudia’s species-specific flower abundance data for each survey unit in order to spatially and temporally map the appeal of a farm’s survey units for a given insect group.

RESULTS: What we found?

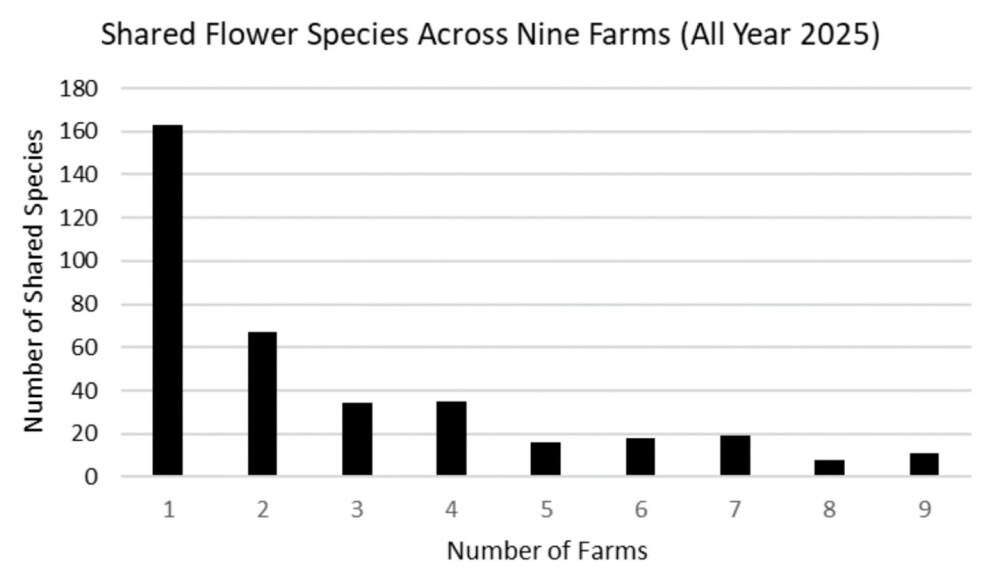

Flowers. We found a total of 371 species of plants in bloom across the nine farms (see here for the complete list). Of these, 162 were only found on a single farm (Figure 5). The farms ranged from harboring as few as three to as many as 37 unique blooming plants. Eleven species of flowers were found on all nine farms. These ubiquitous species were three native species: Daisy Fleabane, Horseweed, and Tall Goldenrod; and eight non-native species: Common Bedstraw, Common Ragweed, Common Yellow Wood-sorrel, Lady’s-thumb, Narrow-leaved Plantain, Red Clover, White Clover, and Wild Carrot (aka Queen Anne’s Lace). Farm-specific lists of plants observed in bloom are included in the individualized farm reports available from the links below.

Figure 5. Graph illustrating the number of unique flower species (i.e., those found only at a single farm) in our study, as well as the number of species shared by two or more farms.

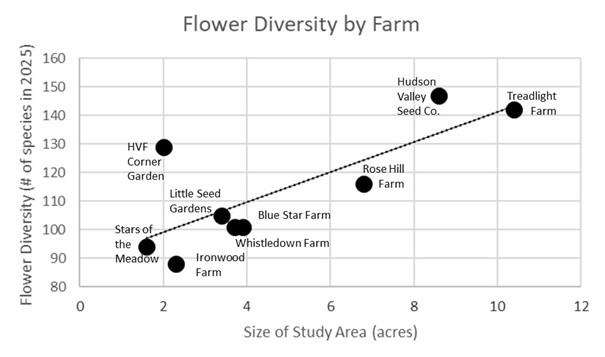

Not surprisingly, the size of the study area on each farm had a large influence on the total number of flower species tallied – in general, the larger the area we studied, the more different kinds of flowers we observed (Figure 6). It also didn’t come as a surprise that the larger cut flower farms (Hudson Valley Seed Co. and Treadlight) and the farm with intentionally installed and managed pollinator habitat (Hawthorne Valley Farm) had the highest flower diversity.

Figure 6. Flower diversity in relationship to the size of the study area at each farm

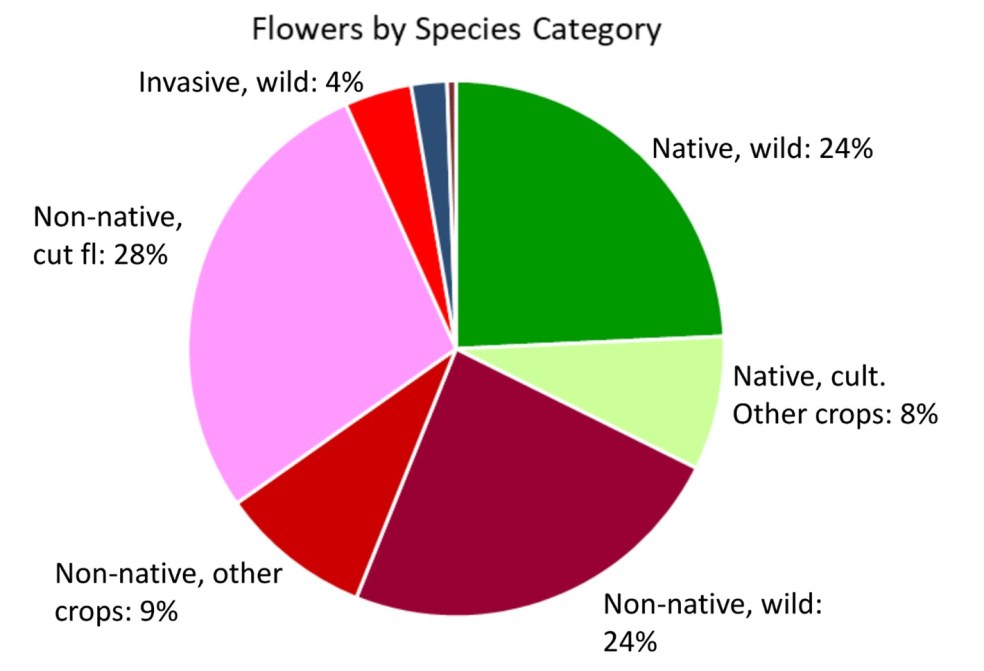

The following pie chart (Figure 7) illustrates the various categories of plant species observed in bloom at the nine farms in 2025.

Figure 7. Plant species observed in bloom at the nine study farms by categories

Approximately 32% of these blooming species were native and about 52% were wild-growing.

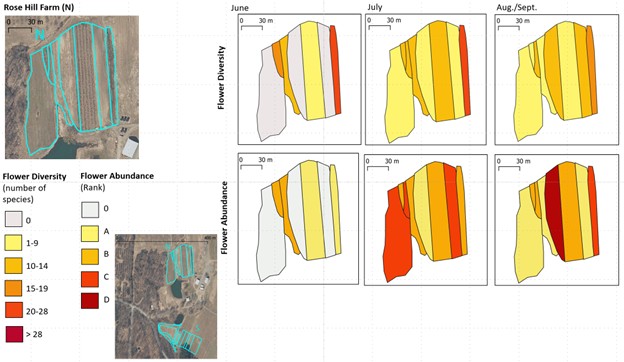

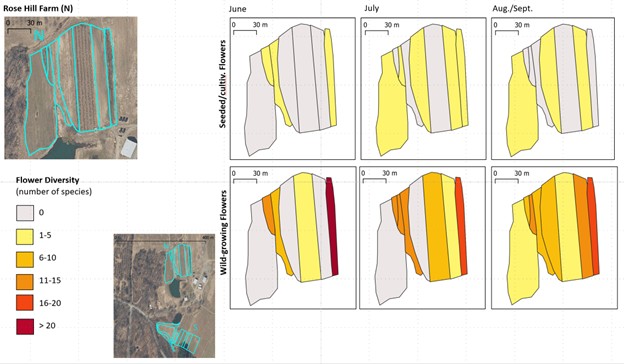

For each farm, we created maps of flower diversity and abundance in each survey unit across the three sampling months (see example in Figure 8).

Figure 8. Example of a map comparing flower diversity (upper row) and flower abundance (lower row) in the survey units of a farm. Maps for each farm are included in the farm reports linked to below.

In general, we learned that both flower diversity and abundance changed quite a bit in the survey units of each farm across the growing season. However, flower diversity and abundance were often not tightly correlated. Some survey units had a high abundance of the flowers of a few species. Others had a lot of species with few flowers each. Many were in-between.

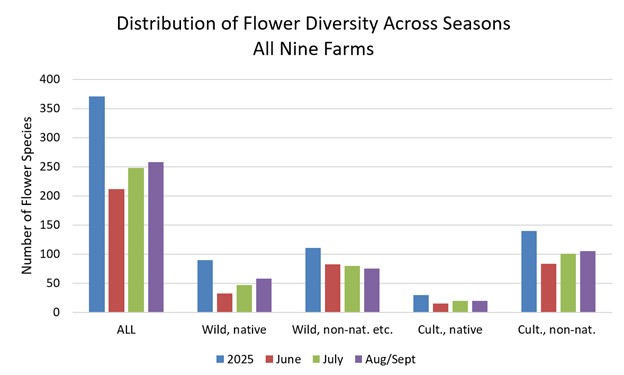

The following graph (Figure 9) illustrates the distribution of flower species at the nine farms in four categories (wild-growing native species, wild-growing non-native species and taxa of uncertain native status, cultivated native species, and cultivated non-native species) across the survey periods.

Figure 9. Distribution of flower diversity by species categories across the survey periods. Wild-growing plants of unknown native status were included in the “wild, non-nat. etc.” category for simplicity. Farm-specific versions of this graph are presented in the individual farm reports.

Wild-growing native flowers and cultivated non-native flowers increased in diversity across the season, while the diversity of wild-growing non-native flowers was overall somewhat higher early in the season. There was some variation in these seasonal patterns between the farms (see individual farm reports linked below), but seven of the nine farms had a clear trend for increasing diversity of wild-growing, native species later in the season.

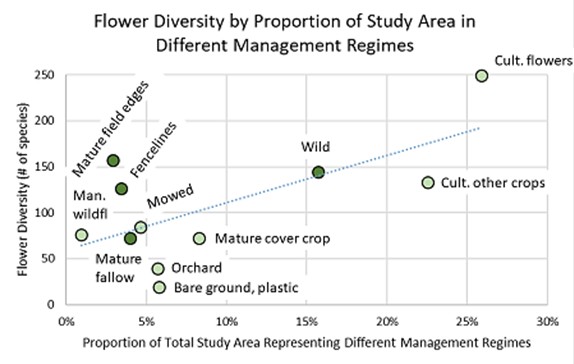

The next graph (Figure 10) shows the relationship between flower diversity (all species categories, across season) and management regime, based on the relative size of the total survey area (the sum of all survey units) in each management category.

Figure 10. Flower diversity in different management regimes relative to their portion of the total study area. dark green circles indicate unmanaged or lightly-managed habitats, the light green circles intensively-managed ones.

Of the unmanaged or lightly-managed habitats, mature field edges and fencelines had a disproportionately high diversity of flowers compared to the sample area they occupied, while wild areas and mature fallow each had a flower diversity that was expected for its proportion of the study area (their dots fell almost exactly on the trendline). This hints at the potential importance of narrow edge habitats. Not surprisingly, the beds of cultivated flowers were more diverse than expected relative to their size.

For each farm, we also created maps of the diversity of wild-growing vs. seeded/cultivated flowers in each survey unit across the three sampling months (for example, Figure 11).

Figure 11. Example of a map comparing the diversity of seeded/cultivated flowers (upper row) with that of wild-growing flowers (lower row) in the survey units of a farm. Farm-specific versions of this map are included in the individual farm reports linked to below.

These maps remind us of the fact that, even on farms with relatively high diversity of cultivated flowers, most survey units had significantly more wild-growing flowers. That was true not only for the fencelines and field margins, but also for more intensively-managed habitats.

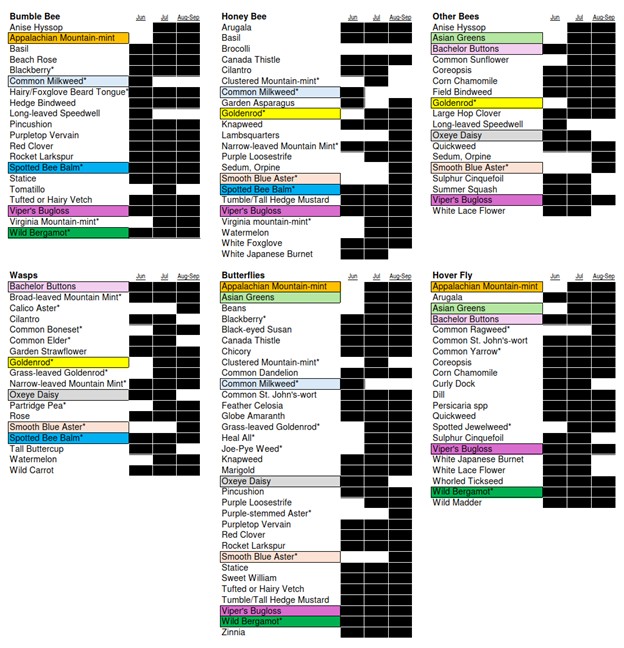

Species-level Flower Favorability. Table 1 shows the flower favorability ratings by insect taxon. As described in the “What did we do?” section, these were calculated by counting the bees (and other insects) seen during five minutes of continuously scanning new flowers of a focal plant species. For the given flower, all observation rates on all farms and during all outings were averaged.

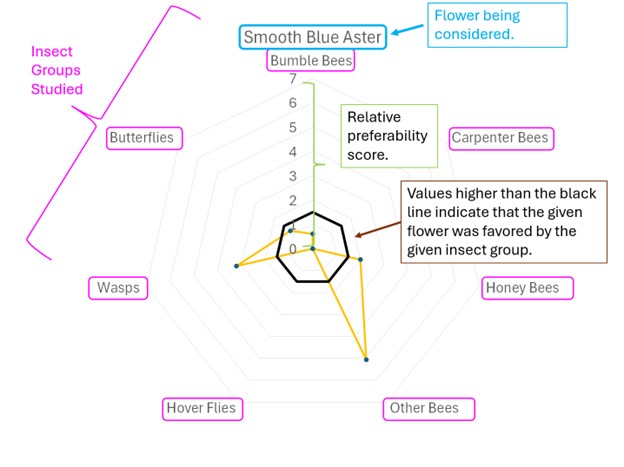

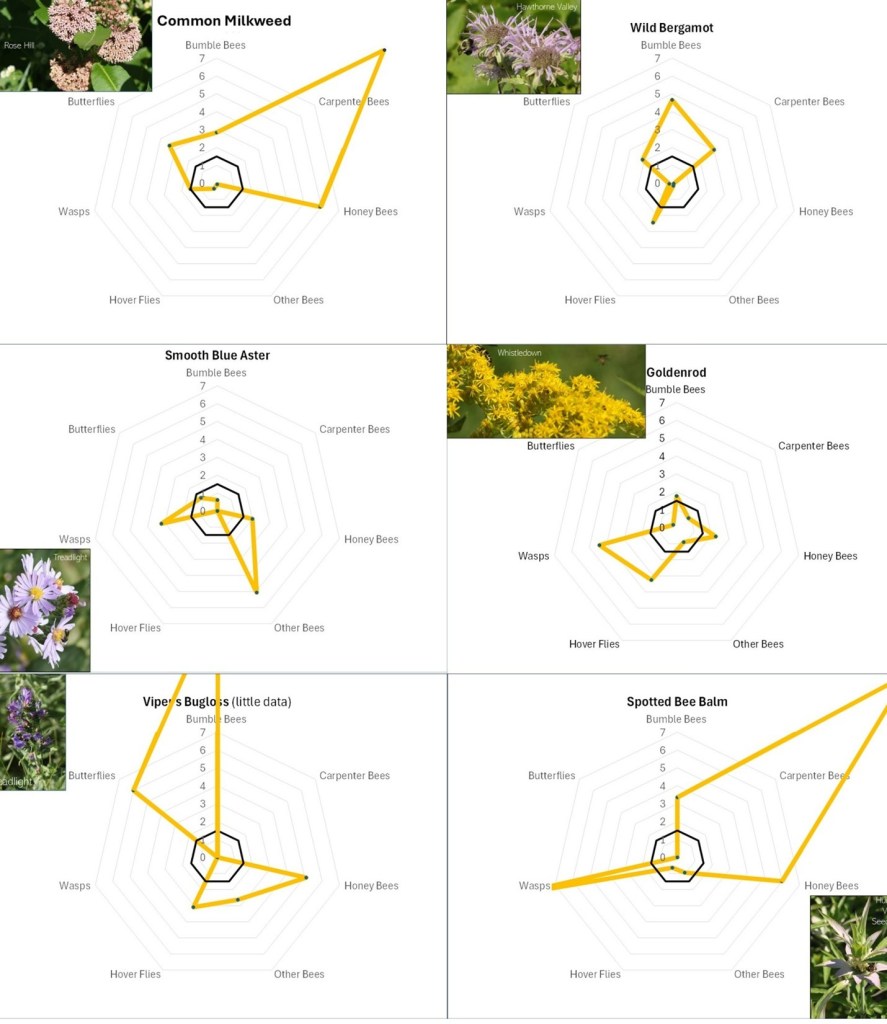

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Table 1 is how distinct the lists are for the different taxa. Even amongst the different groups of bees, the repetition of favored flowers across the lists is modest. A few flowers, highlighted in color, were favored by three or more insect categories. These included: Appalachian Mountain Mint, Asian Greens, Bachelor Buttons, Common Milkweed, goldenrod, Ox-Eye Daisy, Smooth Blue Aster, Spotted Bee Balm, Viper’s Bugloss and Wild Bergamot. (Note that “goldenrod” refers to several species including Tall, Wrinkle-leaved and Smooth Goldenrods). One way of visualizing the roles of different flowers in supporting a range of flower visitors is by the use of radar graphs like those shown below (Figures 12 and 13 A-D).

Table 1. The flowers most favored by our six insect groups, based on observational data from all farms and all outings. Lists are alphabetical and only include those flowers with notably higher than average visitation rates by the given insect groups. Plant species native to the Hudson Valley are marked with an asterisk. Colored boxes highlight those species found on three or more lists. Black blocking indicates flowering times observed during the season. CLICK ON IMAGE FOR ENLARGEMENT.

Figure 12. Explanation of a radar diagram illustrating insect preferences for a particular flower. The names of the various insect groups studied is displayed around the circumference. The distance from the center point to the edge reflects the strength to which the respective insect group favored the particular flower by each insect group. The dark black circle indicates what would be a slightly above average favorability for that particular insect group across all flowers. Finally, the orange zig-zag indicates the data for the particular flower. In this case, Smooth Blue Aster was highly favored by ‘other bees’, and somewhat favored by wasps and Honey Bees.

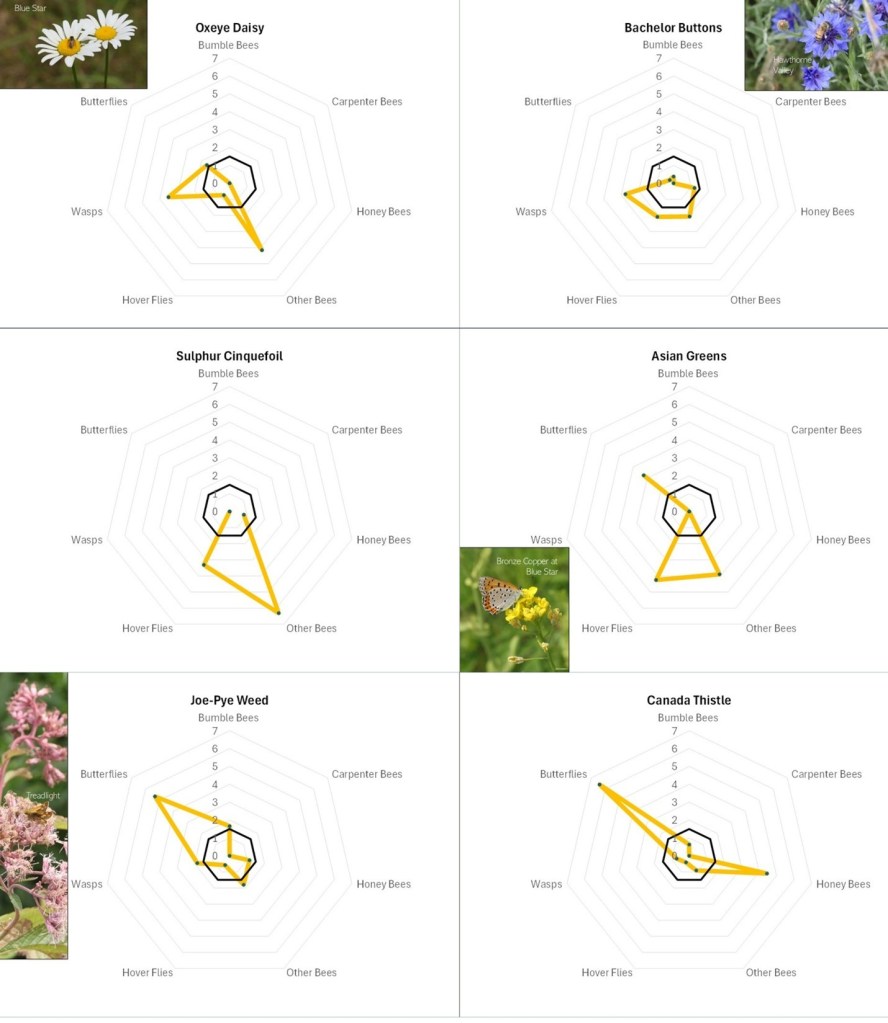

Flowers with different offerings display different shapes on the radar graph, and scanning such images can quickly illustrate differences in the preferences associated with each flower. For example, in looking at Figure 13A, Common Milkweed’s wide-ranging appeal to larger insects (i.e., butterflies, bumble bees, carpenter bees and Honey Bees) is easily noted, as is the appeal of goldenrod (Fig. 13A), Sulphur Cinquefoil (Fig. 13B) and Bachelor’s Button (Fig. 13B) to the shorter-tongued creatures.

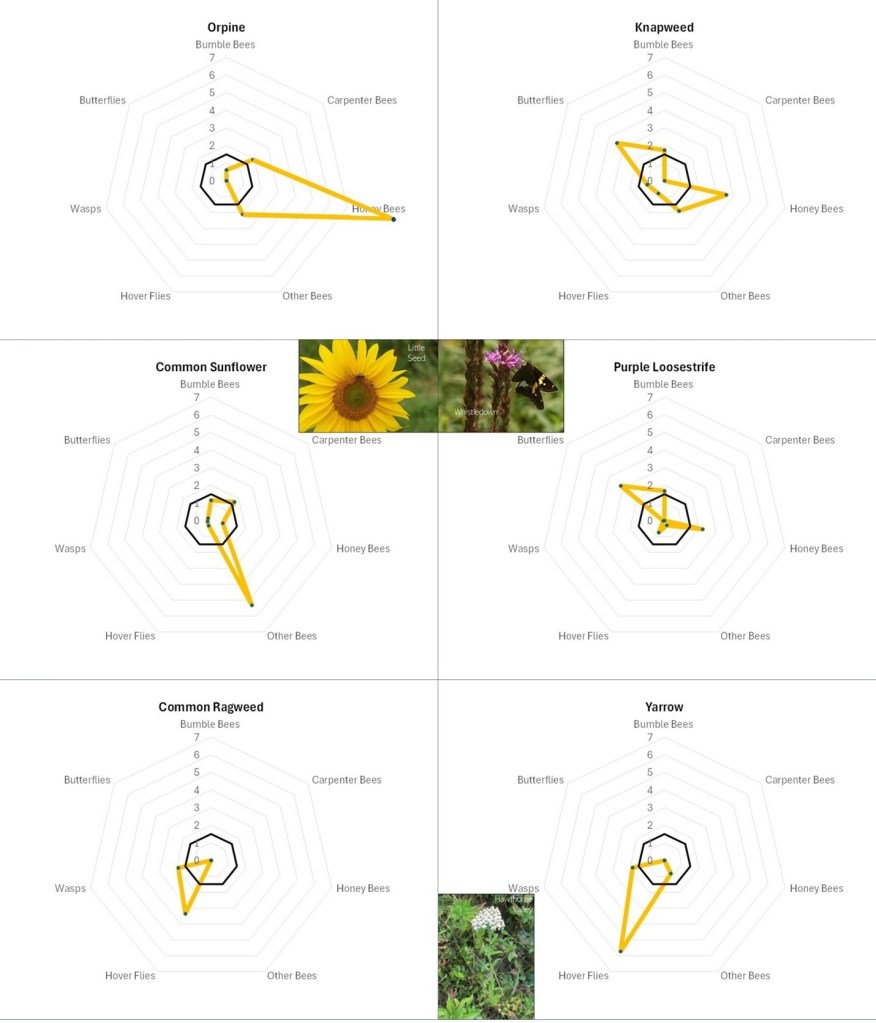

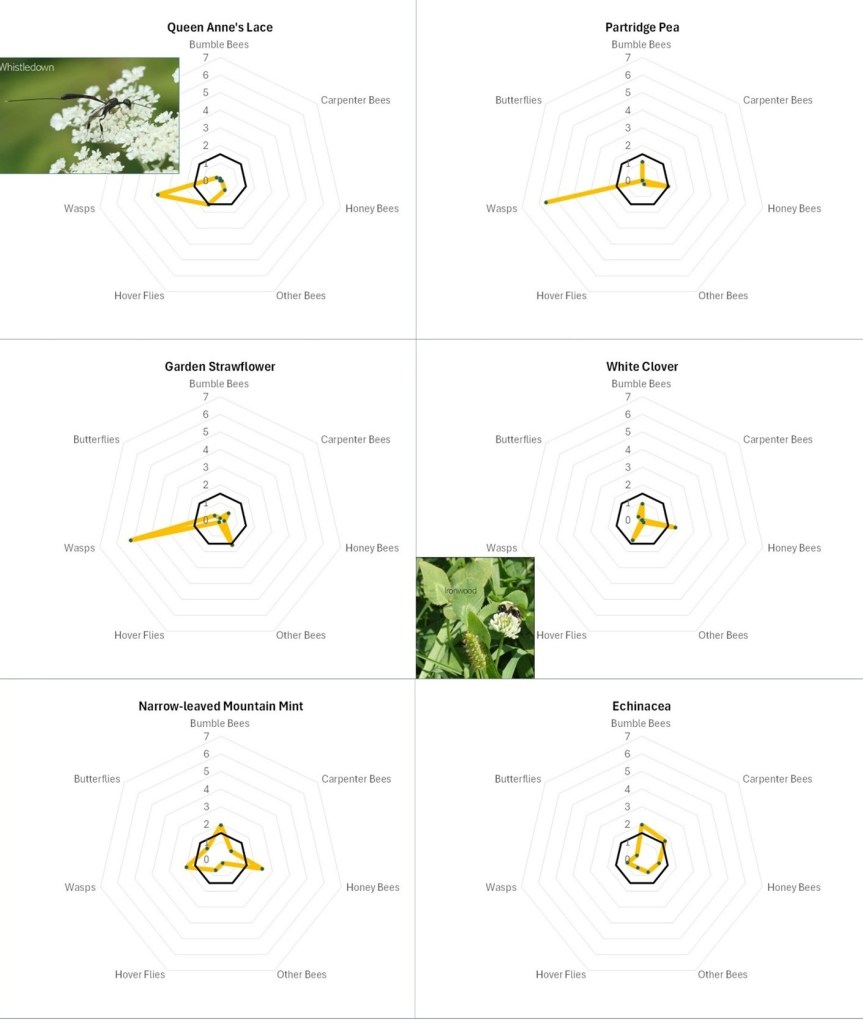

Even at this very general level, it is clear that this is, as mentioned, a case of “different strokes for different folks”. The variation in favored flowers amongst the insect groups relates in part to the mouth parts, color preferences, and nutrient requirements of the particular insects and, conversely, the flower depth, color, and pollen and nectar offering of the flower. For example, wasps do not usually have long tongues and so seem to prefer shallower flowers, such the goldenrods (Fig. 13A), the mountain mints (Fig. 13D), and Queen Anne’s Lace/Wild Carrot (Fig. 13D). Bumble Bees can usually tap deeper flowers, and so favor the likes of Wild Bergamot (Fig. 13A), Common Milkweed (Fig. 13A), and Viper’s Bugloss (Fig. 13A). However, long-tongued species can feed on shallow flowers, and shallow-tongued species can ‘short-circuit’ long flowers by biting through the tubes leading to the nectar reservoirs.

Figure 13A. Radar diagrams illustrating the favorability scores of various observed flowers. See Figure 12 for explanation.

Figure 13B. Radar diagrams illustrating the favorability scores of various observed flowers. See Figure 12 for explanation.

Figure 13C. Radar diagrams illustrating the favorability scores of various observed flowers. See Figure 12 for explanation.

Figure 13D. Radar diagrams illustrating the favorability scores of various observed flowers. See Figure 12 for explanation.

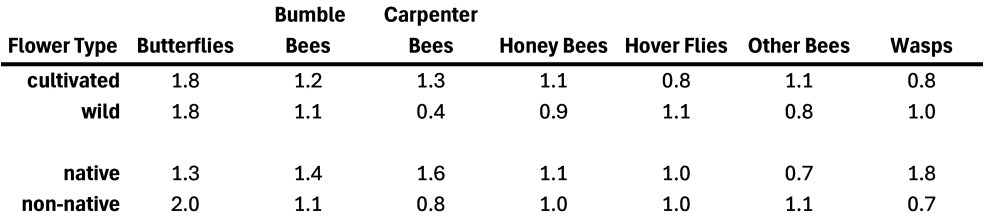

A Couple of Key Questions. The above results pertain to specific flower species, but, as mentioned earlier, we were especially curious to know if any generalities could be made regarding the value to flower visitors of native vs. non-native flowers and of cultivated (seeded or planted) vs wild-growing flowers. To answer these questions, we compared the visitation rates of our focal insect groups to cultivated vs wild-growing and to native vs. non-native flowers (see Table 2).

Table 2. The average per-minute visitation rates of the different insect groups of seeded vs wild, and native vs non-native flowers.

In general, this seems to be another example of the ‘different strokes for different folks’ pattern. For example, some insect groups seemed to favor wild-growing plants and others favored cultivated ones. There may be a hint here that short-tongued creatures (e.g., wasps and hover flies) favor the wild flowers, perhaps because people are less likely to cultivate the small, shallow flowers these species can favor, and so such flowers are more common as ‘weeds’ (such as Queen Anne’s Lace/Wild Carrot or Daisy Fleabane). Butterflies and bumble bees seem noncommittal, while Carpenter Bees, Honey Bees and Other Bees seemed to favor the cultivated flowers. The Eastern Carpenter Bee’s apparently dramatic taste for cultivated flowers came about in large part because they favored a couple of the cultivated mountain mints, a couple of bee balms plus Nasturtiums and Celosia. However, Common Milkweed, a wild-growing species, was also frequented. Native plants were favored by those same Carpenter Bees (because they used several native but cultivated species), but also by bumble bees and wasps, while butterflies and other bees seemed to favor the non-native flowers. Note in relation to butterflies that we are ONLY talking about nectaring by adult butterflies, it’s likely that caterpillars are more discerning and that native butterfly species would favor native host plants as larval food.

Based on the limited evidence from our work, we would say that both cultivated and wild-growing, and both native and non-native species have roles to play in supporting our flower visitors.

We’ll return to the management implications of these results after describing the content of the individualized farm reports.

MAPPING: Individualized Farm Reports

Overview. While the above general information is useful, farm-specific maps showing the occurrence of plants, the management regime, and apparent favorability of survey units for flower-visitors can provide an intuitive and useful outline of each farm’s flower resources. Thus, many of the data generally described above were mapped for each farm. These maps are included in the farm reports available as links below. In the spirit of discussion that motivates this group, those individual farm results are being made available to all. Nobody is doing things ‘better’ or ‘worse’ than anybody else, but each farm is different and so can provide new lessons.

The links immediately below will take you to .pdfs of each farm’s report:

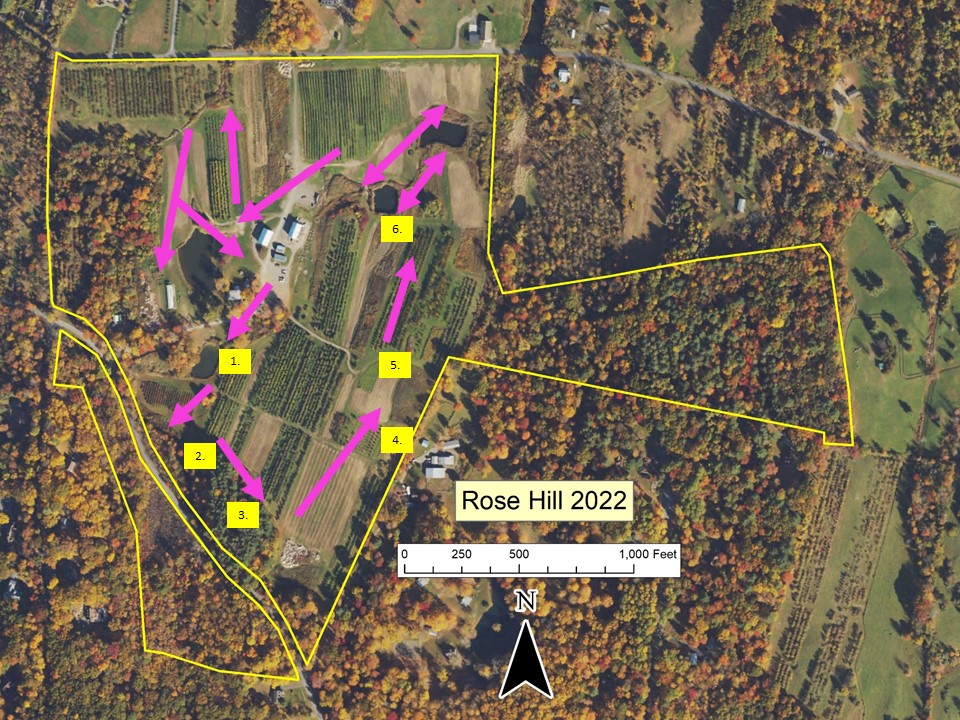

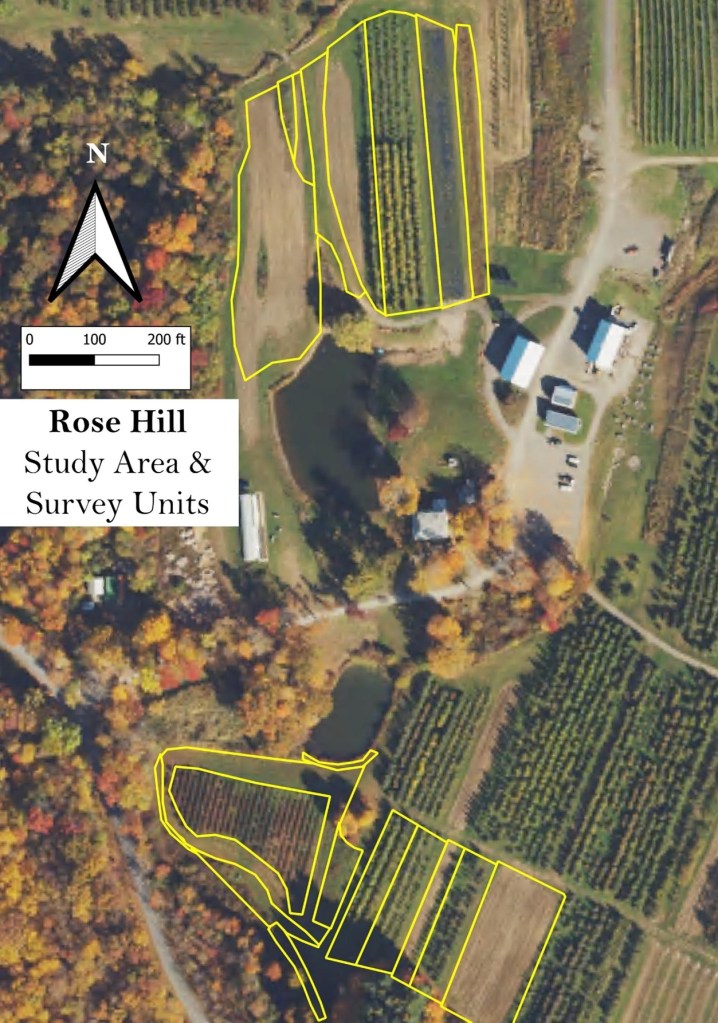

Following, we illustrate what you can expect in the individual farm reports with examples from Rose Hill Farm.

Survey units and Management Regimes. The first step was to outline the area that would be studied on each farm, to delineate survey units, and to determine their management regimes. As noted earlier, due to practicality, in all cases the potential foraging range of a bee substantially exceeded the study area we surveyed, and they may well be collecting resources farther afield. Work we did on several Hudson Valley orchards suggested that land use within at least 1600 ft of the orchard affected the bees found during spring bloom, indicating a relatively wide ‘sphere of influence’.

Rose Hill happened to be unique in that we decided to study two completely separate sections of the farm. Figure 14 shows the survey units we delineated in the two study sections in July. On some farms, the shape or the number of survey units varied somewhat across outings. This could occur if, for example, a field with several beds of different crops early in the summer (which would be divided into several survey units) were to be plowed up and made into one uniform field with a cover crop (which would then be delineated as a single survey unit) later in the year.

Figure 14. Study area and survey units delineated at Rose Hill during July.

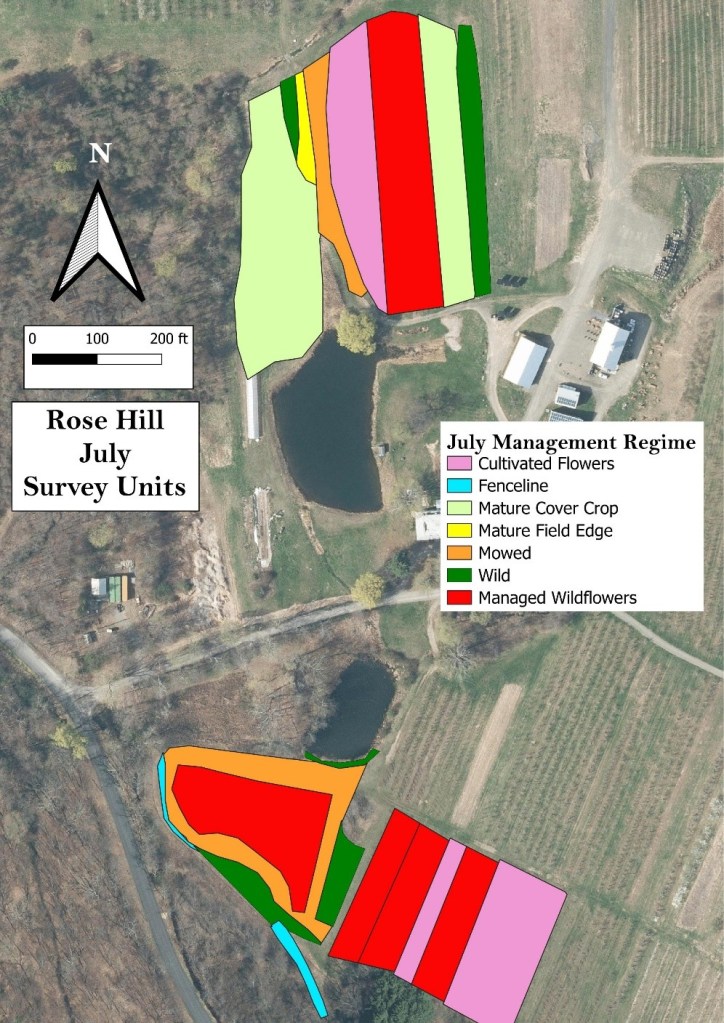

The survey units usually represented several different management regimes. For example, at Rose Hill (Fig. 15), the survey units represented fruit crop production (orchard and blueberries), mowed lawn, cultivated flowers, fenceline, mature cover crop, mature field edge, and wilder areas. On each farm, an effort was made to include examples of both more and less intensively managed habitats, because of our goal to compare the value of wild-growing and cultivated flowers.

Figure 15. Generalized management regimes in the Rose Hill survey units during July.

Botanical Mapping. As described above, within each of the survey units, the flowering species (and only those species actually in bloom during the given outing) were recorded three times during the 2025 season, and their individual and total flower abundances ranked. While it would be theoretically possible to do, we have not mapped the occurrences of individual flower species. Instead, we mapped summary statistics such as flower abundance and flower diversity, and the ratio of wild-growing vs. cultivated flowers (see example maps above).

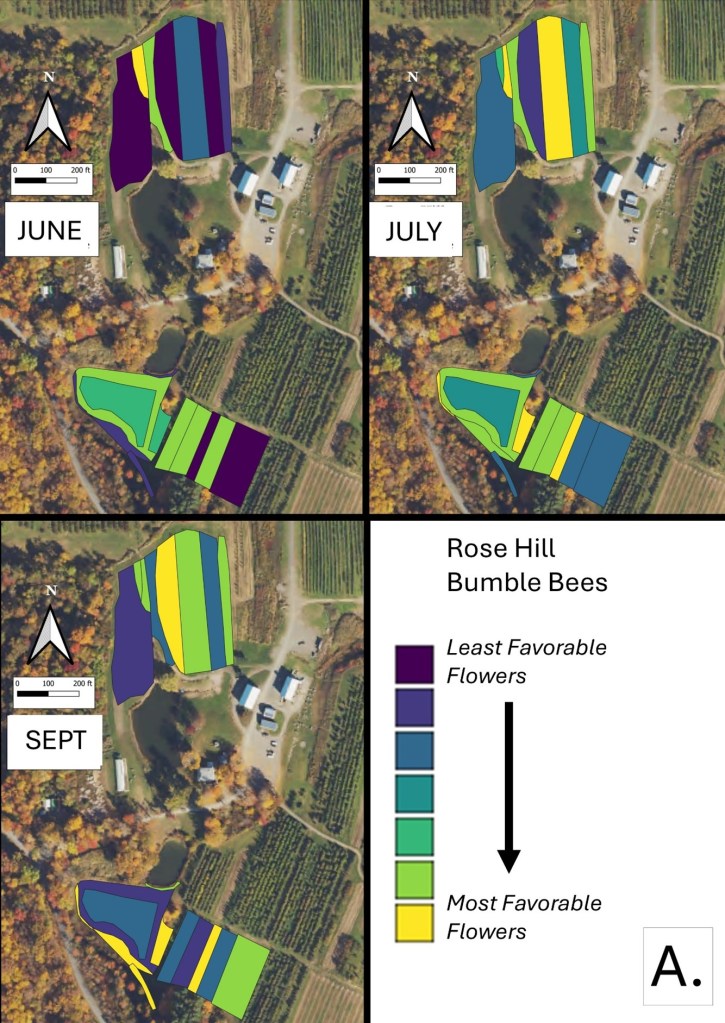

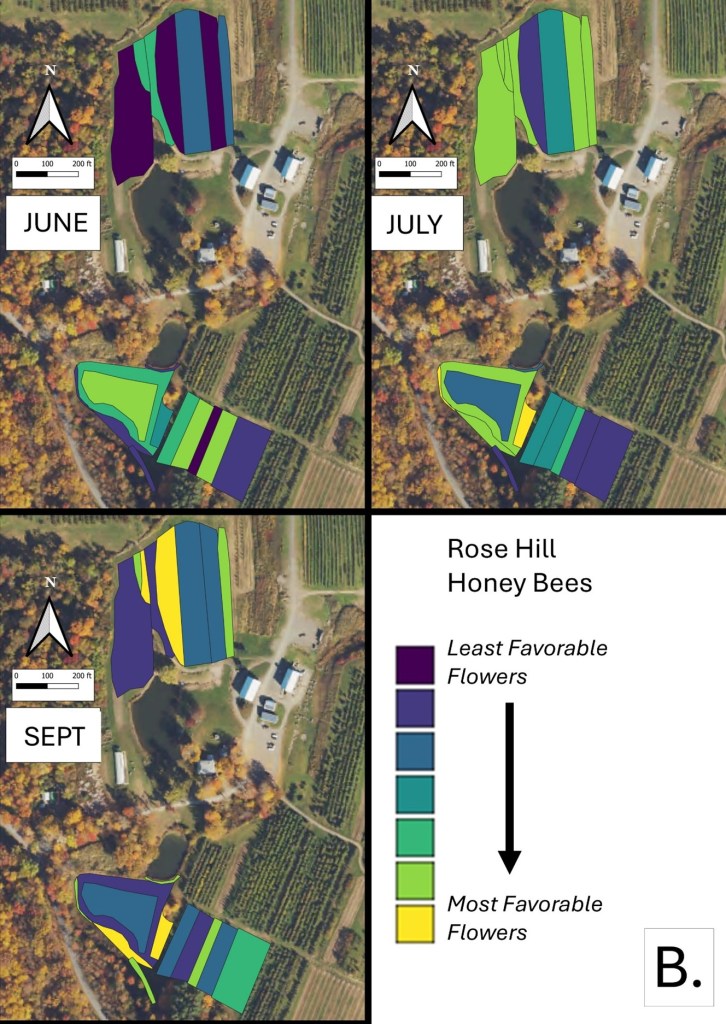

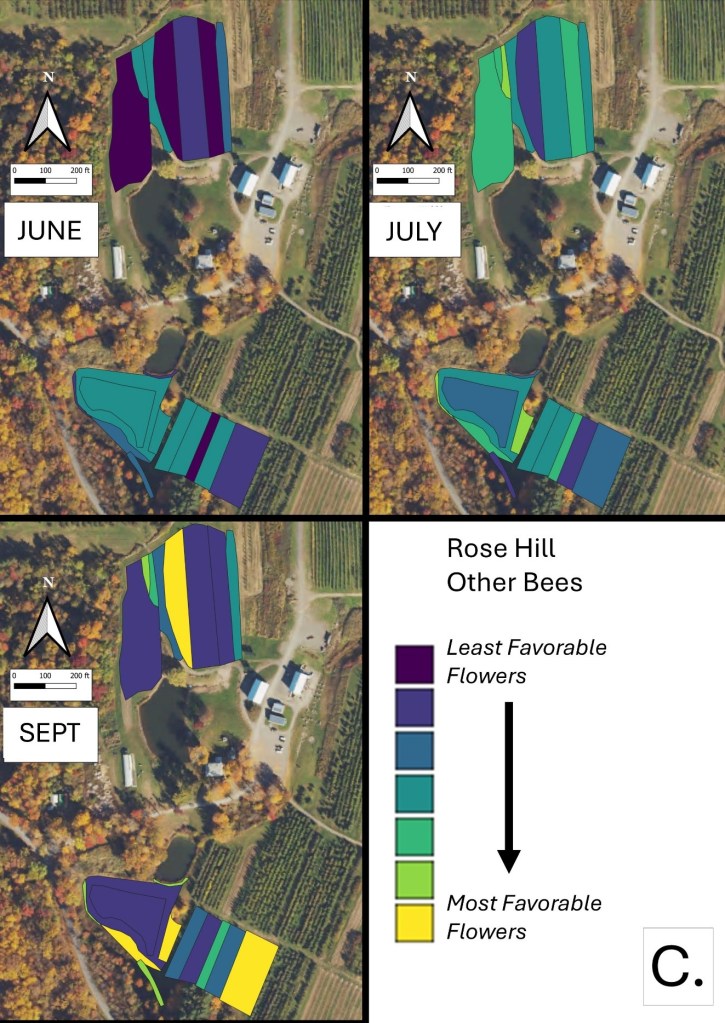

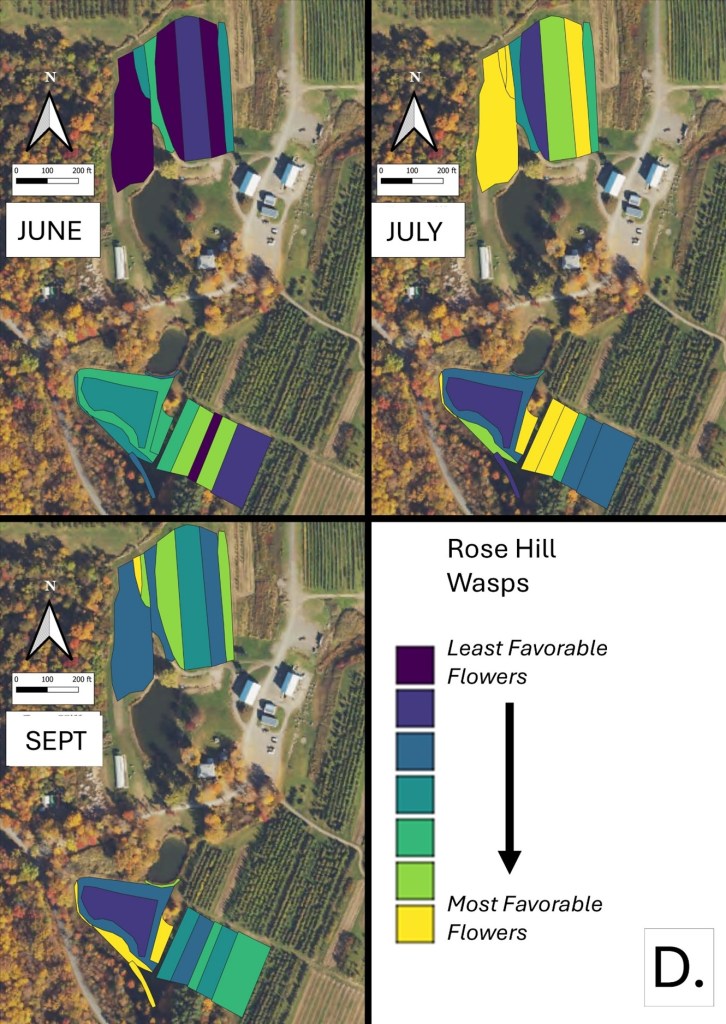

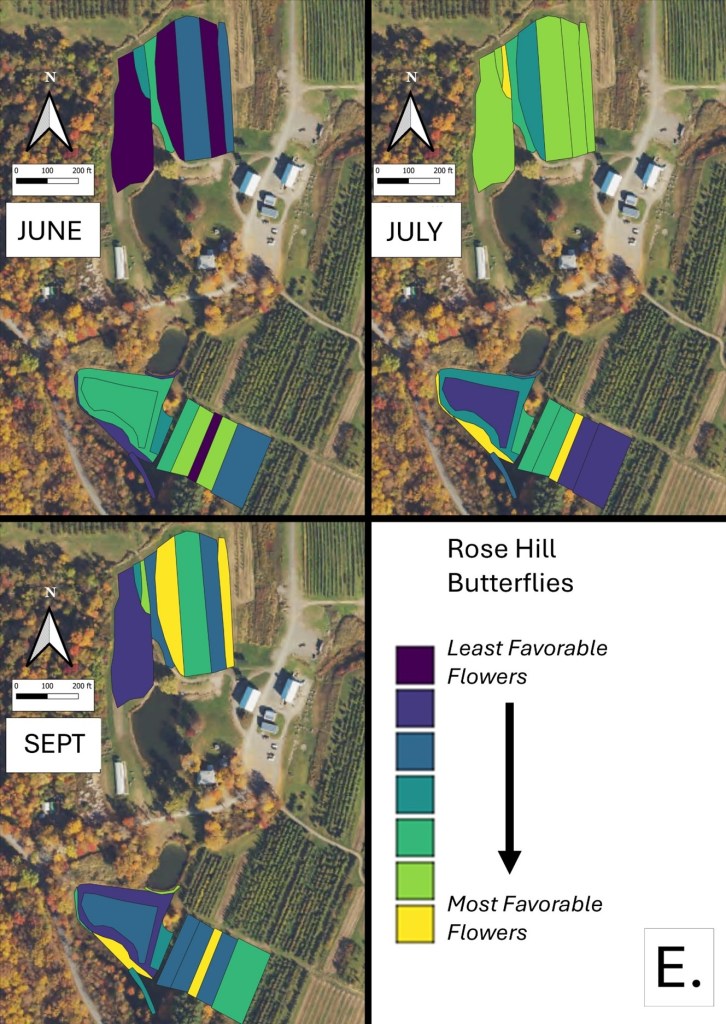

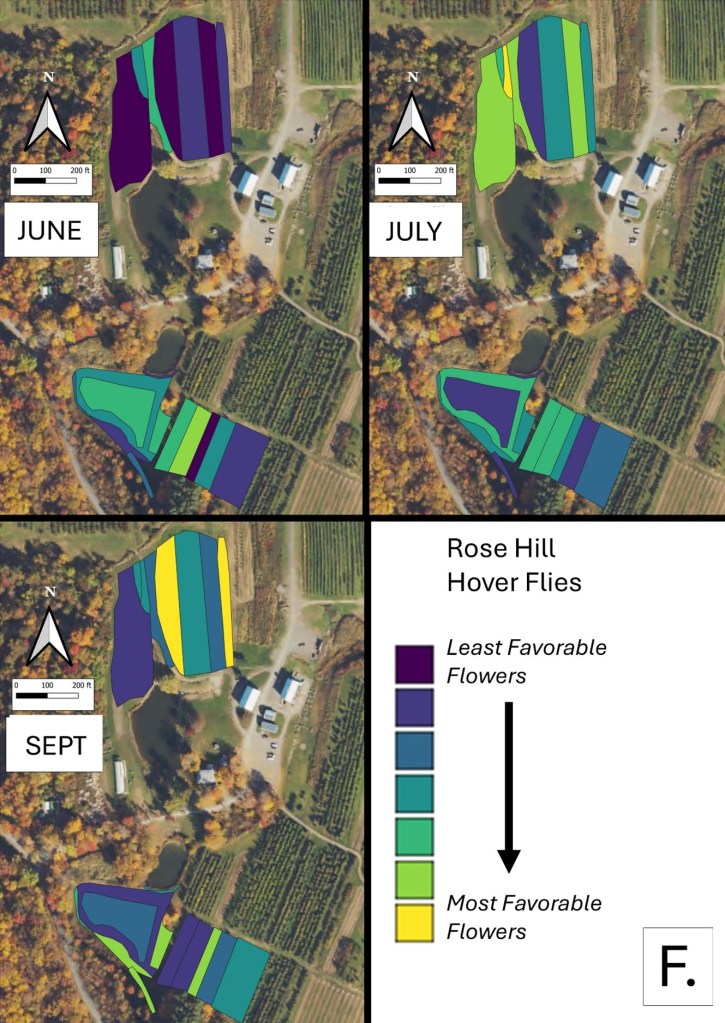

Mapping Flower Favorability. Finally, we took the flower information and combined that with insect-taxon specific flower-favorability ratings to create predicted favorability ratings for each survey unit and insect taxon during each of the three surveys. (Figures 16 A-F). Within insect groups, it is valid to compare colors across outings and farms. In other words, were one looking at bumble bees, a yellow bed at Rose Hill in July is indeed predicted to be more favored than a bed that is blue at Whistle Down in June. However, in absolute terms, colors are not equivalent across insect groups, even within the same farm.

Remember, these maps are NOT maps of actual insect densities. Such maps would be interesting but were beyond our means this past summer. Instead, these maps show the predicted favorability of each survey unit for a given flower visitor based on, as already noted, the unit’s botanical composition and the observed flower visitation rates gathered across all farms and survey months. Nonetheless, we think they provide a relevant depiction of the flower resources on offer.

Figure 16A. Flower favorability for bumble bees in the different survey units and months at Rose Hill. Generally, darker signifies less favored flowers, and lighter colors mean more favored.

Figure 16B. Flower favorability for Honey Bees in the different survey units and months at Rose Hill. Generally, darker signifies less favored flowers, and lighter colors mean more favored.

Figure 16C. Flower favorability for ‘other bees’ in the different survey units and months at Rose Hill. Generally, darker signifies less favored flowers, and lighter colors mean more favored.

Figure 16D. Flower favorability for wasps in the different survey units and months at Rose Hill. Generally, darker signifies less favored flowers, and lighter colors mean more favored.

Figure 16E. Flower favorability for butterflies in the different survey units and months at Rose Hill. Generally, darker signifies less favored flowers, and lighter colors mean more favored.

Figure 16F. Flower favorability for hover flies in the different survey units and months at Rose Hill. Generally, darker signifies less favored flowers, and lighter colors mean more favored.

SO WHAT?: How to use these data

Table 1 (the table of favored flowers by insect taxon) can be useful because it provides broad-brush information on what flowers might support which flower visitors. This information is hardly unique (see for example the work of Xerces), but it is specific to the insects and plants of our region. If, for example, you wanted to create flower beds that offered resources to an array of insects, you could plant (or allow to bloom) a mix of flowers from across the lists for each taxon. Alternatively, if you wanted to focus on attracting/supporting one particular insect group, then you could plant heavily from that taxon’s flower list. Furthermore, you could somewhat refine what seasons you wanted to emphasize – if the maps suggested low bumble bee flower resources in June, then you could look for June-flowering, bumble-bee favored flowers. Do note that only flowers actually observed at our study farms during the summer 2025 were considered for inclusion on this list (see here for the complete list of all flower species observed during this study); there are surely other flower species, not seen during our study, that can support these insects.

The potential use for the favorability maps will also depend on your goals.

In glancing over the maps (Figures 16 A-F), first train your eyes – dark blue means low predicted favorability while bright yellow means higher favorability. So, if you scroll through the maps below, which insect groups seem to be most/least favored by the flowers at Rose Hill? In other words, which maps are lightest and darkest overall? My eye suggests that bumble bees are relatively favored, while hover flies, for example, are not. Whether that observation prompts management considerations depends, in part, on the importance attached to the aphid-controlling habits of many hover fly larvae. Were one interested in augmenting hover fly resources, one might consider planting more of the flowers listed in the hover fly column of Table 1. Do you see anything surprising? For example, you may well have correctly predicted that your bed of cultivated flowers would be attractive to Honey Bees and bumble bees, but did you realize that, for example, ‘weeds’ in your crops were supporting aphid-eating hover flies or that the taller vegetation along your fence was favored by wasps? If either of those are desirable, then how might those resources be expanded?

The next thing one can do is inspect the three monthly maps on each insect group’s page and ask, ‘how good does across-the-season flower favorability seem to be?’ While some insects do fly for only a relatively short period of time and so only need flower resources for that limited period, many others fly throughout the season and need good resources across that period for their populations to flourish. Look, for example, at the ‘other bees’ maps in Figure 16C. Note that favored flower resources for ‘other bees’ seem to be relatively sparse in June and July, although the situation looks better come late summer. Were one interested in promoting populations of ‘other bees’, then one might again refer to Table 1, and now search for early flowering species that are favored by ‘other bees’. Indeed, broadly speaking the availability of favored flowers in June looks to be low for most insect groups at our example farm (Rose Hill; Figures 16 A-F), and this observation might encourage the planting of a range of early-flowering species. (Realize that there is more to life than June-September, but we did not collect data on it. Expanding our surveys to include earlier in spring might be one important future undertaking.)

Finally, one can scan the maps and ask if there are any survey units which are consistently low in their favorable flower offering and, at the same time, are not integral to crop production. One potential example at Rose Hill was the westernmost unit of the northern study area. It was in ‘mature cover crop’ in mid July and, other than supporting a relatively high density of wasp-favorable flowers during that month, it seemed to provide relatively few floral resources. Of course, it may well be that that field is in rotation for some future use and not really available for tweaking, but, if not, then it might be a space where flower seeding could increase its contribution to supporting flower visitors.

We realize that there are numerous other considerations that come into play when planning flower management (e.g., reducing potential tick contact or Groundhog habitat, or increasing the ease of farm operations). These maps are only a resource that, if so desired, can be one ingredient contributing to your overall management decisions. More specific thoughts are provided with each farm report.

MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS: Questions raised and potential actions.

In considering the above flower favorability maps, we have walked you through some examples of specific management considerations. The linked farm reports include additional thoughts specific to each farm. However, in preparing those reports and considering those results, certain general management considerations and questions came to the fore.

One key consideration is that, as mentioned earlier, our study areas were generally much smaller than the home ranges of any of these insects. That meant that what we were observing in our survey units reflected not only the conditions in those units, but also the conditions – flower abundances, nesting resources, pesticide applications etc. – in a much larger area. Management for on-farm flower visitors is a bit like life: you do the best you can with what you’ve got, but you also realize that ‘outside forces’ will also play a substantial role. While we cannot hope to identify and quantify all the ‘outside forces’ affecting on-farm flower visitors, it may be worth considering, and to some extent exploring, the availability of shoulder season flowers outside and inside the study area, soil texture in relationship to ground-nesting bees and wasps, and additional flower resources during the main survey period but outside the survey area. We did not, but we could, try to document the role of, for example, forest or wetland areas in providing flower resources and potentially nesting resources. Other factors relating to, for example, climate change and off-farm land management (e.g., urbanization, use of pesticides) might help put on-farm results in context, but may not be as interesting because they are largely outside a given farmer’s management purview.

There is however at least one aspect of the larger landscape management that might be worth exploring further and that is the potential for synergies between collaborating, adjacent farms. Out of the nine farms we studied last summer, at least three were adjacent to other ‘ecological’ farming operations. In one case, this was a focal veggie farm next to a flower farm and, in two cases, it was focal flower farms adjacent to another operations. What benefits and costs derive from such juxtaposition? In terms of encouraging a broader consideration of what is meant by an ‘agrarian landscape’, might it be useful to try to document these interactions in greater depth?

More broadly this work posed at least a quartet of general agroecological questions:

To what degree do ample flower resources augment pollination services by increasing pollinator populations and to what degree do they reduce crop pollination by distracting pollinators from that task? Others have studied this somewhat in relationship to fruit pollination where a sudden, short burst of flowers calls for an ‘all hands on deck’ response from pollinators. How does this same logic apply to flower beds amongst ‘pollinator hungry’ crops? Trying to provide a detailed dynamic heat map of flower visitor abundances across the season at even a single farm might help illustrate the ebbs and flows of pollinators and other insects, which, in turn, might help us better incorporate these movements into the pollination of crops. Such a consideration is less directly relevant to parasitoid wasps and hover flies, where the main agroecological service is not directly provided by the flower-visiting adult, but rather by the feeding of the larvae (either as parasitoids or aphid-eating maggots).

And, related to that and the earlier considerations, what are the limiting factors affecting flower-visitor populations? Think of a football team and what affects its chance of winning – if the quarterback can’t throw worth a darn, then that may be the most immediate limit on the team’s chance of success, but once you get an all-star quarterback, then the shoddy defensive team might be the main limit, get them up to snuff and your running back’s slowness might be the sticking point… Likewise, if flower visitors are receiving all the flower resources they need, then nesting resources, host availability (in the case of parasitoids), hibernation sites etc. can all become important. Our work did not indicate a strong one-to-one relationship between flower favorability and flower-visitor numbers. While this might, legitimately, bring our methods somewhat into question, it might also suggest the presence of other limiting factors whose identification might be an important contribution to facilitating management. Ways of exploring this might include augmenting nesting resources (e.g., bee hotels and sand piles for ground nesters) and seeing how much interest there is from the insect community – ample and rapid adoption of such resources might suggest they have, indeed, been limiting.

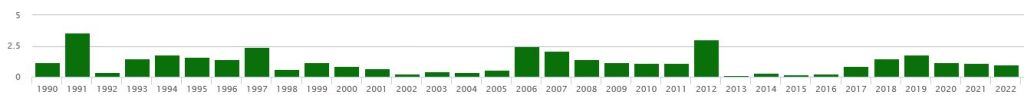

How relevant is ecological lag time? Insect populations cannot respond instantaneously to increased flower resources. Our work at Ironwood and at the Farm Hub suggest that part of what is important is what butterfly biologist Ann Swengel calls ‘consistent diversity’, that is a diversity (and abundance) of resources that persists across time. The long-term aspect is what gives insects the chance to ‘settle in and raise a family’ (or, better put, to raise families across multiple generations). In thinking about farm management, this doesn’t mean that the same flowers have to be found in the same beds year after year, but rather that the same suite of flowers, indeed same suite of habitats, needs to be found somewhere on the farm across multiple years if one is hoping to support higher/more diverse insect populations in the long run.

How important are ‘native’ and wild plants? The work reported here suggests that the different flower visitors do show distinct flower preferences, but that native vs. non-native or cultivated vs wild are not necessarily the sole, and perhaps not even the primary, determinants of those preferences. It appears that, within the very limited context of our work, both native and non-native (and cultivated and wild) flowers can make positive contributions. HOWEVER, nativeness is likely important in ways that we barely scratched with our methodology. For example, while many moths and butterflies might be relatively loose in the flowers they choose to nectar from, their leaf-eating larvae are often much more picky and native insect species are likely to favor native host plants for their young (although they sometimes grow to like naturalized non-natives too). Further, while the bee groups we studied did not, as a whole, show an overwhelming preference for native flowers, there are rare, specialized bees whose life histories are indeed closely tied to native plants. The Macropis bee we documented feeding on Fringed Loosestrife (Lysimachia ciliata) is one such example. In sum, were you able to raise only native flowers, your contribution to insect conservation would likely be higher, but non-native flowers can also make a positive contribution so long as their limitations are understood.

If we agree that augmenting the availability and diversity of favorable flowers is one (but not the only) useful way of contributing to flower-visitor abundance and diversity, then we suggest the following framework when thinking about potential “tweaks” to farm management in order to increase flower resources:

- Vibrant fencelines – How close to the fence do you need to keep things mowed and at what frequency? How to keep vines and/or invasive shrubs from overwhelming the fencelines while mowing less? Note that ‘looser’ management might not only increase flower abundance and diversity, but also expand nesting sites for those insect species seeking hollow plant stems or thatched areas for their nests. Depending on the specific situation of the farm, looser management of fencelines might however also invite the spread of invasive plants and the establishment of vegetable-raiding Groundhog colonies.

- Enrichment seeding/planting in wild areas – Several of the study farms had loosely-managed oldfields, wet meadows, or shrubby areas which, although they did provide some flower resources during a part of the growing season, have the potential to provide flowers over a longer period and/or to support more diverse and/or abundant flowers. Short of a complete conversion, which might be expensive and not even be desirable if the area already does contain good patches of flowers, one could consider tilling up small areas and seeding or planting them with desired flower species.

- Dedicated annual or perennial flower beds within the cropped area – These areas may also improve nesting/hibernation habitat (e.g., “beetle banks”), but be forewarned, such habitat can also host Groundhogs and voles!

- Reduced mowing frequency/changed timing/increased mowing height of lawns – What is the goal of the lawn mowing and how might those goals be met while at the same time providing more room for flowers?

- Reduced mowing frequency/times of lightly managed areas, such as mature field edges, old fields, wet meadows – As with fencelines, looser management can also enhance nesting/hibernation resources for insects, but potentially also facilitate invasive plants and Groundhogs.

- Welcoming the weeds – Of course, there are good reasons why this sometimes conflicts with food production, but when possible being tolerant of (or, at least, feeling less guilty about) in-bed flowering weeds might be appropriate given the how attractive some of the ‘weeds’ seemed to be for certain flower visitors.

- Editing hedgerows and margins for flowering (native?) shrubs – Hedgerow installations, while potentially valuable, can be daunting. However, the removal of less desired woody plants can provide more growing space for those you do want. While we did not include many woody plants in our surveys last year – in part because we only started them in June when most woody plants are done flowering – we know from the literature that some of them provide important early-season flower resources and could include them in expanded future surveys.

CONCLUSIONS: What are our last thoughts and yours?

These analyses have, in some ways, been a ‘proof of concept’. We can take field observations of flowers and flower visitors and convert them into farm-specific maps, but if the results seem esoteric and not useful, then it has been a wasted effort.

The most pressing conclusion is thus a question: is this sort of information useful to you? If not, then further exploration of this theme makes little sense.

However, if it does seem useful, then how could it be made more useful? Gathering more flower-visitor observations in order to refine our assessment of flower favorability might be worthwhile. No doubt some of our results are flukes caused by having relatively little data (for example, Viper’s Bugloss seems to be a winner, but we only observed it on one farm on one date). More observations, potentially from more farms, could help us understand how generally applicable our results are.

We could also refine our visual bee, wasp, and hover fly identifications. Although species-level identification may only rarely be practical, greater refinement is possible. Indeed, as the summer wore on, aided by learning eyes and diligent photography, we were able to gather somewhat more detailed ID information. From an applied perspective, such information may have only limited value unless it reveals certain closely knit relationships between, say, a bee and the pollination of a certain flower or a particular wasp who attacks a particular host. However, from the perspective of biodiversity conservation such IDs can be crucial, because it is only at this level that we will truly understand when a given farm or flower is supporting rare species.

We could also expend more effort trying to refine our understanding of the correspondence between flowers and flower visitors by looking at more flower beds on more days or at more times of day. This immediately raises practicality issues unless you want a live-in biologist on your farm. While extensive sampling might not be feasible or even desirable, we have recently collaborated with Laura Figueroa of UMass Amherst to use sound recordings to assess bee presence. This technique has the potential to give us a much more refined picture of bee use by allowing us to assess bee presence on multiple days at multiple times. Such an approach might also help us test our maps by giving us bee activity data in each survey unit (recall that our flower visitor observations were tied to flower types, not survey units) and even in wilder areas, such as adjacent forests (might we, for example, be able to document what habitats are most sought after by nesting bumble bees?).

Reviewing the data at hand, a central conclusion that we have already re-iterated several times is the idea of ‘different strokes for different folks’, that is different flower species and different flower classes (i.e., cultivated vs wild-growing, native vs non-native) are attractive to different groups of insects. These are results which could be refined if, as mentioned above, we are able to improve our visual identification of flower visitors. However, even at this general level, we hope that this conclusion helps emphasize the value of on-farm botanical diversity not only in a single year, but also across years – as some of our work has suggested, insect populations cannot instantaneously react to enhanced resources. On-farm botanical diversity is the groundwork that will support on-farm entomological diversity, which, in turn, could supply a greater diversity of agroecological services and add contribute to regional insect conservation in the region.